Why the L is Truly a Chicago Wonder

– By Tom Schaffner

A few years ago, the Chicago Tribune asked its readers to select the “Seven Wonders of Chicago” from a list of nominations the newspaper had compiled. Chicago’s elevated transit system — the L — was selected number three, just behind the Lakefront and Wrigley Field.

Not bad for a transportation system that was built in 1892 and has more liver spots and face wrinkles than your great grandparents.

Chicago’s L is more than just a public transportation system that efficiently moves people throughout the city. It’s an iconic symbol of Chicago, an elevated railway that has rattled and clattered unabashedly into the hearts and minds of locals and visitors worldwide for well over a century.

Because the L is so ingrained in the everyday fabric of our being, we have put together a list of interesting facts and tidbits that reinforce the idea that our rapid transit system is indeed a true wonder of Chicago.

1. Wrigley Flag Communication

In 1937, the Chicago Cubs renovated their scoreboard and decided to incorporate a system for communicating the day’s baseball results to L riders who were whizzing past the ballpark on a train. If a light-colored flag with a “W” flew, the Cubs had won the game that day; if a darker flag with an “L” was at the top of the staff, it meant the Cubs had lost another one. The flags are still in use today although they have become largely ceremonial, thanks to smartphones and other communication devices.

2. A Double Double-header

Chicago is one of the few cities in the word that has rail service to two major airports — O’Hare Field (Blue Line) and Midway Airport (Orange Line). Similarly, the CTA’s Red Line connects both of the city’s major league baseball stadiums — Wrigley Field for the Cubs (Addison Street stop) and Guaranteed Rate Field for the White Sox (35th Street stop). If these teams ever meet in the World Series, it won’t be a subway series, it’ll be a Red Line Series, two teams separated by 13 L stops.

3. Another Reason We’re the Second City

With 1,492 rail cars operating on eight routes and carrying an average of 752,734 passengers each weekday (239 million passengers per year), Chicago’s rapid transit system is the second-largest and second-busiest mass transit system in the U.S. Only the New York City transit system is larger and busier.

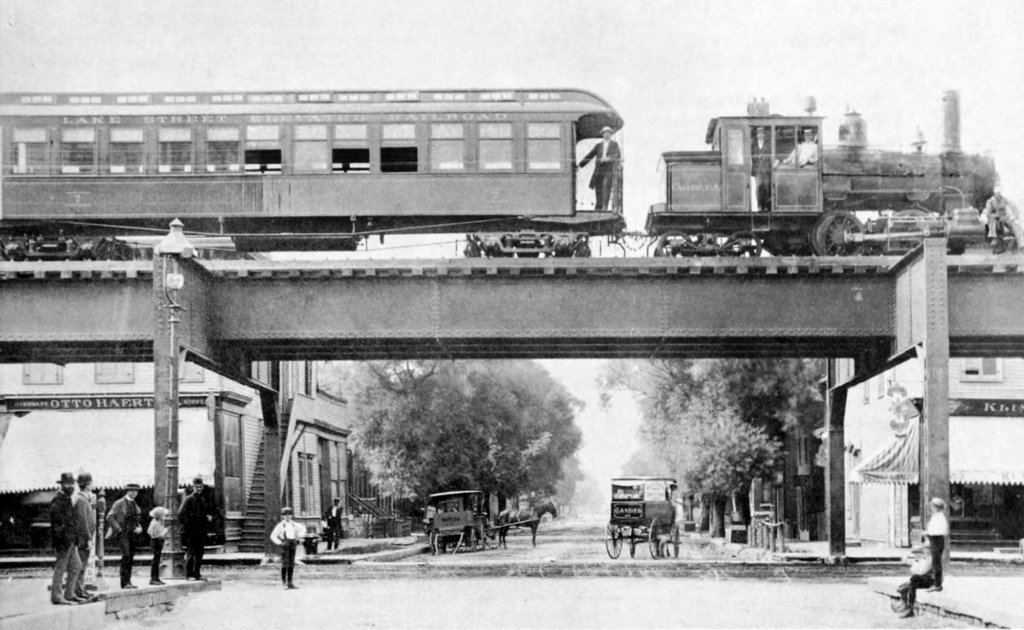

4. Not Much to Look at But Fast

On May 1892, Chicago’s first elevated train, four wooden coaches pulled by a steam locomotive, took its inaugural trip down the Southside Rapid Transit Railroad Company’s “Alley L” from Congress St. to 39th. Chicagoans thought the elevated structure was unsightly, but they liked its speed — 34 blocks in just over nine minutes.

5. How Downtown Got Its Name

Downtown Chicago is called the Loop because the elevated tracks create a loop around a rectangle formed by Lake Street (north), Wabash Avenue (east), Van Buren Street (south), and Wells Street (west). The looped track structure was created when four independently owned transit companies decided to cooperate with one another in simplifying the delivery of passengers to downtown Chicago. What they created was called the “Union Loop.” This simple invention created a legendary moniker for the city that is now known worldwide.

6. Win, Place, Show

As of 2018, the Red, Blue, and Brown Lines were the busiest train lines in Chicago, with the Red Line carrying over 225,000 passengers on an average weekday, the Blue Line with nearly 150,000, and the Brown Line with approximately 40,000 daily passengers. While ridership has been recovering since recent disruptions, it has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. While ridership is bouncing back, it still hasn’t quite reached pre-pandemic levels. Even so, these lines are still the heart of the city’s transit system, getting people where they need to go every day.

Oscar-Worthy Performances

Because nothing screams “Chicago” like an L train passing skyscrapers in the Loop, the L has been featured prominently in a number of motion pictures and television shows, including Shameless, The Blues Brothers, Risky Business, and Planes, Trains and Automobiles.

The Future is Now

Constantly changing demographics throughout the metropolitan area make it necessary for CTA officials to stay ahead of the curve and invest in tomorrow’s successful projects today. Among the projects currently underway are an expansion of the Red Line to 130th Street, station modernization and speed improvements along the Blue Line, capacity increases on the Brown Line (longer train platforms for longer trains) and a recent announcement that the City hopes to build a high speed transit system (100 m.p.h) in a tunnel between the Loop and O’Hare Airport.

As our name implies, L Stop Tours uses the L Train for all of our full tours. To fully experience the L Train, consider booking one of our tours today!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the most frequently asked questions about the L and want to learn more about the city and its history, then consider signing up for our blog newsletter!

I spend a lot of time on the L.

Our tour company, L Stop Tours, utilizes Chicago’s elevated transit system to visit unique, culturally-diverse neighborhoods throughout the city. On every tour, we tell our guests as much as we can about the L — how it came to be, the size and reach of the system, how it has evolved over time, and so on — but our guests always seem to have more questions. Like many people, they are fascinated by the L and want to know more.

Below is a list of the most frequently asked questions we receive about the L:

How big is Chicago’s rapid transit system?

With 1,492 rail cars operating on eight routes, 224 miles of track, and nearly 230 million passengers transported per year (pre-pandemic), Chicago’s rapid transit system is the second-largest and second busiest system in the U.S. The most heavily-traveled route on the system is the Red Line, which carries 252,000 passengers on an average weekday (pre-pandemic). Another interesting fact, Chicago is the only major U.S. city to have an elevated system serving its downtown area.

How old is Chicago’s L?

The city’s first elevated rail line, constructed by the privately-owned Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad, began transporting passengers on June 6, 1892, on a four-mile stretch of track between Congress Avenue just south of downtown and 39th St. The service, a small steam locomotive that pulled four wooden nuecoaches, was an immediate hit with locals and was extended another four miles the following year to accommodate visitors attending the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Jackson Park. Three other privately-owned elevated transit lines were built in the next three years — the Lake Street Elevated Railroad, the Metropolitan West Side Railroad and the Northwestern Elevated Railroad.

When did the L system go electric?

In 1895, the Metropolitan West Side elevated line was the third L company to begin rapid transit operations in Chicago but the first to use electricity to power its trains. Two years later, the South Side L introduced multiple-unit control in which the operator can control all motorized cars in a train, not just the lead car. Shortly thereafter, the remainder of the lines switched to electric service. Interestingly, electricity and multiple-unit control remain standard features on most of the world’s current rapid transit systems.

How did Chicago’s Loop get its name?

When Chicago’s first elevated lines went into operation, none were allowed to provide service in the downtown area — property owners felt the system was ugly and that it would reduce property values. A wealthy financier, Charles Tyson Yerkes, thought otherwise and was able to convince property owners that an elevated transit system would bring more people downtown and would be good for business. Finally, the property owners agreed and Yerkes built what he called the “Union Loop,” a 1.79-mile closed circle that connected all of the city’s privately-owned elevated railroads into a common system. Over the years, the term “Loop” has come to refer to Chicago’s original downtown area, or more precisely, any property that is located inside the Loop elevated structure (an area bounded by Lake Street on the north, Wabash Avenue on the east, Van Buren Street on the south and Wells Street on the west).

Why did Chicago decide to elevate its transit system while other cities used subways?

Chicago’s resolve to rebuild itself after the Great Chicago Fire resulted in an unprecedented period of growth and expansion for the city — between 1872 and 1900, Chicago was one of the fastest growing cities in the world. As a result, pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages and streetcars converged to create gridlock on downtown streets — city fathers knew that a new transit system was badly needed. Although subways were the choice in other growing cities like New York and London, Chicago selected elevated railways because they were cheaper to construct and did not require much digging (there were concerns at the time that the city’s swampy soil might not tolerate a subway system).

When and why did the Chicago Transit Authority come into existence?

In 1924, all of Chicago’s original L companies were combined into a new private entity, the Chicago Rapid Transit Company, in order to facilitate better cooperation among the lines. Following World War II, Chicago and Illinois officials decided that all bus, streetcar and rapid transit lines should become publicly-owned. In 1947, the newly established Chicago Transit Authority assumed control of all transportation systems within the City of Chicago.

Chicago built two subways, not elevated lines, many years after the elevated system was well established. Why?

The State Street subway, a 5-mile segment in the middle of today’s Red Line, went into operation in 1943 and the Dearborn Street subway, serving the Blue Line downtown, was completed in 1951 Both of these service expansions were built as subways in order to minimize train traffic on the Loop tracks and to speed passenger travel through the downtown area. To this day, trains on the Red and Blue lines descend from elevated tracks just outside the Loop into the subways in the downtown area (35 feet below ground), make several stops, and ascend to elevated tracks after emerging from the downtown subway.

Why are there no public restrooms at CTA stations?

The CTA used to have public restrooms at most stations but closed them in the 1970s. (These restrooms are now locked and available only to CTA employees and/or passengers with an emergency medical condition.) The reason? According to the CTA, public restrooms require significant resources to maintain and keep secure — and the CTA does not have the resources to maintain these facilities or keep them secure at a high enough level for the general public.

Does the CTA ever use old rail cars for regular service?

Not for daily or regular service, however, the CTA maintains a small fleet of vintage rail cars, the Heritage Fleet, that is used for charters or special events in which the public is invited. Additionally, Chicago L car number one — the very first car used on the L tracks (1892) — is on permanent display at the Chicago History Museum. Visitors to the museum are invited to step aboard the car and look around.

Is it the “L” or “el?”

Both the CTA and the four original privately-owned transit companies always referred to their trains as the “L,” meaning that the nickname (short for elevated railway) dates back nearly 130 years. It is thought that rapid transit operators in Chicago preferred “L” because it was different from elevated service in New York City. which went by the nickname “the el.”

Why are Chicago’s rapid transit cars shorter than those in other cities?

Chicago’s transit vehicles are shorter in order to better navigate the sharp turns in the Loop, such as Adams and Wabash and Wells and Van Buren. And while Chicago’s rapid transit system is the second busiest in the United States, its shorter cars (48 feet versus New York’s 51 feet) comfortably handle its ridership loads on a daily basis. In short, there is not a need for longer cars.

How much is a single ride on the L?

A single-ride train ticket — three rides within two hours of purchase — costs $3 (or $5 if purchased at O’Hare Airport). Riders can also utilize the CTA’s electronic fare program, Ventra, which offers a number of different fare and pass options that can be loaded onto the reusable card, as well as a cash balance or electronic payment options.

Are there any express trains on the CTA system?

The only scheduled express train service on today’s CTA system is the Purple Line, which skips a few stops on its way to and from Howard Street and the Merchandise Mart, cutting about 15 minutes off the normal 45-minute all-stop service one would encounter by taking Red and Brown Lines to either of these destinations. Years ago, the CTA utilized a skip-stop service on all of its routes (“A” and “B” trains that stopped at alternate “A” and “B” stops in order to speed transit times), but that service was eliminated in 1995.

Any expansion of the system planned for the future?

The Chicago Transit Authority is proposing to extend the Red Line from the existing terminal at 95th/Dan Ryan to 130th Street, subject to the availability of funding. The proposed 5.6-mile extension would include four new stations near 103rd Street, 111th Street, Michigan Avenue, and 130th Street.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

What’s your preferred mode of transportation for moving about Chicago?

Bus? Scooter? Divvy bike? Cab? Shared ride? Walking? Your car? Pedicab? Horse-drawn carriage? But you better hurry — horse-drawn carriages become illegal in Chicago on January 1, 2021.

For many years — more than I can remember — I’ve used the CTA’s rapid transit system (the “L”) as my primary conveyance throughout the metropolitan area. The Chicago transit system is convenient, affordable, punctual (usually), offers unique and scenic views, takes you to interesting neighborhoods and, frankly, is just plain fun to ride. Chicago’s L is iconic — when you ride the rails here, you’re taking a trip on a Chicago transit system that’s 128 years old (and counting). It’s a one-of-a-kind experience — something that is unduplicated in the world of transportation.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, I’ve gone more than three months without taking the Chicago transit system anywhere. Not because I was afraid, I didn’t want to occupy a space that otherwise could have been used by an essential worker that needed to get to their job with as little disruption from outsiders as possible.

Reopening

Now that summer has arrived and the pandemic in Chicago and throughout Illinois seems to be a bit more under control (declining cases and hospitalizations, lower overall positivity rate from tests), the city and state are in the process of reopening, which means that offices, restaurants, retail stores, cultural institutions, parks and the lakefront are now emerging from their multi-month lockdown (albeit with reduced capacity levels and plenty of social distancing). Nevertheless, they are open and as progress continues to be made locally with respect to the pandemic, things are beginning to return to normal.

The Chicago transit system is undergoing a similar transformation. During the early days of the pandemic, ridership on the L was down almost 90 percent (from normal operations). The trains were virtually empty, often no one riding them at all. But as Chicago and Illinois began to “flatten the curve” of Covid-19 cases throughout the region, the CTA turned its efforts toward sanitizing, disinfection and ways to restructure the Chicago transit system so that crowds could be minimized and there would be plenty of room for social distancing. In other words, they began the process of making the Chicago transit system safer to ride while we’re still in the pandemic.

They’ve done a tremendous job. On one of my recent L trips, everything was clean, the train wasn’t crowded and social distancing wasn’t a problem. I sat in a row of seats in the middle of the car by myself, the nearest other passengers were evenly spread throughout the car. All passengers were wearing masks and the car was marked with decals indicating safe places to stand or sit.

The CTA has been working on a number of improvements to its system during the pandemic:

- The CTA has adopted a new cleaning regimen that is among the most rigorous of any transit system in the nation. All Chicago transit system cars are thoroughly cleaned before entering service and high touch surfaces in railcars and stations are cleaned several times a day.

- New technologies, including electrostatic sprayers and antimicrobial coatings, are also being used to further enhance cleaning and disinfection.

- All Chicago transit system passengers are required to wear face masks while riding trains.

- Cars on trains are now limited to no more than 22 passengers to achieve proper social distancing standards. This is accomplished with staggered seating and marked places to stand on each train.

- When conditions dictate, the CTA runs longer and more frequent trains to keep passenger counts lower and at more manageable levels.

- Decals have been placed on station floors and platforms to guide passengers where to stand and how to keep distanced from one another. All Chicago transit system rail stations are cleaned daily and are regularly power-washed.

- The CTA has been working with the business community to encourage companies and organizations to stagger employee starting and ending times in order to help minimize crowding on trains.

Positive Reviews

Early reviews on the CTA’s efforts to re-attract customers to its system have been very positive. A recent article in the Chicago Tribune gushed about the transit agency’s efforts. “Spacious! Clean! Is this the CTA? Even better, everyone is wearing a mask, not just the crazy people.”

Seems like the time is right to get out and enjoy Chicago.

For more information on the CTA’s efforts to clean, disinfect and socially distance its system, go to transitchicago.com/coronavirus.

And if you’re interested in using the CTA line to explore Chicago, consider going on one of L Stop’s Chicago walking tours!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the best parks in Chicago, then consider signing up for our blog newsletter!

With more than 600 parks comprising 8,800 acres of green space, the Chicago Park District is the largest municipal park manager in the nation. It also is responsible for 28 indoor pools, 50 outdoor pools, and 26 miles of lakefront including 23 swimming beaches and one inland beach.

The city’s park system is also convenient. A recent study found that 98 percent of all city residents live within a 10-minute walk — or roughly half a mile — of a public park. In other words, serenity is not very far away.

Since we offer Chicago walking tours that utilize the L to visit neighborhoods throughout the city and suburbs, we’ve compiled a list of our favorite neighborhood parks that are also easily accessible via the L.

Best Parks in Chicago With Easy Access to the L

- Ping Tom Memorial Park (Via Green Line)

- Garfield Park (via Red Line)

- Wicker Park (Via Blue Line)

- Douglas Park (Via Pink Line)

- Grant Park (Via Any Line Except Yellow)

- Gillson Park (Via Purple Line)

- Humboldt Park (Via Blue Line)

- Oz Park (Via Brown Line)

1. Ping Tom Memorial Park (Via Red Line)

This beautiful 17.24-acre park is located on the south bank of the Chicago River, a few blocks from the Cermak-Chinatown stop on the CTA’s Red Line and, of course, the Chinatown neighborhood (which you see more of on our Chicago Chinatown Food Tour.). Named for Ping Tom, a prominent Chinatown businessman and civic leader, the park was created in October 1999 and features a pagoda-style pavilion, bamboo gardens and a playground. In warmer weather, the Chicago Water Taxi makes scheduled stops at Ping Tom Park from various downtown locations.

2. Garfield Park (Via Green Line)

Only steps from the Green Line, Garfield Park is a 184-acre green space that was designed by William LeBaron Jenney, architect of the world’s first skyscraper (Chicago’s Home Insurance Building). It is the oldest of the city’s three original West Side Parks, which include Humboldt Park and Douglas Park. The centerpiece of the park is the 4.5-acre Garfield Park Conservatory, one of the largest greenhouse conservatories in the United States. Open year-round, the conservatory is particularly enticing in the middle of winter when it offers visitors an escape from the white snow into a world of green. You can experience the Garfield Park Conservatory during our Fulton Market tour!

3. Wicker Park (Via Blue Line)

Though only four acres, Wicker Park is a much-beloved and widely-used community park in the heart of one of Chicago’s toniest neighborhoods. Located only steps from the Blue Line L stop at Damen, Wicker Park is dog-friendly and includes baseball diamonds, a walking path, a spray pool and a water playground for children and a statue of Charles Wicker, who, with his brother Joel, donated the park to the community in hopes that it would one day spur development within the community. It did, perhaps well beyond even the wildest dreams of the Wicker brothers.

4. Douglas Park (Via Pink Line)

A short walk from the Pink Line station at California is Douglas Park, named in honor of Stephen A. Douglas, a U.S. Senator from Illinois who lost the 1860 presidential race to Abraham Lincoln, also from Illinois. Spanning 173 acres and straddling a few neighborhoods on the city’s West Side (Pilsen and North Lawndale), Douglas Park was built for recreation. It currently houses a miniature golf course, five playgrounds, an outdoor swimming pool, soccer fields, basketball courts and an oval running track. It also features a beautiful lagoon, a wide variety of trees, and an old stone bridge. You can see more of what the Pink Line offers on our Pilsen Chicago Neighborhood tour!

5. Grant Park (Via Any Line Except Yellow)

Also proudly referred to as “Chicago’s Front Yard,” Grant Park is one of the city’s largest green spaces, stretching from Randolph St. on the north to the Museum Campus on the south, Michigan Ave. on the west and Lake Michigan on the east. In addition to baseball diamonds, soccer fields, tennis courts and breathtaking gardens, Grant Park also hosts innumerable food and music festivals and other special events throughout the year. Also part of the greater Grant Park area are Millennium Park, Maggie Daley Park, Buckingham Fountain, The Art Institute, The Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, Adler Planetarium and two leisure boat harbors. The 313-acre park, one of the largest in the city, can be accessed by any L (except the Yellow Line) at stations throughout the Loop.

6. Gillson Park (Via Purple Line)

Located in the nearby suburb of Wilmette, Gillson Park is a half-mile walk from the Linden Avenue stop on the CTA’s Purple Line. This beautiful 60-acre park is located on the shore of Lake Michigan and features a public beach, picnic facilities, sailboat and kayak rentals, bicycling, soccer tennis and a wide variety of other recreational activities. Named for the first president of the Wilmette Park District’s Board of Commissioners, Louis K. Gillson, the park opened to the public in 1910.

7. Humboldt Park (Via Blue Line)

Humboldt Park is a 207-acre park on the West Side of Chicago that is located in a community of the same name. The park was named for Alexander von Humboldt, a well-known geographer and naturalist in the mid-1800s. The park features three major historical public buildings, including the Boat House (now a café overlooking the lagoon); the Field House, which includes a fitness center, two gymnasiums, meeting rooms and an inland beach; and the historic Humboldt Park Stables, which is in the process of being converted to the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture. Humboldt Park is a 20-minute walk from the Blue Line Damen Ave. stop.

8. Oz Park (Via Brown Line)

Located in the Lincoln Park neighborhood, Oz Park takes its name from a novel written by Lyman Frank Baum, a former resident of the neighborhood who wrote “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” The 13-acre park features sculptures of characters from the novel, The Tin Man, the Cowardly Lion, the Scarecrow and Dorothy and Toto. “The Emerald Garden,” located at the northeast corner of the park, has a path of flowers that visitors can walk through; nearby is “Dorothy’s Play Lot,” which includes swings and climbing equipment for children. Oz Park is located a few blocks from the Brown Line Armitage stop. You can see more of what the Brown Line has to offer on our Historic Pub Tour.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Learn more about the Bloomingdale Trail (the 606) and its history in Chicago.

The Bloomingdale Trail

We generally use this space to write about Chicago’s elevated transit system, the “L.” Our business, L Stop Tours, is all about the L and the 77 city neighborhoods it passes through. Today we’re going in a slightly different direction and writing about a different elevated railroad system, the Bloomingdale Trail and its larger park-encompassing cousin, the 606.

The Bloomingdale Trail is a former elevated railway line that the City of Chicago converted into an elevated greenway in 2015. It runs west from Ashland Avenue (along W. Bloomingdale Avenue) to Ridgeway Avenue (3732 west). At 2.7 miles in length, the Bloomingdale Trail is the second longest greenway project of a former elevated rail line in the world, trailing only the Promenade Plantée in Paris (2.9 miles in length). Today the only traffic on the Bloomingdale Trail are hikers, bikers, joggers and pedestrians of all shapes and sizes.

Originally constructed in 1873 by the Chicago and Pacific Railroad Company as part of a 36-mile link to Elgin, Illinois, the railroad was built at street level and carried both passenger and freight traffic. In the 1910s the railroad was elevated approximately 20 feet when as ordinance designed to reduce pedestrian fatalities at street level was passed by the City of Chicago. As businesses began to move out of the area (such as Schwinn Bicycle Company), freight traffic on the rail line began a long, steady decline into irrelevancy. The last freight train ran on the line in 2001.

Though the City of Chicago had investigated converting the Bloomingdale Line into a greenway as early as 1997, it wasn’t until 2004 that the project was revisited and made part of the Logan Square Open Space Plan, which prosed a linear park with public access ramps every few blocks. Groundbreaking for the project occurred on August 27, 2013. In addition to extensive landscaping and access ramps, the trail consists of a 10-foot wide paved path with a 2-foot soft shoulder on either side.

The Bloomingdale Trail is central to a larger series of parks and a trail network in the area called “The 606,” which derives its name from the first three digits of all Chicago ZIP Codes. The intent is to symbolize the linkage between parks and the neighborhoods they serve, as opposed to the elevated rail line which served to isolate and “wall off” neighborhoods. The four newly-linked neighborhoods are Wicker Park, Bucktown, Humboldt Park and Logan Square.

Access to the Bloomindale Trail via public transportation from downtown is easy — take the CTA Blue Line to either Damen or Western Avenues.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

With 78 neighborhoods stretched over 234 square miles, Chicago needs an efficient and reliable transportation system to move people from one destination to another. That’s where our city’s extensive rapid transit system (the various CTA train lines) comes in.

Over the past 125 years, Chicago’s elevated railway has grown from a single line — the “Alley L” which transported passengers from Congress Street to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition on the South Side — to eight lines that fan out across the metropolitan area like spokes on a bicycle wheel. The 102–mile system, which is the second largest and second busiest in the United States, boards approximately 720,00 riders every weekday morning and provides transportation services to more than 235 million riders annually,

The system that exists today, however, is not the system of days gone by. Over the years, the Chicago Transit Authority has abandoned and ultimately demolished seven entire lines and branches since it took control of the system in 1947. These CTA train lines were eliminated because they were underutilized or were redundant to other forms of transportation, such as bus routes, streetcars or newly-constructed expressways.

CTA train lines that are discontinued and demolished since 1947

Logan Square Line

Before the construction of the Milwaukee-Dearborn Street subway (1951), an elevated line headed west from the Loop to Paulina then jogged north to Milwaukee Ave. The line then traveled north to Logan Square where it terminated above a newsstand near Kedzie and Logan Blvd. The line opened for business on May 6, 1895. Years later, after the subway was built, it provided the Logan Square Line with a more direct route to the Loop. Once this connection was made, it rendered the Paulina portion of the line obsolete and unnecessary. It was abandoned and demolished in 1964.

Humboldt Park Branch

From 1895 until 1954, an elevated line connected Wicker Park and the north side of Humboldt Park. Consisting of only six stations, the branch proceeded west on a right of way that paralleled North Avenue and terminated at Lawndale Avenue. A huge decline in ridership was the primary reason for ceasing operation — in 1910 the lined averaged 12,550 passengers per day but by 1951 it only carried 1,250 passengers per day. The branch was abandoned on May 4, 1952.

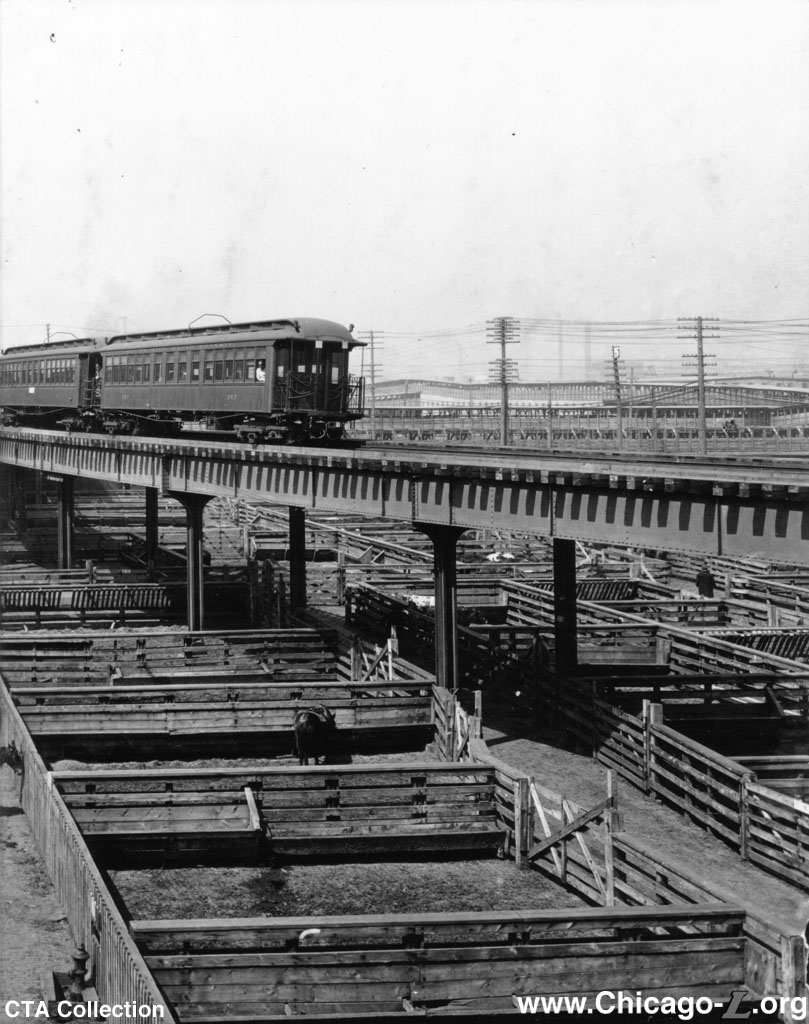

Stock Yards Branch

Built in 1908, this elevated branch ran west from the main South Side Line (Green Line) at Indiana and continued for 2.9 miles, serving eight stations along the way. When it reached the Union Stock Yards, it made a counterclockwise loop, stopping at three huge meatpacking plants— Morris & Company, Swift & Company and Armour & Company. When the Stock Yards began to decline in importance in the 1930s, the line lost ridership and, ultimately, was abandoned on October 6, 1957. The CTA replaced the L with the #43 bus line, which followed the exact same route into the Yards. The move to close the line was precipitous — the Stock Yards itself closed in 1971.

Kenwood Branch

This line, six stations and 1.25 miles in length went into service September 20, 1907. It separated from the main South Line (Green Line) at Indiana Ave. and proceeded eastbound to 42nd Place (near Lake Shore Drive). When ridership on the nearby Stock Yards Line began to decline in the 1930s, the Kenwood line began to decline, as well. The Kenwood line also was costly to maintain and had equipment and infrastructure (stations) that were in poor condition. The CTA shut the branch down on Nov. 30, 1957.

Westchester Branch

Westchester Branch

Serving nine stations in Chicago’s western suburbs, the Westchester Branch was 5.5 miles in length and opened with great fanfare on September, 30, 1926. It ran north from Mannheim and 22nd (Westchester) to Roosevelt Road where it then turned east (passing through Bellwood and Maywood) and continued all the way to Desplaines Ave. (Oak Park). Built to capitalize on the future growth of Westchester as a suburb, the line was a little ahead of its time. It closed in 1951 due to a lack of riders. Ironically, Westchester began to experience significant growth only a few years after the line was abandoned by the CTA.

Normal Park Branch

Less than a mile long, the Normal Park Branch ran from the main South Line (Green Line) in Englewood at Harvard St. south to 69th St, serving four stations along the way. It opened on May 25, 1907 but it never attracted many passengers. By late 1953 it was generating less than 100 fares a day, barely enough for a bus line but not for rapid transit service. The CTA shut down the line on Jan. 29, 1954.

Garfield Park Line

Garfield Park Line

Opened in 1895, the Garfield Park Line ran from the Wells Street Terminal in the Loop (Wells and Quincy) paralleling Van Buren and Congress all the way to the western edge of the city (Cicero Ave.) and, eventually, to the near west suburbs (Oak Park, Bellwood, Maywood). When the Congress Expressway (Eisenhower) was under construction in the mid 1950s, the 50-plus year Garfield Park Line was demolished in favor of a new rail line (Blue Line) that would occupy the median of the new expressway.

For a fun CTA train experience and to see what remains of the old lines, consider booking a Chicago walking tour with L Stop Tours!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.