The Most Notorious Party Ever — Chicago’s First Ward Ball

– By Tom Schaffner

It’s December in Chicago and it’s time to celebrate. Not Christmas, it’s time for the annual First Ward Ball — the most raucous, hedonistic, booze-soaked party for gamblers, pimps, prostitutes, pickpockets, police captains and politicians that the world has ever seen.

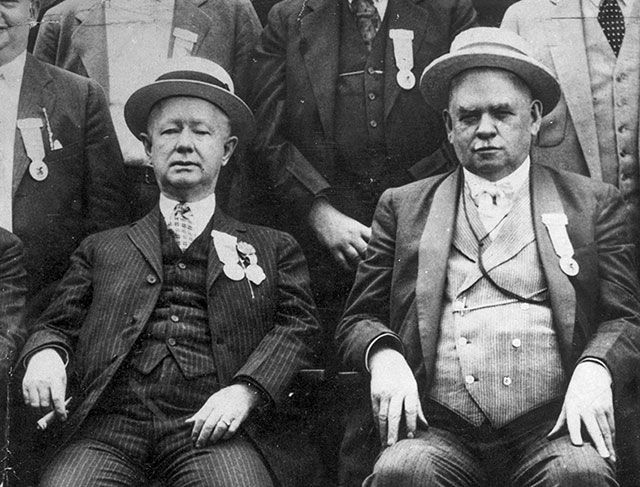

Hinky Dink and Bathhouse

We take you back to December 1897 when Chicago had not one but two elected aldermen to serve each ward. Representing the city’s First Ward were two gentlemen with perhaps the greatest nicknames of all time, John “Bathhouse” Coughlin, a burly, boisterous man who worked in — and owned — several bathhouses throughout the city and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, a quiet, teetotaling saloon owner who received his moniker from Joseph Medill, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, simply for being 5 feet 4 inches tall.

As emperors of the First Ward, Coughlin and Kenna presided over the Levee, Chicago’s infamous red light district just south of the Loop along the South Branch of the Chicago River. Throughout the year, Coughlin and Kenna used their positions of authority to extract monetary and political support from the hustlers, pimps, gamblers, prostitutes and saloon keepers who comprised the Levee. They then used this money and political support to consolidate their positions as undisputed “Lords of the Levee.” Political corruption of the first order.

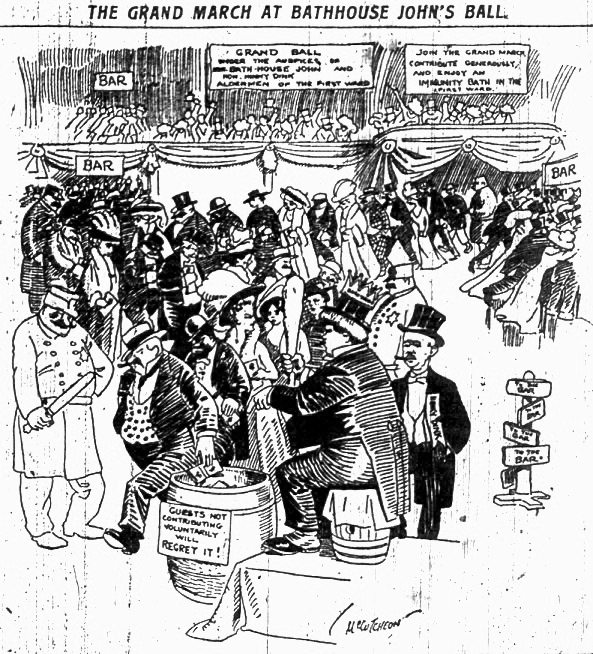

One of the ways Coughlin and Kenna were able to “raise funds” on an annual basis was by hosting an event called the First Ward Ball, a wild evening of debauchery and bacchanalia that, according to some revelers, was an orgy of vice. The first event, held in 1896 at the 7th Regiment Armory on South Wentworth Avenue, attracted a wild mix of society thrill seekers, police captains, politicians, prostitutes and gamblers. It was wildly successful. According to one newspaper report:

“Brewers, wine merchants and distillers offered supplies of liquor at discount prices. Waiters, anticipating huge tips, eagerly paid $5 each for the right to serve at the event. Policemen and politicians came and mingled with pickpockets and common criminals. Prostitutes, in scanty but expensive costume gowns, arrived with police escorts. At the stroke of midnight Coughlin — attired in a green dress suit, mauve vest, pale pink gloves, yellow pumps and silken top hat and flanked by Minna and Ada Everleigh, the brothel queens —led the ball`s grand march.”

Big and Bad

Every year the First Ward Ball grew larger and wilder. By 1908, the First Ward Ball featured 20,000 paying guests and had moved into the spacious Chicago Coliseum, a venue that normally hosted national political conventions and championship boxing matches. During the course of the evening, revelers downed 10,000 quarts of champagne and 30,000 quarts of beer. Riotous drunks stripped off the costumes of unattended young women. A madam named French Annie stabbed her boyfriend with a hatpin.

Kenna beamed with joy. “It’s a lollapalooza! There are more people here than ever before. All the business houses are here, all the big people. Chicago ain’t no sissy town.”

Indeed it wasn’t. However, by 1909, the reformers had had enough. “A real description of last year’s ball is simply unprintable,” said Arthur Burrage Farwell, the president of the Chicago Law and Order League. “We must stop this disgrace.”

Sustained public pressure prompted Chicago Mayor Fred Busse to put an end to the soiree and on December 10, 1909 the city revoked the liquor license and the First Ward Ball was no more.

This December when you’re out and about with family and friends, hoisting a cocktail and enjoying a little holiday merriment, remember to toast Bathhouse Coughlin and Hinky Dink Kenna — two corrupt machine politicians who put the “Party” in Democratic Party.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

The invention of baseball is murky. Was it created by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York, or, was it Alexander Cartwright, a volunteer firefighter and bank clerk in New York City who codified a set of rules that would form the basis for modern baseball? Adding to the controversy is evidence that early forms of baseball were played in the years just following the American Revolution, several decades before Doubleday or Cartwright were even on the scene.

But Who Invented Softball?

There is no debate about who invented softball, however. The game was invented in 1887 on Thanksgiving Day in Chicago.

How it all Started

The story of its invention is compelling. A group of men gathered at Chicago’s Farragut Boat Club to learn the result of that day’s Harvard versus Yale college football game. When Yale was announced as the winner, a Yale alumnus wadded up a boxing glove with the string ties and playfully threw it at a Harvard supporter. The Harvard supporter swung at the glove with a broom handle and the rest of the group looked on with interest. George Hancock, a reporter for the Chicago Board of Trade jokingly called out, “Play ball,” and the first game of “softball” began in earnest. According to reports, 80 runs were scored during that initial match and the final score was 41-40.

Yellow softball on pitchers mound

By 1895, the game had moved outdoors, a complete rulebook had been issued and players had developed new names for the sport — “kitten ball,” “diamond ball,” “mush ball,” and “pumpkin ball.” It wasn’t until 1926 that the term softball was first used. Prior to this date, the size of the ball had varied considerably, depending mainly on where the game was played. Most of the world adopted a 12-inch ball and played the game with gloves. In Chicago, where the sport was born, the game moved forward with a 16-inch ball — and no gloves were allowed. The reason for the popularity of the sport in Chicago was because a bigger, softer ball meant that it could be played on smaller city “fields,” such as a cramped playground, someone’s back yard and even inside a gymnasium, if necessary.

The 16-inch game became incredibly popular nationwide when the first-ever national amateur softball tournament was held in conjunction with Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933.

The Strategy of Softball

In addition to no playing with gloves, the 16-inch game is different from other versions of softball in several respects. As the game progresses, the 16-inch ball gets softer, making it more difficult to hit great distances. Teams and batters must alter their offensive strategies as the game moves into the late innings. Throwing and catching the ball also requires players to utilize different techniques. Fielders will often bounce the ball to their throwing target to make it easier to complete the play. Others who are looking to catch the ball will often let the ball hit their chest first before trapping the ball with their hands and fingers.

Like golf, the sport of softball has seen a precipitous decline in participation during the last several decades. Youth have gravitated to other sports and Baby Boomers — one-time stalwarts of the sport — are aging and playing less. And while it is rare indeed to see a pick-up softball game being played in fields or open spaces around the city (as there used to be), there are still a number of city and suburban leagues where those who are interested can get involved.

So whether you play 12-inch, 16-inch or women’s fast pitch, remember that the game was invented here by a group of football fans who improvised a “ball” with a boxing glove.

Only in Chicago.

If you thought Chicago’s history with softball is interesting, then considering booking one of L Stop’s Chicago tours. Our tours are filled with interesting Chicago history facts that you won’t get from other tours.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

With 78 neighborhoods stretched over 234 square miles, Chicago needs an efficient and reliable transportation system to move people from one destination to another. That’s where our city’s extensive rapid transit system (the various CTA train lines) comes in.

Over the past 125 years, Chicago’s elevated railway has grown from a single line — the “Alley L” which transported passengers from Congress Street to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition on the South Side — to eight lines that fan out across the metropolitan area like spokes on a bicycle wheel. The 102–mile system, which is the second largest and second busiest in the United States, boards approximately 720,00 riders every weekday morning and provides transportation services to more than 235 million riders annually,

The system that exists today, however, is not the system of days gone by. Over the years, the Chicago Transit Authority has abandoned and ultimately demolished seven entire lines and branches since it took control of the system in 1947. These CTA train lines were eliminated because they were underutilized or were redundant to other forms of transportation, such as bus routes, streetcars or newly-constructed expressways.

CTA train lines that are discontinued and demolished since 1947

Logan Square Line

Before the construction of the Milwaukee-Dearborn Street subway (1951), an elevated line headed west from the Loop to Paulina then jogged north to Milwaukee Ave. The line then traveled north to Logan Square where it terminated above a newsstand near Kedzie and Logan Blvd. The line opened for business on May 6, 1895. Years later, after the subway was built, it provided the Logan Square Line with a more direct route to the Loop. Once this connection was made, it rendered the Paulina portion of the line obsolete and unnecessary. It was abandoned and demolished in 1964.

Humboldt Park Branch

From 1895 until 1954, an elevated line connected Wicker Park and the north side of Humboldt Park. Consisting of only six stations, the branch proceeded west on a right of way that paralleled North Avenue and terminated at Lawndale Avenue. A huge decline in ridership was the primary reason for ceasing operation — in 1910 the lined averaged 12,550 passengers per day but by 1951 it only carried 1,250 passengers per day. The branch was abandoned on May 4, 1952.

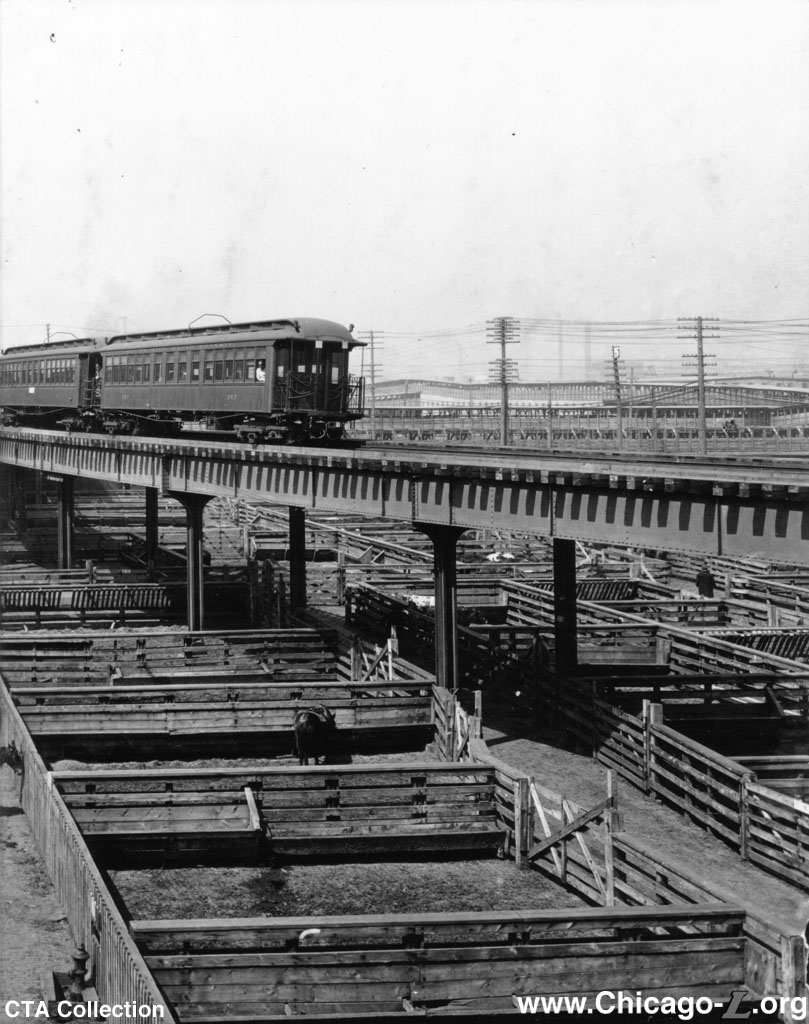

Stock Yards Branch

Built in 1908, this elevated branch ran west from the main South Side Line (Green Line) at Indiana and continued for 2.9 miles, serving eight stations along the way. When it reached the Union Stock Yards, it made a counterclockwise loop, stopping at three huge meatpacking plants— Morris & Company, Swift & Company and Armour & Company. When the Stock Yards began to decline in importance in the 1930s, the line lost ridership and, ultimately, was abandoned on October 6, 1957. The CTA replaced the L with the #43 bus line, which followed the exact same route into the Yards. The move to close the line was precipitous — the Stock Yards itself closed in 1971.

Kenwood Branch

This line, six stations and 1.25 miles in length went into service September 20, 1907. It separated from the main South Line (Green Line) at Indiana Ave. and proceeded eastbound to 42nd Place (near Lake Shore Drive). When ridership on the nearby Stock Yards Line began to decline in the 1930s, the Kenwood line began to decline, as well. The Kenwood line also was costly to maintain and had equipment and infrastructure (stations) that were in poor condition. The CTA shut the branch down on Nov. 30, 1957.

Westchester Branch

Westchester Branch

Serving nine stations in Chicago’s western suburbs, the Westchester Branch was 5.5 miles in length and opened with great fanfare on September, 30, 1926. It ran north from Mannheim and 22nd (Westchester) to Roosevelt Road where it then turned east (passing through Bellwood and Maywood) and continued all the way to Desplaines Ave. (Oak Park). Built to capitalize on the future growth of Westchester as a suburb, the line was a little ahead of its time. It closed in 1951 due to a lack of riders. Ironically, Westchester began to experience significant growth only a few years after the line was abandoned by the CTA.

Normal Park Branch

Less than a mile long, the Normal Park Branch ran from the main South Line (Green Line) in Englewood at Harvard St. south to 69th St, serving four stations along the way. It opened on May 25, 1907 but it never attracted many passengers. By late 1953 it was generating less than 100 fares a day, barely enough for a bus line but not for rapid transit service. The CTA shut down the line on Jan. 29, 1954.

Garfield Park Line

Garfield Park Line

Opened in 1895, the Garfield Park Line ran from the Wells Street Terminal in the Loop (Wells and Quincy) paralleling Van Buren and Congress all the way to the western edge of the city (Cicero Ave.) and, eventually, to the near west suburbs (Oak Park, Bellwood, Maywood). When the Congress Expressway (Eisenhower) was under construction in the mid 1950s, the 50-plus year Garfield Park Line was demolished in favor of a new rail line (Blue Line) that would occupy the median of the new expressway.

For a fun CTA train experience and to see what remains of the old lines, consider booking a Chicago walking tour with L Stop Tours!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Robots build cars, computers fly airplanes, telephones dial themselves and coffee makers have a hot cup brewed before their owners wake up in the morning.

Has everything in the western world become electrified and digital?

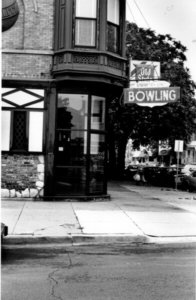

Purists and those who despise progress will be happy to learn that Chicago’s Southport Lanes, a four-lane bowling alley located at 3325 N. Southport, is continuing a tradition established on its first day of business in 1914. The alley remains one of the last places in America that still utilizes human — not automatic — pinsetters.

The operative question here is “why?”

Why would an establishment like Southport Lanes Bowling Alley resist an invention that 99.9 percent of all other bowling alleys embraced decades ago?

Many years ago, owner Leo Beitz, now deceased, told the Chicago Sun-Times, that he never even thought about going automatic. Business was thriving, he told the paper.

Thriving indeed. Southport Lanes features bowling leagues most days of the week and private parties are a steady business on evenings and weekends.

Bowlers can’t get enough of the place. Because it contains only four alleys, Southport Lanes’ maximum capacity is 16 bowlers. Such physical intimacy forces people to be friendly and courteous to one another while they bowl.

The real appeal of the alley, however, is the human “element” — the pinsetters — who toil endlessly in the back of the alleys to make sure that all 10 pins are in proper position for the beginning of each frame.

What’s it like to be a pinsetter at Southport Lanes Bowling Alley?

Once each ball is thrown, the pinsetters jump down from a perch that’s located above the pin area. After the first ball of each frame, setters pick up downed pins, place them in a rack above the lane, roll the ball back to the bowler on an incline and quickly jump back onto the perch.

Following the second ball of each frame, the setters again jump down from their perches, put the remaining pins in their racks and lower them with a cord to reset the standard 10-pin formation. The ball is again rolled back to the bowler and the setter hops back up onto his perch.

Is the job dangerous?

“I’ve been hit by the pins a few times, also in the back and in the legs,” said one pinsetter who wished to remain anonymous. “But it’s just a little sting, that’s all.”

Because of the physical stress involved with the job, there are approximately 10 pinsetters employed by the bowling alley, each working two or three night per week with another setter (each is responsible for clearing and setting two alleys). The majority of the setters work at the alley for about six months to a year. Some last only one night.

They’re paid well, however, for their efforts. And whenever they work private parties, there’s always the possibility of additional income from tips.

There’s one other advantage to employment at Southport Lanes. It’s perhaps the only job in America where having a split personality appears to be a decided plus.

You can visit Southport Lanes by going on the Brown Line. L Stop Tours also hosts a Chicago city tour via the Brown Line that shows visitors the unique history of the city’s oldest pubs. Visit our Chicago historic pub tour page to learn more about our River North tour.

Update: Southport Lanes is now closed.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

The Cutler mail chute was not invented or manufactured in Chicago. But because it made Chicago skyscrapers more efficient and economical — and because Chicago is considered the “home” of the modern skyscraper — the Cutler mail chute, by extension, was a significant contributor to the growth of Chicago, particularly in the city’s formative years after the fire (1871).

How it worked

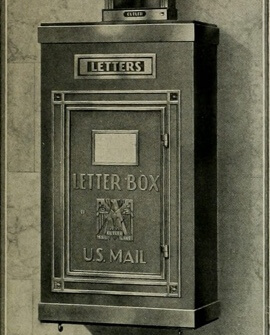

In 1883, James G. Cutler received a patent for his letter collection system that was designed to be used exclusively in multi-story office buildings, hotels, apartment buildings and other high rise structures. In 1884 the very first mail chute and letterbox system was installed in the Elwood Building in Rochester, N.Y. Instead of traversing all the way to the building’s lobby in order to mail a letter, building occupants simply dropped mail into a glass-enclosed chute and gravity would take over. The mail would “swoosh” its way down to a box in the lobby where it was collected by postal service employees.

Why was this important? Consider an early Chicago skyscraper, the historic Monadnock Building. When it was completed in 1893, the 16-story Monadnock was the largest office building in the world, the tallest load-bearing brick building ever constructed and was one of the first buildings in the City to be wired for electricity. It featured 1,200 rooms and had an occupancy of over 6,000.

Because of its sheer size, the Monadnock Building was a postal district unto itself. It employed four full-time carriers to deliver mail to building occupants six times a day, six days per week. While this might seem excessive by today’s standards, consider that without modern and reliable communications systems (telephone systems were still in their infancy), occupants in the early Chicago skyscrapers were relatively isolated from other activities that were happening at street level and throughout the city. Timely, regular mail service was a necessity for businesses of that era — but it was also costly for the building to maintain.

Enter Cutler and his mail chute/letter collection system — the perfect solution for a huge skyscraper like the Monadnock. Not only did the system make the mailing process more convenient for tenants, it enabled the building to save time and money. Postal carriers to the building’s offices were no longer needed. Outgoing mail was now collected in a single location by a common carrier.

What about now?

Thanks to email, texting and modern mail rooms with tenant mailboxes, the mail chute has largely become a defunct letter collection device in high rises across the nation. Tenants often folded their mail so it would fit into the chute, but that only made matters worse because it would often unravel and clog the chute. Often it took days — sometimes weeks — for someone to notice that chute was clogged with old mail.

Monadnock Building

Though they have been removed from many office buildings in the last several years, it is estimated that approximately 360 mail chutes remain in use in Chicago skyscrapers nd high rise buildings. You can view two of these that are still in use on L Stop Tours’ Blue Line Tour— at the Monadnock Building and at the Fine Arts Building.

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Still a Big Hotel With a Lot of History

In the late 1920s, Chicago was known as the City of Big Shoulders, but more to the point it was simply the “City of Big.” Within its boundaries were the world’s largest office building (the Merchandise Mart), the world’s largest store (Sears Roebuck and Co.), the world’s largest livestock marketing facility (Union Stock Yards) and the world’s largest hotel (The Stevens).

In those days, apparently, everything was not bigger in Texas.

Although all of these businesses enjoyed long reigns as “the world’s largest,” all four have since given up their titles — the Merchandise Mart was supplanted in size by the Pentagon; Sears has shrunk to less than 400 stores and is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy; the Union Stock Yards have been closed 1971; and, as of this writing, the Hilton Chicago (formerly the Stevens) is only the 93rd largest hotel in the world.

Though the superlative of “World’s Largest” is no longer attached, the Hilton Chicago is still a spectacular and magnificent hotel. It oozes with history, is lavishly styled and is blessed with one of the most desirable and well-situated land parcels in the entire city of Chicago. It is across the street from beautiful Grant Park, only a couple of blocks from Lake Michigan and is an anchor property on South Michigan Avenue.

Still an Enormous Hotel

The hotel occupies a full city block with 1,544 rooms spread over 30 floors (down from 3,000 when the hotel opened in 1927). It has 1,000 employees, and an incredible 234,000 square feet of meeting and event space. It offers 36 regular suites and 13 specialty suites for guests who want a more than just a room. The suites range in size from 1,000- to 2,500 square feet and every one of them has a magnificent view of Lake Michigan.

One of the suites at the hotel, the Conrad Suite, has earned a reputation as one of the most spacious and opulent hotel suites in the world. When the hotel underwent a major renovation in 1985, two former ballrooms on the top two floors of the hotel were combined and redesigned into a single suite at a cost of $1.6 million. It has all the comforts of home and then some. The amenities include a grand salon with fireplace (1,900 square feet), a dining area for fourteen, a classic library, private kitchen, three bedrooms with full baths, two powder rooms, and four private elevators. The décor features gold and crystal Strauss chandeliers, large floral oriental rugs, mahogany parquet floors, period antique furnishing and artwork. If you can afford $10,000 per night, you can stay there as long as you wish.

The 8th Wonder: Large and Lavish

Built at a cost of $30 million, the Stevens Hotel was considered by many to be the eighth wonder of the world because of its sheer size. It was, essentially, a city unto itself. In addition to the hotel’s own private areas (heating and cooling systems, laundry, kitchens, electrical, carpentry and plumbing shops, etc.) the property featured a wide variety of services and features for guests. These included a rooftop miniature golf course, a drug store, cleaners, a children’s clothing and toy store, a beauty shop, a jewelry store, haberdashery, and flower shop. There was also a concert music library, a recreation room, a children’s playroom, several restaurants, and even a small hospital with an operating room. To top it off, the hotel had a 1,200-seat theater with “talking motion picture equipment, a seven-chair barbershop, and its own ice cream and candy manufacturing facilities.

The hotel was the brainchild of James W. Stevens, his son, Ernest, and their family. They ran the Illinois Life Insurance Company and owned the nearby La Salle Hotel. James Stevens was the grandfather and Ernest was the father of former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

From Opening Day on, the hotel was the place to be — and be seen — in Chicago. The first guest booked into the hotel was the Vice President of the United States, Charles G. Dawes; the second guest was President Machado of Cuba. Galas and special events filled the ballrooms night after night — a dinner honoring Charles A. Lindbergh; the Motion Picture Association Ball, attended by movie mogul Cecil B. de Mille and actor Victor McLagan; and many more.

But the good times didn’t last…

In the weeks and months following the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, the large hotel fell on hard times. Fewer and fewer guests booked rooms and the dining areas and ballrooms were barely used. During the Depression it is estimated that some eighty-one percent of hotels in the United States went bankrupt. In June of 1934 the seven-year-old Stevens fell victim to this trend and was declared insolvent. In 1937, the hotel was appraised for $7 million, a whopping 78 percent decrease in its value in only a decade.

Perhaps one of the most interesting eras in the illustrious history of the Stevens was launched in 1942 when it was purchased for $6 million by the U.S. Army and became the Army Air Force Technical Training School for more than 10,000 air cadets who used the hotel’s 3,000 rooms as barracks.

In February 1945, hotel magnate Conrad Hilton purchased the large hotel from a local businessman, Stephen Healy, who earlier had bought it from the Army and converted it back to a hotel. Shortly after buying the property, Hilton made improvements, which included the installation of an ice stage in the Boulevard Room that hosted elaborate ice shows nightly. Hilton also initiated extensive training sessions with his employees in an effort to become the “friendliest” hotel in Chicago.

Over the years, Conrad Hilton enticed many stars of stage, screen, sports and politics to entertain at or visit the hotel — Eddie Duchin, Guy Lombardo, John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Babe Ruth, Grace Kelly, Tony Bennett and Dean Martin, Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower, were a few of the guests he welcomed to the hotel. Hilton’s crowning achievement, however, was in 1959 when Queen Elizabeth II became a guest at the hotel.

Today’s Hilton: Still huge

In the past two decades, the Hilton Chicago has gained a reputation as a great place to film movies. Among popular Hollywood movies filmed at the hotel were “U.S. Marshalls,” “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” “Home Alone II” and “Road to Perdition.” The most memorable, however, was probably 1993’s “The Fugitive,” starring Harrison Ford and Tommie Lee Jones. In the final memorable chase scene, virtually the entire hotel is showcased. Look closely and you’ll see the Grand Ballroom, the Great Hall, the International Ballroom, a suite’s library, the roof promenade, and the hotel’s laundry.

Today, the hotel is as hip and in touch with the times as ever. It has many received several awards and recognition for sustainability programs. A large portion of the roof on the eighth floor is actually an urban garden that is cultivated in partnership with Windy City Harvest. This organization trains students how to grow organic, sustainable fruits and vegetables in an urban environment. Much of the produce is consumed at the hotel. Find the hotel when exploring the South Loop. (Accessible via the Blue Line, Green Line and Pink Line, Purple Line and Orange Line).

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

When Chicago’s Lakefront Wasn’t So Green

Only on rare occasions is a first-time visitor not impressed by Chicago’s 22 miles of shoreline. In addition to the beauty and grandeur of the sparkling blue water, virtually the entire stretch is free and clear of commercial construction. It consists of nothing but open space — parks and beaches — and is always open and accessible to the general public.

It wasn’t always that way, however. During the past century, Chicago’s lakefront served as the home for facilities and installations that emphasized weaponry — something that is difficult to imagine in today’s sensitive and politically-correct times.

Nike Missile Sites

From the early 1950’s until 1974, Chicago’s lakefront hosted Nike Missile installations (missiles, missile launchers and radar facilities) at three locations — Belmont/Montrose harbor, Burnham Park and Jackson Park/Promontory point. The sites were built by the U.S. government as part of a Cold War defense system and a deterrent to possible aggression from the Soviet Union. Though not usually visible to the general public, the missiles were occasionally unveiled so that citizens could see for themselves that the U.S. was prepared to defend the homeland and also as a propaganda tool to show the Soviets that the U.S. was “armed to the teeth” in case they were considering an attack. By the early 1960s, the sites became obsolete when intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) became the new offensive/defensive missiles-of-choice by both the Soviet Union and U.S. governments. As a result, the sites were dismantled.

Lincoln Park Gun Club

From 1912 until 1991, members of a private gun club founded by such prominent Chicagoans as Oscar F. Mayer, W.C. Peacock and P.K. Wrigley, were allowed to shoot traps and skeet that were launched over Lake Michigan by hurling devices operated by the Club, which was located near Diversey Avenue and the lakefront. In addition to the ubiquitous “pop-pop-pop” of gunfire echoing across the lakefront, lead shot from spent shotgun shells continuously emptied into the Lake and, over time, became a significant environmental hazard and pollutant. The Club, which leased its facilities from the Chicago Park District, decided to shut down in 1991 when then-Illinois Attorney General Roland Burris sued it for allegedly polluting Lake Michigan. When the Club’s countersuit against the Park District was dismissed, the club’s buildings were demolished by the Park District.

Today, the former Nike Missile sites and the land once occupied by the Lincoln Park Gun Club have been reclaimed as green space by the Chicago Park District and are open and accessible to all. The lake bottom at and around Diversey Harbor has been dredged many times in ongoing efforts to removed lead from the water.

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Deep Dish Pizza Celebrates 75th Birthday. But who invented it?

(Adapted from an article that first appeared in the Chicago File, March 1987.)

Many around the world are familiar with Chicago’s deep-dish pizza. Few, however, know who is responsible for inventing this gastronomic gut bomb, or even where it originated.

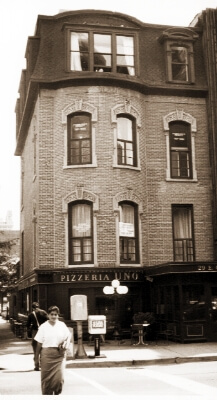

It began in 1943 — 75 years ago — when a Texas-born liquor salesman, Ike Sewell, came to Chicago and befriended Ric Riccardo, Sr., the owner of a popular Rush Street restaurant, Riccardo’s. The two discussed opening a restaurant together, but had different ideas on what to serve.

Sewell wanted to open a Mexican restaurant and serve the kind of food he enjoyed as a boy in Texas. He was convinced such an establishment would be successful because there weren’t any Mexican restaurants in Chicago’s Loop or on the Near North Side.

Mexican food did not agree with Riccardo, who often became ill upon consuming it. Riccardo suggested the restaurant serve pizza instead.

Sewell liked the pizza idea because only a few establishments between Chicago and the East Coast were serving it. But Sewell thought that pizza should be more than just an appetizer, he felt it should be closer to a meal than a snack.

Sewell and Riccardo experimented until they came up with a far thicker pizza product that has since become legendary.

But at first it didn’t sell, no one knew what it was. So Sewell, ever the marketer, gave away free samples of the deep-dish pizza for several months after Pizzeria Uno opened. After a newspaper reporter raved about the deep dish in an article, which helped ensure the future success of Uno’s.

In 1955, Pizzeria Due opened just down the street, a by-product of Uno’s success. And in 1963, Sewell opened the Mexican restaurant he had dreamed about for years, Su Casa.

Sewell always felt that maintaining the quality of pizza in locations other than Chicago would be difficult — so for a long time he resisted several offers to franchise his deep-dish pizza operation.

But in 1976, Sewell gave in and sold the rights to his restaurant’s name and product. Today there are 110 Uno’s Pizzeria and Grill restaurants in 21 states, and there are also restaurants in United Arab Emirates, Honduras, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

Riccardo passed away in 1954 and Sewell died in 1990. Their original place of business — Uno’s at 29 E. Ohio — and the legendary product they developed — deep dish pizza — will undoubtedly survive us all.

Check it out for yourself. Uno’s is a five-minute walk from the Grand Avenue stop on the CTA’s Red Line.

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Harold Washington: A New Kind of Mayor

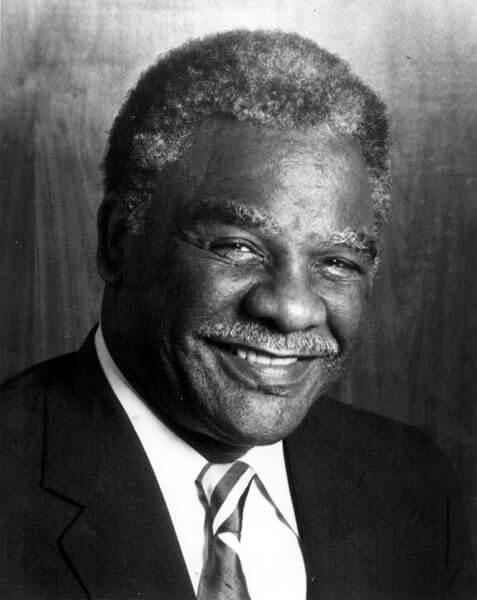

On April 12, 1983, more than 35 years ago, Harold Washington was elected Chicago’s first African American Mayor. He won the race because he amassed a never-before-assembled coalition of local supporters — African Americans, Latinos and “progressive whites” — all of whom voted for him in droves. In doing so, Washington was the first candidate to beat Chicago’s long-entrenched Democratic “Machine,” the veritable puppet-master behind all Cook County elections for the previous 60 years.

Harold Washington was much more than just a savvy political strategist and tactician, however. Although he was in office a little more than four years (his second term was cut short by a fatal heart attack), Washington accomplished much during his tenure as mayor. He is noted for increasing the number of underrepresented groups in city government and in city contracts, making government more open and transparent, achieving more balanced economic development between neighborhoods and downtown and for opening the city’s budget process for public input and participation.

Harold Washington Library Exhibit: An Undiscovered Gem

Washington was also a leading proponent for building a new central Chicago Library in Chicago’s South Loop and created a citywide cultural plan to help make it happen. His efforts to make the library a reality are the reason why it bears his name today.

On the 9th floor, immediately adjacent to the Library’s beautiful Winter Garden, is a permanent exhibit in the Special Collections Exhibit Hall that contains pictures, tapes, artifacts and documents from the life and political career of Harold Washington, 42nd mayor of Chicago. It doesn’t receive the attention or publicity that other Chicago museums do and, as a result, is an uncrowded, undiscovered downtown gem.

L Stop Tours is proud to have the Harold Washington Library, the Winter Garden and the special exhibition on Mayor Harold Washington as part of our Blue Line North Tour.

The Harold Washington Library L Stop

Harold Washington Library

Winter Garden on the 9th Floor

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.