Stevedores, Soldiers, Students, and Sightseers: The Evolution of Navy Pier

In 2024, it’s not difficult to pinpoint the category of business that Navy Pier is in. With a plethora of parks, restaurants, rides, attractions and special event space, this three-quarters of a mile long pier in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood is clearly in the entertainment category.

Over the years, however, this has not always been the case. Since its construction in 1916, Navy Pier has served Chicago in a number of capacities — as a steamship and cargo terminal, a naval training base, a university, the home of an annual music festival and one of the city’s leading tourist attractions. Architecturally-speaking, Navy Pier is one of the city’s best examples of “adaptive reuse,” a building that is reconfigured from one use to another, primarily via renovation.

Below are some of the different roles Navy Pier has played over the decades:

Plan of Chicago (1909)

Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago envisioned five new municipal piers that would be evenly spaced along the lakefront. The piers would be designed to serve both passenger and freight traffic utilizing an innovative shed-like construction that offered storage for cargo and a wide range of services for steamship passengers. The piers themselves would keep boats from plying the already crowded waters of the Chicago River and also provide recreational space for local residents.

![r/InfrastructurePorn - Municipal Pier in Chicago IL c.1920 [1749 x 868]](https://c2.staticflickr.com/4/3938/14970965433_3aee5d43c4_o.jpg)

Municipal Pier (1916)

A new, 3,300-foot-long pier encompassing over 50 acres opened on the north bank of the Chicago River in 1916. Named Municipal Pier, it resembled an exclamation mark that was thrust into the choppy waters of Lake Michigan. In addition to operating as a loading and unloading zone for commercial vessels, the pier featured a headhouse (the entrance) on the west end and a beautiful ballroom on the east end where Chicagoans were quick to attend a wide range of pageants, shows and exhibitions, making the pier one of the city’s most popular attractions.

![r/InfrastructurePorn - Municipal Pier in Chicago IL c.1920 [1749 x 868]](https://c2.staticflickr.com/4/3938/14970965433_3aee5d43c4_o.jpg) First Wave of Entertainment (1920s)

First Wave of Entertainment (1920s)

While still serving freight traffic, the pier became a full-fledged entertainment destination, with live bands, plays, art exhibits, children’s activities, fireworks displays, and airplane and motorboat races. A streetcar line was added to the second floor of the structure allowing easy access to all piers and gates. In 1921, Mayor Bill Thompson launched a mini world’s fair called the “Pageant of Progress” which attracted nearly two million people in a two-week period. In 1927, Municipal Pier is renamed “Navy Pier” to honor the naval veterans who served in World War I.

Pier Slips in Importance (1926-31)

The rise of the automobile and Chicago’s position as the nation’s rail hub played key roles in diverting passenger and freight away from Navy Pier. During this five-year period, steamship passengers declined nearly 50 percent — from 471,000 to 258,000 passengers.

World’s Fair and U.S. Navy Help Pier Recover (1933-45)

Chicago’s Second World’s Fair — “A Century of Progress” — helped rejuvenate the pier from the depths of the Depression with crowds not seen in decades (1933). In 1941, as the U.S. entered World War II, Navy Pier was designated a full-fledged naval training school, where more than 60,000 sailors and 18,000 pilots, including future U.S. President George H.W. Bush, completed their basic training.

University of Illinois at Navy Pier (1946-1965)

Sky-high demand for college education (returning soldiers on the G.I. Bill) forced colleges and universities across the country to expand their campus offerings. The University of Illinois decided to open a branch in Chicago at Navy Pier, a location that was 140 miles north of its downstate Champaign campus. Nicknamed “Harvard on the Rocks” because of its unique shoreside location, the university operated as a two-year college until a new campus was constructed on the near West Side in 1965. Today the school is known as the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Lean Years for the Pier (1966-1977)

The newly-rebuilt McCormick Place Convention Center (the original building was destroyed by fire) stole what little convention business Navy Pier enjoyed during the construction phase of the new exhibition hall. In the mid-1960s, more than 250 ocean liners docked at Navy Pier but by 1974, that number had dropped to just 20. Lean years caused the near-empty pier to fall into general disrepair.

Chicago Fest (1978-82)

After some much-needed renovations, the city introduced Chicago Festat Navy Pier. This week-long music festival featured 16 separate stages, each sponsored by a national retail brand and a media sponsor compatible to the stage’s format. Specifically, the stages were: Rock, Classic Rock, Country, Blues, Comedy, Roller Disco, Pinball Arcade, Jazz, Children’s, Variety, Ethnic, as well as a main stage with seating for 30,000 attendees. The hugely successful Music Festival, launched in 1979 by Mayor Michael Bilandic, eventually morphed into the Taste of Chicago and moved from Navy Pier to Grant Park.

A Return to its Roots (2016)

In 2015, the City began to take a hard look at the big idea of redeveloping Navy Pier into both a commercial and recreation center — similar to its original purpose and mission in 1916. The solution was another renovation, one that would cement its status as a tourist destination and would reflect many of the experiences that people enjoyed during its golden age in the 1920s. The terminal sheds were destroyed; in their place, Festival Hall, Crystal Gardens, restaurants, shops and kiosks, a park with mini-golf and flying swings and towering above it all, a 146-foot-tall Ferris Wheel paying homage to Daniel Burnham’s 1893 World’s Fair. Summer fireworks occurred every Wednesday and Saturday to music. Chicagoans could once again take pleasure cruises to various locations throughout the city. Concerts returned to the auditorium. The former headhouse became home to the Chicago Children’s Museum. Today, Navy Pier is one of Chicago’s leading tourist attractions.

Looking for a place to get you in the holiday mood? We’ve put together a list of ten Chicago places that are sure to raise your holiday spirits.

- Millennium Park

- Museum of Science and Industry – Christmas Around the World

- Butch McGuire’s – holiday decorations galore!

- Macy’s and the Walnut Room

- Chicago Botanic Garden (Lightscape)

- Art Institute

- Daley Center Plaza/Christkindlmarket

- Lincoln Park Zoo & Zoo Lights

- Garfield Park Conservatory and Winter Flower Show

- CTA Holiday Train

Millennium Park

During the warmer days of spring, summer and fall, “the Bean,” Crown Fountain and Pritzker Pavilion take center stage at Millennium Park. In November and December, that honor belongs to the City of Chicago’s municipal Christmas tree, which is located in the front of the park, adjacent to the skating rink. This year’s tree is a 45-foot Colorado spruce that was donated by a family in suburban Darien. With every square inch of the tree covered with colorful lights, the city’s Christmas tree is sure to make your spirits bright.

Museum of Science and Industry

Now in its 81st year, the Museum’s Christmas Around the World and Holidays of Light exhibit is a beloved holiday tradition that has been enjoyed by millions of visitors over the years. It includes a festive, 45-foot tree that is surrounded by 50 smaller trees that have been decorated by local volunteers to represent holiday traditions from around the globe. It’s a one-of-a-kind experience that brings a whole world of holiday celebrations under one roof.

Butch McGuire’s

Many businesses throughout the Chicago area decorate their businesses for the holidays, but few can match the over-the-top spectacle of sheer holiday madness that covers every square inch of space throughout Butch McGuire’s tavern on the near North Side. Unlike pop-up Christmas bars that began appearing on the scene 5-10 years ago, Butch McGuire’s has been decorating its tavern with holiday gizmos and gadgets since 1961. To really get into the spirit of the season, be sure to order a “Christmas in Your Mouth” martini when you visit.

Macy’s

The second largest department store in the U.S., Macy’s State Street is a cornucopia of delights during the holiday season. Every department is decorated with festive holiday decor; display windows on State and Randolph streets tell wonderful holiday stories and “The Great Tree” in the Walnut Room on the seventh floor is still the place to gather with your children, grandchildren, family or friends for a heaping dose of holiday cheer.

Chicago Botanic Garden: Lightscape

If dazzling holiday light shows and brightly lit landscapes are what you seek, venture to the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe for “Lightscape,” a holiday light extravaganza beyond reproach. This year’s exhibition includes 5-foot water lilies floating elegantly on water and delicate lamp-shaped lights with soft ambient colors extending 19 feet high. Additionally, favorites from previous years, like the Winter Cathedral, make a return visit to the illuminated pathway.

Art Institute Lions

Sometimes, all you need to get in the spirit of the season is a sign that cheerier days are ahead. For me, one of those small signs that the holidays are almost upon us is when the statuesque lions at the front entrance of the Art Institute (Michigan Ave.) display their annual Christmas wreaths with beautiful bright red bows. A quick glance and a huge smile spreads across my face — a sure sign that the joyful holiday season is nigh.

Christkindlmarket at Daley Center Plaza

Hot spiced wine, potato pancakes, currywurst, German pastries, hand-crafted gifts, glass ornaments, seasonal music and carolers — it’s hard not to get in the spirit at the Christkindlmarket, an authentic German and European holiday market that is now in its 23rd season. This year there are two additional locations for the Christkindlmarket – Wrigleyville and Aurora.

Lincoln Park Zoo — Zoo Lights

The Lincoln Park Zoo’s featured holiday attraction, allows you to walk through 50 acres of zoo property that is dazzlingly-illuminated by millions of colorful lights with holiday music playing softly in the background. If you’re lucky, a light snow will begin falling just as you start your journey through the complex. While wandering through the site, visitors will also encounter costumed characters, Victorian carolers, ice sculptors and special lighted exhibits.

Garfield Park Conservatory

When the holiday season is too overwhelming, a trip to the flower show is exactly what you need. Garfield Park’s Winter Flower Show, Serenity, evokes a feeling of tranquility to remind visitors that the natural world is a great source of calm amidst the hectic season. Pink poinsettias will help to calm anxiety, while plants with silver foliage will relax the mind. Pleasant scents remind visitors of the outdoors and provide aromatherapy throughout the room. New this year, the show features many blooming flowers, which is atypical for a display during winter’s shorter days. Blossoms such as hyacinth, zinnias, salvias and cosmos fill the room with their own brand of peace on earth.

CTA Holiday Train

Nothing brightens your spirits more than stepping aboard the CTA holiday train. A beloved Chicago tradition for more than 30 years, the holiday train makes its way through the city throughout December. Marvel at the six-car train decorated with holiday scenes and thousands of sparkling lights, then hop on board to meet the elves handing out candy. Don’t forget to wave to Santa, whose sled replaces the head car. There’s also a holiday bus that traverses the city streets, bringing holiday cheer to neighborhoods throughout Chicago.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Situated on the lakefront between Lakeview on the south and Edgewater on the north, Uptown is a vibrant, diverse neighborhood with roots dating back to the 1880s. Nearby Argyle Street, home to many Asian-owned retail shops and restaurants, is a small, mini-neighborhood located in the northeastern corner of Uptown. Together they form one of the most dynamic and distinctive communities on Chicago’s North Side.

Uptown

Uptown has a unique history. Initially inhabited by Swedish and German farmers, real estate developers noticed the desirability of the area when the Northwestern Elevated Railway Company opened a terminal at Wilson and Broadway (today’s Red Line) in 1900 and initiated train service to the Loop. In 1915, a local merchant opened a branch of his Loren Miller & Company department store (later Goldblatt’s) on Broadway south of Lawrence. He called it the “Uptown Store” to differentiate it from its Loop counterpart and soon it became the unofficial (and later, official) name for the neighborhood.

Over the years, Uptown has evolved in a number of different ways: For decades it was a “get-away” spot for city dwellers who wanted to get away from the rat race of the Loop; it served as the center of America’s motion picture industry in the early 1900s (before the business relocated west to Hollywood); served as a shopping, entertainment and dining destination for generations of Chicagoans; and continues to this day to serve as a port of entry for Chicago’s newest arrivals, immigrants, who are seeking a better life for themselves and their families.

Argyle Street

Argyle Street, on the other hand, is a relatively new neighborhood located in an older part of town. The area got its start as Argyle Park, a northern suburb of Chicago that was annexed by the city in 1889. It was named by Chicago Alderman James A. Campbell for his ancestors in Scotland (the Dukes of Argyll). Shortly thereafter, the main thoroughfare running through the area was Anglicized and named Argyle St. (5000 North).

It wasn’t until the 1960s that Argyle Street underwent a “rebirth” that put it on the radar of most Chicagoans. Well-known Chicago restaurateur Jimmy Wong bought property in the area and began to turn it into “New Chinatown” a North-Side enclave that he felt could rival Chicago’s older and more established Chinatown on the South Side (Archer and Wentworth). Wong was convinced Chicago could support two Asian entertainment districts. Today, Argyle Street has a pan-Asian population that features a wide array of Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian and Thai restaurants, grocery stores, bakeries and other businesses that are Asian-owned.

Self Guided Tour

The Uptown/Argyle Street neighborhood is loaded with interesting sites and places of interest — perfect for a self-guided tour, courtesy of L Stop Tours, Chicago’s unique neighborhood tour company.

Castlewood Terrace

(4900 North, 800 to 957 West)

An unusual one-block street consisting of 26 well-appointed single-family houses built between 1897 and 1927 in a neighborhood that contains an inordinate amount of high-rise apartment buildings. Named for the developer, Charles W. Castle and also the woods that bordered the area on the north side of the street, Castlewood Terrace homeowners resisted high-rise developments on their street and worked hard to maintain the single-family home status quo. Their efforts paid off, in 2009 the district was added to the National Register of Historic Places and now qualifies for preservation at the federal level.

The Green Mill

4802 N. Broadway

Opened in 1907 as Pop Morse’s Roadhouse, this swinging jazz joint became known as the Green Mill in 1910 and has been serving up great music and entertainment ever since. During Prohibition, “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn, a member of Al Capone’s gang, became a part-owner of the club. He had tunnels constructed that led to the street adjacent to the building so mobsters could slip out of the club unnoticed, if necessary. Today the Green Mill hosts a wide variety of musical acts and hosts one of the nation’s oldest poetry slams on Sunday nights.

Baton Show Lounge

4713 N. Broadway

After more than 50 years operating a successful all-male revue in River North, the Baton Show Lounge relocated its female impersonation show and cabaret to the Uptown neighborhood in 2018. Over the years, the Baton has elevated female impersonation to an art form as is known nationally for the high entertainment value of its shows. Celebrities that have attended Baton shows include Oprah Winfrey, Madonna, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, Sammy Davis, Jr., Ted Kennedy, Lauren Bacall and Liza Minnelli.

Essanay Studios

1345 W. Argyle

From 1907 to 1917, Chicago was the motion picture capital of the world and one of its busiest and most popular studios was located on West Argyle Street, Essanay Studios. The name was a play on the initials of the two founders, George K. Spoor and Gilbert Anderson (“S and A”). Essanay produced silent films and had a stable of stars that included Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin, Wallace Beery, Francis X. Bushman and Gloria Swanson. One of Chaplin’s most popular and best-known films, The Tramp, was produced and distributed by Essanay in 1915. Eventually, Chicago lost out to the warmer climes of Hollywood and the Essanay Studio changed hands several times over the years. Today the building is part of St. Augustine’s College and its main meeting hall has been named the Charlie Chaplin Auditorium.

Roots of Argyle Mural

SW Corner of Winthrop and Argyle Streets

The mural, located on the side of the Hoa Nam grocery store, is a centennial celebration of the historic movers and shakers of the Argyle Street community. The mural utilizes the existing front doorway facade of the old Essanay Studios as the main architectural motif of the painting which depicts immigrants passing through doorways to their new life in the Argyle Street community.

Bridgeview Bank Building

4753 N. Broadway

Built in 1924, this historic building was originally known as the Sheridan Trust and Savings Bank and was designed by the same architects who conceived the Drake and Blackstone hotels downtown. When that institution failed in 1931, it became the Uptown National Bank and in 2003 it became the Bridgeview Bank. Designated a landmark in 2007, the 12-story neoclassical building was recently sold and is currently in the process of being converted into 175 rental apartments by the new owner. If the rounded corners of the triangular-shaped building looks familiar to you, it might be because it was used extensively in the 2009 motion picture Public Enemies.

Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary

Montrose and Lake Michigan

Overlooking Lake Michigan at Montrose Ave. is the Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary, a 10-acre prairie-like park that hosts thousands of seasonal migratory birds, particularly in the spring and fall. The park’s signature attraction is a 400-foot strip of trees and shrubbery called the “Magic Hedge” for its mysterious ability to regularly attract a wide range of birds, including warblers, sparrows, sandpipers, purple martins, woodpeckers and owls. A special bonus of the Sanctuary is its spectacular over-the-water view of Chicago’s skyline.

Aragon Ballroom

1106 W. Lawrence

Built in 1926, the Aragon is a massive dance hall that’s designed to resemble a Spanish village, replete with twinkling stars on its domed ceiling. In its first four decades of operation, the Aragon was the place to dance in Chicago — all of the popular bands played there and powerhouse radio station WGN-AM broadcast a one-hour program nightly live from the Aragon to listeners in 36 states and Canada. By 1964, however, the world had changed and so did the Aragon. Since then it has survived by holding huge rock concerts, hosting boxing matches, served as a roller rink and also as a disco. Today it hosts a variety of smaller rock concerts.

Riviera Theatre

4746 N. Racine

Built in 1917 for the Balaban and Katz chain of Chicago theatres at a cost of half a million dollars, the Riviera opened to the general public primarily as a movie theatre but with occasional bookings for concerts. The beautiful French Renaissance Revival-style building could accommodate 2,500 patrons and quickly became a favorite of local residents who were looking for fun and intrigue in Uptown’s burgeoning entertainment district. The theatre stopped showing movies in the late 1970s and shifted entirely to live entertainment, which it continues to host to this day.

Clifton Avenue Street Art Gallery

Adjacent to Wilson Ave. Red Line Station

This “open air” art gallery incudes more than 70 large-scale murals from artists all over the world and is located between Wilson Avenue and North Broadway. Developed by Uptown United, a community organization, in 2019, the gallery brightens up an old, dingy alley and marks a new cultural destination in Uptown.

West Argyle Street Historic District

North Broadway Ave. and West Argyle Street

This 41-acre Asian community is located largely within these boundaries: North Glenwood on the west, Winona Street on the north, Sheridan Rd. on the east and Ainsley Street on the South. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the West Argyle Street Historic District is characterized by a conglomeration of Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian and Thai restaurants, bakeries, grocery stores and small retail shops. The neighborhood also is known for its “Taste of Argyle” food festival, held annually in the summer months.

Haitian American Museum of Chicago

4654 N. Racine Ave.

A long-time port of entry for generations of immigrants, Uptown is a fitting location for the Haitian American Museum of Chicago, a gathering place where Chicagoans and visitors explore Haitian art, culture and history. Since 2012, the museum has hosted a wide array of exhibits showcasing Haiti’s rich culture and complex history.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Andersonville is accessible via the Red Line Berwyn L Stop.

A Swedish Community

From the early 1800s until 1960, Swedes ranked as Chicago’s fifth-largest foreign-born group, behind Poles, Germans, Russians and Italians. For the most part, Swedes congregated in neighborhoods on the Near North Side of the city, especially in areas such as Lincoln Park and Lakeview. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, large numbers of Swedes moved farther north in order to escape the city’s new, strict building code which prohibited the use of wood in residential construction (and therefore made house construction more expensive).

One of the areas settled by Swedes was a bucolic subdivision about 6 miles north of the Loop (present-day intersection of Clark Street and Foster Ave.) called Andersonville. The residential development was named, ironically, after a Norwegian community leader, Reverend Paul Andersen, whose name was often misspelled with an “e” instead of an “o.” It grew to become a thriving community of Swedes until the Great Depression when many decided to relocate to the nearby Chicago suburbs.

Today’s Andersonville

Not all Swedes left the neighborhood, however. In 1964, Andersonville was rededicated as a community by Mayor Richard J. Daley and Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, and to celebrate the occasion the Andersonville Chamber of Commerce reinstituted the Swedish tradition of celebrating the summer solstice by hosting Midsommarfest, one of the neighborhood’s largest and most popular outdoor festivals. To honor the contributions of early Swedish immigrants to the area, local residents opened a Swedish American Museum with a gala ceremony that was attended by King Carl XVI Gustav of Sweden.

Today, Andersonville is a diverse and vibrant community comprised of third- and fourth-generation Swedes, Mexicans, Koreans and Lebanese. Andersonville also is home to a thriving LBGTQ population as well as a pastiche of independent, locally-owned businesses that give the area a strong sense of both family and community.

We’ve put together a self-guided tour of Andersonville that helps you discover some of the area’s points of interest:

Swedish American Museum, 5211 N. Clark St.

Founded in 1976, the Swedish American Museum is a repository of Swedish art, history and culture. The Museum’s main exhibit, “The Dream of America: Swedish Immigration to Chicago,” displays hundreds of artifacts, pictures and descriptions of the mass immigration of Swedes to Chicago beginning in the late 1800s. Visitors learn about the struggle these immigrants faced and how they forged new lives in their new land. The first floor of the museum is filled with artifacts created by contemporary Swedish and Swedish-American artists and craftsmen. For anyone visiting Andersonville, the Swedish American Museum is the ideal first stop on a self-guided tour.

Swedish Flag Water Tower, 5211 N. Cark St.

Atop the Swedish American Museum is an iconic Chicago water tower that is painted to resemble the flag of Sweden — blue background with a bright yellow cross that is centered on the front facade. Constructed in 1927, the water tower has looked down over Andersonville for nearly a century. Damaged by snow and ice in 2014, the water tower was refurbished, rebuilt and remounted atop the Museum. Though it no longer functions as a water tower, it has regained its former role as one of the most noticeable attractions of Andersonville.

Lost Larson, 5318 N. Clark St.

When the Swedish Bakery, an Andersonville landmark, closed after more than 80 years in business on North Clark St., locals wondered where they might find their next lingonberry almond cake. They didn’t have to worry for long — enter Lost Larson, a bakery and cafe that more than fills the void left by the Swedish Bakery. Chef and owner Bobby Schaefer masterminds the treats, which range from cardamom-scented chocolate croissants to calamansi meringue tarts. Savory, open-face sandwiches topped with fresh produce and quality meats are also available.

Simon’s Tavern, 5210 N. Clark St.

Open since Prohibition ended (1934), Simon’s Tavern has built its reputation by serving glogg, a traditional Scandinavian mulled wine during the winter and a “slushy” version of it during the summer months. The interior of the bar is worth noting. There’s a neon fish drinking a martini, Viking paraphernalia, ancient Schlitz advertising and Swedish artifacts and treasures from the surrounding neighborhood.

Women and Children First Bookstore, 5233 N. Clark St.

Women and Children First is one of the nation’s largest feminist bookstores stocking more than 20,000 books by and about women, children’s books, and a wide-ranging collection of LGBTQ literature. First opened in 1979, the store strives to offer an environment where “everyone can find books reflecting their lives and interests in an atmosphere in which they are respected and valued.”

Ebenezer Lutheran Church, 1650 W. Foster

This beautiful church was constructed in 1902 by a rapidly-growing congregation of Swedes who lived in and around the Andersonville neighborhood. The altar, considered by Chicago artists and architects to be one of the most perfectly balanced works of its kind, includes two magnificent carved stone doorways and art glass windows that feature scenes from the life of Christ.

Rosehill Cemetery, 5800 N. Ravenswood Ave.

Located on a beautiful 350-acre North Side site, Rosehill is the largest cemetery in the City of Chicago. The front gate to the cemetery was designed by William W. Boyington, the architect of the old Chicago Water Tower, and was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1975. Rosehill is the final resting spot for a number of well-known Chicagoans, including broadcaster Jack Brickhouse, advertising executive Leo Burnett, meat industry executive Oscar Mayer and retailer Aaron Montgomery Ward.

Chicago Greystones, 1400-1500 W. Berwyn

Greystones are residential units constructed out of limestone from South Central Indiana that gives the home a distinctive grey, castle-like feel. They are relatively common in Chicago (more than 30,000 of them) but are scarce in other parts of the country. Most of the housing units are built either as single-family townhomes, a two-flat or a three-flat. In Chicago, the first greystones were built in the 1880s (a decade after the Chicago Fire) because the city’s new fire code banned wood construction — making them an ideal housing unit for the city. Andersonville is home to many Chicago greystones which can be seen on a number of residential streets throughout the neighborhood, including west Berwyn St.

Hopleaf, 5841 N. Clark Street

Opened in 1992, Hopleaf is a relaxed, no-nonsense tavern offering 68 types of craft beer, fine wines, spirits and cocktails, cider and meads. About 15 years ago, Hopleaf began to offer thoughtfully sourced, in-house prepped, chef-inspired dining and effectively turned itself into one of the nation’s first gastropubs. It wasn’t long before it earned a listing in the Michelin Guide. Hopleaf’s website describes the atmosphere of the gastropub: “Lacking screened distractions, games or live entertainment, Hopleaf is for drinking, eating and talking with friends, new and old.”

Edgewater Historical Society, 5358 N. Ashland Ave.

Edgewater is a large community on the north side of Chicago that encompasses Andersonville and two other neighborhoods — Lakewood Balmoral and Bryn Mawr. Located in a renovated firehouse in Andersonville, the Edgewater Historical Society is a museum that collects and preserves the history of local residents, businesses and local organizations. It contains a wide range of live and virtual exhibits, including retrospectives on the gone-but-not-forgotten Edgewater Beach Hotel, Sheridan Road, and the fluctuating water level of Lake Michigan (and its impact on Chicago’s shoreline).

Chicago Magic Lounge, 5050 N. Clark St.

Opened in 2015 in Andersonville as an homage to the close-up magic bars and restaurants of the 1930s and 40s, this retro-styled venue features strolling magicians who perform close-up card tricks and other illusions tableside for customers. The Magic Lounge also has several small theaters that showcase touring magicians and related mystical entertainment.

Andersonville Galleria, 5247 N. Clark St.

The Andersonville Galleria is a retail market building that features over 100 vendors offering apparel, jewelry, artwork, home furnishings, giftware, accessories, antiques, fair trade and gourmet treats. It’s like a combination indoor art festival and outdoor flea market.

Philadelphia Church, 5437 N. Clark St.

Built in 1921 as the Capital Savings Bank, the financial institution didn’t survive the Great Depression. In 1939, the building was purchased by the Swede-influenced Philadelphia Church whose mission was and still is “to bring people to Jesus Christ and to fellowship in the church body.” A huge, 1940-ish neon sign over the front door that reads “Jesus Saves” steals the show. When lit, it is one of the most picture-worthy shots in all of Chicago.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we’re currently running! L Stop Tours operates unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Its own city

For 106 years, the Chicago Union Stock Yards and adjacent meat packing plants were the most dominant businesses on Chicago’s South Side.

The Stock Yards complex was a veritable city unto itself — a 450-acre tract of land with 10,000 livestock pens with a capacity of tens of thousands of animals; hundreds of smoke-belching meat packing and rendering plants; a large post office dedicated primarily to Stock Yards workers; fully functional fire and police departments; an upscale hotel and world-renowned restaurant (the Stock Yard Inn); and a cavernous indoor stadium (the Chicago Amphitheatre), which hosted livestock shows, presidential nominating conventions and even the debut season of the Chicago Bulls (whose nickname was derived from the neighborhood’s most abundant commodity).

The Stock Yards District also was home to “Whiskey Row,” approximately 75 bars and taverns that were crammed into a one-mile stretch of South Ashland Ave.; more than 150 miles of railroad track that crisscrossed the neighborhood like steel mesh; and its own dedicated elevated transit line — the “Stock Yards Branch” — which featured stations that were named after meat industry names and businesses, such as Packers Ave., Exchange Ave., Swift and Armour.

While the Stock Yards withstood many challenges during its eleven-decade existence — several horrific fires, labor unrest, economic depressions, political pressure and ever-tightening food and safety regulations — the facility finally fell victim to a force it could not stop, the decentralization of the nation’s livestock and meat industries. Chicago’s meat packers simply closed shop and moved west to be closer to the supply of livestock. As a result, the Stock Yards no longer were needed as a marketing center. On July 31, 1971, the huge facility closed its famous front gate for the last time — it was the end of an era for one of Chicago’s largest and most important industries.

What’s there now?

Today, more than 50 years after its closing, there are very few remnants of the livestock or meat packing industries on Chicago’s South Side. The entire complex (livestock pens, packing plants, railroad shipping facilities) has been bulldozed — replaced by a massive development called “Stockyards Industrial Park,” an assortment of warehouses and manufacturing plants that are engaged in virtually every type of business other than meat packing. Nearby retailers no longer identify their shops with special neighborhood monikers (i.e. Stock Yards Hardware, the Yards Coffee Shop, etc.); and even that smell, that pungent, odoriferous, godawful smell that permeated every square inch of the South Side (and often the entire city), is gone.

Is anything left from Chicago’s glorious past as the livestock and meat packing capital of the world? Yes, but you have to know where to find it. That’s where we come in.

Welcome to L Stop Tours’ Self-Guided Tour of Chicago’s former Stock Yards and Meat Packing District.

Bubbly Creek

South Branch of the Chicago River near Ashland Ave. to W. 38th St.

This infamous one-mile stretch of waterway served as a dumping ground for waste materials from the city’s meat packers (blood, entrails, etc.) during the first 50 years of the Stocky Yards existence and was brought to everyone’s attention by Upton Sinclair in his novel, The Jungle. The Creek’s name is derived from small gas bubbles that regularly burst on the surface of the Creek — a byproduct of the, uh, byproducts in the water for all these years. Today, the waterway is much cleaner than it was in Sinclair’s day and the channel is suitable for boating or fishing. On a hot day, if you take a close look at the surface of the water from one of the area’s bridges, you can still see bubbles rising to the surface.

Live Stock National Bank

4150 S. Halsted

Built in 1925, this beautiful Colonial Revival-style building is a survivor. A replica of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, the bank outlasted the Great Depression, Chicago’s gangland wars of the Roaring ’20s and the horrific Stock Yards fire of 1934 (the bank opened for business the next day). The interior of the building was not what you would expect for a bank that mostly did business with blue collar meat plant workers, cattlemen and neighborhood residents — it was opulent, with chandeliers, plenty of marble, classical moldings, raised panels and fluted pilasters. The bank closed in 1965, six years before the Stock Yards would cease operation. Although many efforts have been initiated to redevelop the building over the years, none have made it the finish line. The building stands today on the northeast corner of Halsted and Exchange — empty and boarded up — waiting for someone to restore its former prominence.

Stock Yards Gate

Exchange Ave. at Peoria St.

Erected in 1875, this limestone gate, designed by renowned local architect John Welborn Root, stands today as one of the few visual reminders of Chicago’s past dominance in the livestock and meat packing industries. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1981, the gate marked the eastern entrance to the vast 475-acre Stock Yards, the largest facility of its kind in the world. Directly behind the gate is a memorial to Chicago Firefighters who died in the line of duty, especially those who perished in the Stock Yards Fire of 1934.

Stanley’s Tavern

4258 S. Ashland Ave.

The history of Chicago’s Stock Yards is interwoven with characters from the neighborhood who, like the Yards themselves, were long time survivors. Stanley’s Tavern is the last saloon still operating on Whiskey Row, the infamous stretch of Ashland Ave. between Pershing Rd. and W. 47th St, which housed dozens upon dozens of bars for thirsty Stock Yards employees, meat packing workers and neighborhood residents. Though Whiskey Row dates to the early days of the Stock Yards (1865), Stanley’s has an equally impressive history and has been serving loyal customers in the same location since 1935.

Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council

1823 W. 47th St.

Just southwest of the Stock Yards, Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood has long served as a beacon of light for immigrant workers seeking opportunity —jobs in livestock and meat packing industries and affordable nearby housing. Over the years the Back of the Yards neighborhood has been among the most ethnically diverse areas of the city — among the first arrivals were the Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, then the Slovaks, African Americans and then Mexican Americans. Formed after the Great Depression, the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council is an organization whose mission is to “enhance the general welfare of all residents, organizations, businesses in our service areas.” It accomplishes this with social service and economic development programs that support the community. The Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council stands today as a reminder that neighborhoods and community organizations often outlive the businesses and industries that once were responsible for their birth and existence.

Swift Mansion

4500 S. Michigan Ave.

This ornate, Richardsonian Romanesque gray stone mansion was built in 1892 as a wedding gift to Helen Swift, the daughter of Gustavus F. Swift, the founder of Swift & Co. and also the inventor of the refrigerated rail car (for shipping meat carcasses long distances). Interestingly, Helen Swift married Edward Morris, the son of another large Chicago meat packer, Nelson Morris. The Morrises lived in the home until 1916 when they moved to another they built on nearby Drexel Ave. After serving as a residence for other families, the mansion was a funeral home and most recently was occupied by the Urban League and the Inner City Youth and Adult Foundation.

Stockyards Industrial Park

located in an area bounded by Pershing Road, Halsted Ave., W. 47th St. and Ashland Ave.

There is life after the Stock Yards, particularly in terms of the Stockyards Industrial Park, a collection of about 100 businesses (warehouses, manufacturing plants, offices) that have been built on the former Stock Yards property in the 50 years since the huge livestock facility closed. The Industrial Park is clearly marked — huge metal, gate-like structures with “Stockyards Industrial Council” inscribed on circular medallions arch over neighborhood streets, marking the boundaries and major arterials running through the park. Without these signs, it is virtually impossible to detect that the Stock Yards once stood here.

Railroad Tracks

3950 S. Morgan

The railroads played a leading role in the success of the Union Stock Yards over the years. Livestock-hauling freight trains brought hundreds of millions of animals Chicago annually from all parts of the country and refrigerated railroad cars (invented by meat packer Gustavus Swift in 1875) enabled meat carcasses to be shipped as fresh product back to those very same parts of the country that the livestock came from, and farther. Railroads were the transportation vehicle of choice until the 1950s when trucks made the process more efficient and economical. Though many of the railroad tracks that snake through the district are abandoned, some, including this set of tracks on Morgan St. are still active and in use.

Kent House

2944 South Michigan Ave.

Designed in 1883 by the prominent architectural firm of Burnham and Root, this lovely Queen Anne mansion was built for Sydney A. Kent, one of the founders of the Chicago Union Stock Yards and survives as one of the few remaining mansions on this former upscale stretch of South Michigan Ave. Recently converted into several condominium apartments, the building was designated a Chicago landmark in 1987.

Stock Yards L Branch

State Street and West 40th Street

In 1908, the South Side Elevated Railroad took over a little-used 2.8-mile railroad line running west from the Indiana Avenue Station (today’s Green Line) and extended it to the Stock Yards where it went around a big loop and headed back toward Indiana. The Stock Yard Branch, as it was called, was popular with the 50,000 area workers as well as tourists who would take the L from downtown to visit the huge Stock Yards complex. The Chicago Transit Authority, which assumed control of Chicago’s public transit system in 1947, discontinued operations on the line in 1957 due to declining ridership. This remnant of the elevated line (a “severed” overpass on State Street near West 40th Street) reveals where the former elevated line used to run.

Vienna Beef

1000 W. Pershing Road

One of Chicago’s most prolific and popular meat companies, Vienna Beef, which got its start when its founders sold hot dogs at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, never had a manufacturing facility located anywhere near the Stock Yards or Packingtown…until 2013. That’s when the Chicago-based company moved its manufacturing facility from its long-time North Side location to its present site on the northern edge of what is now Stockyards Industrial Park. While other meat packing plants and food manufacturing facilities have long-since vacated the South Side and Stock Yards District, Vienna Beef stands today as one of the few actual meat companies that still operate within the former Stock Yards district — even though it is a relative newcomer to the neighborhood.

Packers Avenue

1300 west for 6 blocks from 4000 south to 4600 south

Today, Packers Avenue is just another street sign that labels a non-descript roadway in an industrial park. Over 100 years ago, the largest meatpackers in the world lined this street, which got its name from the businesses that operated here. Another area street, Exchange Avenue (runs west at 4150 S. Halsted), is named after the Exchange Building of the Union Stock Yards, an office building where the paperwork for all live animal transactions was completed.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Día de los Muertos

Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a holiday that’s just around the corner and the Chicago neighborhood of Pilsen is one of the best spots in the city to commemorate it. Typically, Día de los Muertos is celebrated on Nov. 1-2 to coincide with All Saints Day and All Souls Day. Historically, it is a time when Mexicans celebrate the lives of their ancestors.

What is it?

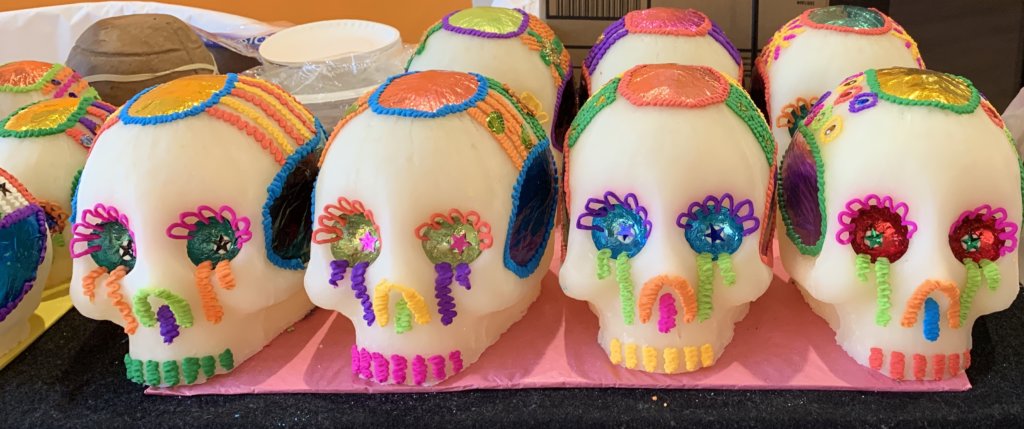

By no means a somber occasion, Día de los Muertos is a celebration of death and life with many bright and colorful traditions. Ofrendas, or offerings, are small, altar-like displays consisting of flowers, candles, photographs, clothing mementos and certain foods or drinks that are designed to welcome the spirits of the dead back to earth. Calaveras, or sugar skulls, are decorated replicas of human skulls that are made out of sugar or clay. They are used to remind the living that life is short and that it’s OK to poke fun at death. Finally, Pan de Muerto is sweetened, softened bread shaped like a bun that is decorated with bone-like designs and eaten as a tribute to the dead at gravesites or ofrendas.

Ofrenda at the National Museum of Mexican Art

What’s going on in Pilsen?

In Pilsen, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood just southwest of Chicago’s Loop, ofrendas, calaveras and Pan de Muerto are a major part of celebrations throughout the area — in homes, churches and at numerous special events.

The Pilsen-based National Museum of Mexican Art (1852 W. 19th St.) is hosting a huge community event that is also being held to support ongoing programming at the museum. The “Día de los Muertos: Love Never Dies Ball,” Saturday, Nov. 2 from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., is a special celebration that honors life and spirits of los muertos and will feature live music, culinary treats, beverages and a chance to win prizes.

Sugar Skills or Calaveras

In addition, the Museum also is celebrating with an event called “Día de los Muertos Xicágo” in Harrison Park (the park in which the museum is located) on Sunday, October 27th from 3 p.m. to 8 p.m. It will feature ofrendas, live musical performances, face painting, art activities and, of course, Pan de Muerto. It is a family-oriented event and admission is free.

More to Check Out!

Furthermore, athletically-inclined individuals might consider signing up to run in the Carrera de los Muertos/Race of the Dead 5k. This race snakes through the streets of Pilsen and takes runners past many of the neighborhood’s fascinating murals. Runners are cheered on with live mariachis, traditional folkloric dance groups and spectators who are decorated and costumed in Día de los Muertos attire (as are many runners). The race begins at 8 a.m. on Saturday, Nov. 2 at Benito Juarez Community Academy, 1450-1510 W. Cermak Rd.

Have a sweet tooth? Dulceria Lupitas, (1730 W. 18th St)., is a throw-back candy shop with a wide range of delicious and inexpensive candy. Like spice? Many of their candies are dusted with chile powder for an extra burst of flavor. In October and November, the shop offers sugar skulls (calaveras) for those who wish to celebrate Día de los Muertos.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

I lived in Old Town for a couple of years in the early 1980s.

My wife and I lived in a two-bedroom apartment on Crilly Court, a one-block street just west of Wells Street between Eugenie and St. Paul Streets (the 1700 block). We lived on the first floor of a building built by developer Daniel Crilly in 1877, six years after the Great Fire. The four-story apartment building (now condos) was not only historic, it was distinctive — Crilly had the names of his four children (Oliver, Isabelle, Edgar, Erminnie) sculpted in stone above four of the building’s doors. We lived in the Erminnie section.

I have a lot of fond memories — and some not so fond — of living in that apartment in Old Town. There was the time we decided to host a throwback 1960s party and several hundred people showed up, including a sports anchor from CBS channel 2 that no one knew; the time we filled the apartment with smoke because we forgot to open the fireplace flue; and the time I spent about three hours “defrosting” on a radiator near the front door after a brutally cold 3-degree Bears game.

The best part about living in Old Town, however, was walking around and exploring the neighborhood. There were so many interesting shops, restaurants, taverns and entertainment venues that it was often difficult deciding where to go or what to do. So many options, so little time.

Nearly forty years later, as I look back on my days in Old Town, I find it incredible that many of the places that my wife and I used to haunt are not only still in business, they are thriving. In the spirit of bridging the past with the present, I have compiled a list of Old Town business establishments that we used to visit (in the 1980s) that are still going strong today.

Iconic Old Town Chicago Spots

Second City

In the early 1980s, Second City only featured shows on the main stage, there were no second- or third-level improvisation shows on different stages as there are today. We used to go to the box office early on Saturdays because they would sell remaining tickets for that evening’s show at half price. But you had to be there in person to get tickets and only during a short time window in the middle of the day. Because we lived only about a block away, it was not a problem for us to get in line regularly on Saturdays. Today, thanks to the Internet and an expanded platform of shows at Second City, it’s easy to get full-fare or discounted tickets without ever leaving your home.

Twin Anchors

The baby back pork ribs at Twin Anchors were legendary forty years ago when we first ate there and they are every bit as iconic today. Add to that the cool retro ambiance of this 87-year-old tavern and you’ve got the makings of a neighborhood “joint” that was, is and always will be a Chicago classic. For its longevity and exceptional service to the city and its residents, Twin Anchors should become the fifth red star on Chicago’s municipal flag.

Nookies

Everyone has a favorite breakfast place and we had ours, Nookies on Wells Street. Actually, we had two favorites but the other one, Original Mitchell’s, at the corner of Clark and Wells, is no longer a survivor — it closed several years ago and is therefore disqualified from being in this review. Nookies, on the other hand is a stalwart, and now has three other restaurants on the North Side. What we knew as a small breakfast café/diner has grown into a full restaurant that also serves lunch and dinner. Doesn’t everyone always enjoy an expanded offering of Nookie(s)?

Zanies

Occasionally, when we couldn’t procure half-price tickets at Second City, we would venture over to Zanies on Wells, just south of North Ave. Founded in 1978, Zanies specializes in stand-up comedy and has hosted just about every big time comic you can think of when they were in their formative years, such as Jay Leno, Tim Allen, Jeff Garlin, Chris Rock, Dave Chappelle, Gilbert Gottfried, Chelsea Handler and many more. Though there were many comedy clubs competing for our dollars in the 1980s, Zanies is the only comedy club in Chicago today that is programming stand-up comedians seven days a week.

Fudge Pot

Back in the day, I had three reasons — and three reasons only — for going to the Fudge Pot, a neighborhood candy store that has been on Wells Street since 1962. Either I was looking for a unique or last-minute gift, I was looking for something that I couldn’t find at other stores, or I simply had to satisfy my sweet tooth. Frankly, reason number three occurred far more frequently than the other two. Go figure. Today, whenever I’m near Old Town Chicago, my sweet tooth begins to throb like a pulsating boombox and my car begins to veer toward the Fudge Pot like its being pulled by a giant magnet. Fortunately, today’s Fudge Pot is bigger and better than ever with more candy and sweets than you can possibly imagine. You can also watch them make the candy — all the equipment and work tables are fully visible to anyone who walks into the shop.

House of Glunz

In the early years of our marriage, my wife and I realized we had a lot to learn about wine and spirits before we could confidently serve said liquor to family or friends that were visiting us in Old Town Chicago. Fortunately, we discovered the House of Glunz, a legendary Old Town liquor merchant that has been serving Chicagoans since 1888. The staff took time to educate us and were very helpful. It’s still in the same location today. Let’s face it — you don’t stay in business for 131 years unless you’re doing something right.

Old Town School of Folk Music

The legendary Earl of Old Town, a nationally-acclaimed venue for folk music, vanished from the scene more than three decades ago but the Old Town School of Folk Music, the educational center of the profession, is now in its 62nd year of operation is still going strong. When I lived in Old Town, I once came dangerously close to taking bagpipe lessons at the School (are the bagpipes considered folk music?). Fortunately, I was talked out of it by my calm, collected and tone-deaf wife. From classes to concerts to shopping for music products in their store, the School of Folk Music is truly a unique Chicago institution. No longer located in Old Town, the School now has facilities in Lincoln Park and Lincoln Square.

Additional Places to Check Out if You’re in the Neighborhood of Old Town Chicago:

- Old Town Oil – a cute shop that sells oil and vinegar you can taste. Aged vinegar is surprisingly sweet!

- Topo Gigio – an Italian restaurant with excellent food and wine as well as a large patio to enjoy during the warmer months

- Old Town Ale House – A popular dive bar and favorite among locals that was established in 1958

- Old Jerusalem – Family-owned middle eastern restaurant with fresh food and pastries

- Happy Camper – a vibrant pizza place and bar filled with camping decor

- Cocoa and Co – a chocolate shop with candies and drinkable flavored chocolate

- La Fournette – an authentic French bakery and cafe to relax and enjoy a coffee and snack

- The Spice House – a spice store with every kind of spice and mixture you can imagine,

including blends that are representative of Chicago¹s neighborhoods

There’s lots to see in the Old Town Chicago neighborhood. Interested in learning more? See these fascinating sites, and many othres, on L Stop Tour’s Brown Line tour.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

What To Do in The Loop

The Loop is one of Chicago’s 77 community areas. It is named for the elevated trains that form a loop over the streets. The area extends beyond the actual train loop, however. Within the area are several neighborhoods and districts including Printers Row, Jewelers Row, and the Theatre District. In addition, the area was also once home to the world’s first skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building.

In recent years, new growth and development have started attracting more tourists and locals. Beyond the usual tourist attractions, The Loop has a lot to offer.

Things to Do

Stroll Lakefront Trail — Walk, skate, scoot or pedal Chicago’s 18.5 mile trail along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

Hang out on the Riverwalk — Enjoy shops, restaurants, taverns and more on this 1.25-mile walkway along the south bank of the Chicago River.

Ride the Water Taxi — the Water Taxi picks up along the Chicago River and takes visitors to several neighborhoods including Chinatown. Find the schedule here.

Check out Millennium Park — Music, sculpture, gardens, fountains and more await you at this urban oasis located at Randolph St. and Michigan Ave.

Visit the Art Institute —Visit what is regularly rated as one of the top art museums in the world.

See Buckingham Fountain —Beautiful by day, even more beautiful at night with a spectacular 20 minute light and music display every hour on the hour.

Peek into the Harold Washington Library — In addition to the usual library resources, this “new” library (built 1991) contains a wide variety of interesting exhibits, archives and a beautiful Winter Garden on the ninth floor.

Check out The Cultural Center – This building houses the largest Tiffany Dome in the world along with many other exhibits.

Visit the Gene Siskel Film Center — A center for film enthusiasts with more than 1,500 screenings and 100 guest artist appearances annually.

Visit the American Writers Museum — A unique museum of American literature and writers that opened in 2017.

Bars/Restaurants

London House – Enjoy a cocktail and a spectacular view of Chicago from the rooftop terrace on the 22nd floor of the London House Hotel.

Cindy’s – Dine, sip beverages and enjoy the view from the outside balcony at Cindy’s, located on the top floor of the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel.

The Game Room – Also located in the CAA Hotel, this bar offers many games such as shuffleboard, chess and foosball along with drinks and snacks.

Buddy Guy’s Legends – Eat, drink and enjoy the blues at the club of one of Chicago’s true originals, Buddy Guy.

Miller’s Pub –Serving American cuisine, pub food and cocktails to Chicagoans since 1935.

Morton’s The Steakhouse – Steakhouse restaurant (now a chain of restaurants) founded by legendary Chicago restaurateur Arnold Morton.

Prime and Provisions – A vibrant and modern steakhouse drawing inspiration from 1920’s supper clubs.

The Berghoff – A Chicago tradition serving authentic German food and drink to patrons since 1898.

Trattoria #10 — Classic Italian food in an intimate, elegant setting; it is popular with the theatre-going crowd.

Catch 35 — High-end Chicago restaurant focuses on seafood but also has steaks, salads and bar food on the menu.

Monk’s Pub – A decades-old pub with craft beer and pub fare.

AceBounce – A Ping Pong Bar and Restaurant were guests can rent tables in 30-60 minutes increments and enjoy cocktails.

Now that you know what to do in the loop, make your reservation with L Stop Tours and see Chicago like Chicagoans!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.