– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the most frequently asked questions about the L and want to learn more about the city and its history, then consider signing up for our blog newsletter!

I spend a lot of time on the L.

Our tour company, L Stop Tours, utilizes Chicago’s elevated transit system to visit unique, culturally-diverse neighborhoods throughout the city. On every tour, we tell our guests as much as we can about the L — how it came to be, the size and reach of the system, how it has evolved over time, and so on — but our guests always seem to have more questions. Like many people, they are fascinated by the L and want to know more.

Below is a list of the most frequently asked questions we receive about the L:

How big is Chicago’s rapid transit system?

With 1,492 rail cars operating on eight routes, 224 miles of track, and nearly 230 million passengers transported per year (pre-pandemic), Chicago’s rapid transit system is the second-largest and second busiest system in the U.S. The most heavily-traveled route on the system is the Red Line, which carries 252,000 passengers on an average weekday (pre-pandemic). Another interesting fact, Chicago is the only major U.S. city to have an elevated system serving its downtown area.

How old is Chicago’s L?

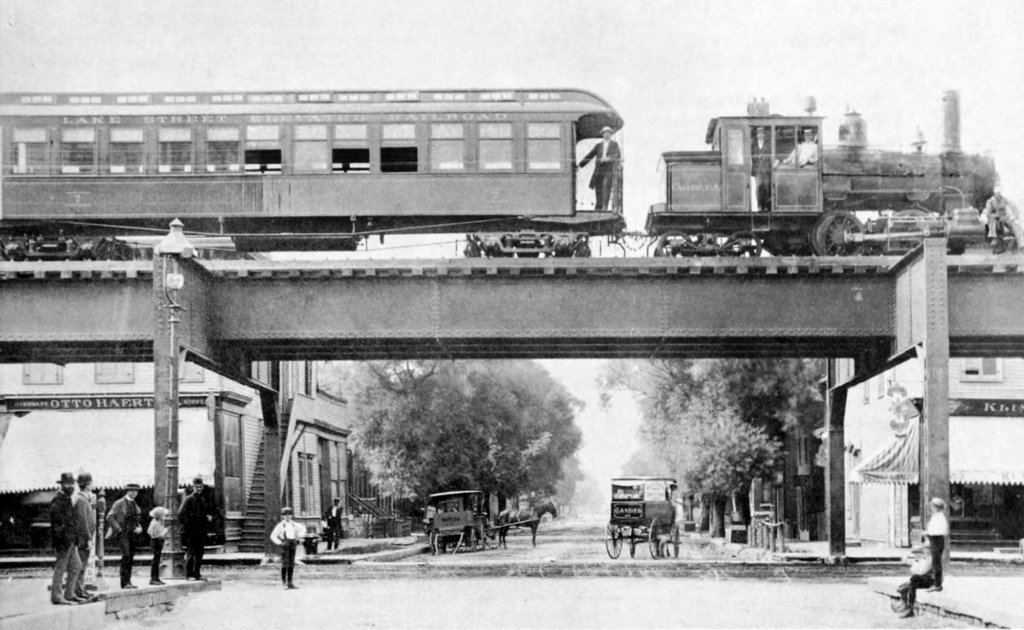

The city’s first elevated rail line, constructed by the privately-owned Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad, began transporting passengers on June 6, 1892, on a four-mile stretch of track between Congress Avenue just south of downtown and 39th St. The service, a small steam locomotive that pulled four wooden nuecoaches, was an immediate hit with locals and was extended another four miles the following year to accommodate visitors attending the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Jackson Park. Three other privately-owned elevated transit lines were built in the next three years — the Lake Street Elevated Railroad, the Metropolitan West Side Railroad and the Northwestern Elevated Railroad.

When did the L system go electric?

In 1895, the Metropolitan West Side elevated line was the third L company to begin rapid transit operations in Chicago but the first to use electricity to power its trains. Two years later, the South Side L introduced multiple-unit control in which the operator can control all motorized cars in a train, not just the lead car. Shortly thereafter, the remainder of the lines switched to electric service. Interestingly, electricity and multiple-unit control remain standard features on most of the world’s current rapid transit systems.

How did Chicago’s Loop get its name?

When Chicago’s first elevated lines went into operation, none were allowed to provide service in the downtown area — property owners felt the system was ugly and that it would reduce property values. A wealthy financier, Charles Tyson Yerkes, thought otherwise and was able to convince property owners that an elevated transit system would bring more people downtown and would be good for business. Finally, the property owners agreed and Yerkes built what he called the “Union Loop,” a 1.79-mile closed circle that connected all of the city’s privately-owned elevated railroads into a common system. Over the years, the term “Loop” has come to refer to Chicago’s original downtown area, or more precisely, any property that is located inside the Loop elevated structure (an area bounded by Lake Street on the north, Wabash Avenue on the east, Van Buren Street on the south and Wells Street on the west).

Why did Chicago decide to elevate its transit system while other cities used subways?

Chicago’s resolve to rebuild itself after the Great Chicago Fire resulted in an unprecedented period of growth and expansion for the city — between 1872 and 1900, Chicago was one of the fastest growing cities in the world. As a result, pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages and streetcars converged to create gridlock on downtown streets — city fathers knew that a new transit system was badly needed. Although subways were the choice in other growing cities like New York and London, Chicago selected elevated railways because they were cheaper to construct and did not require much digging (there were concerns at the time that the city’s swampy soil might not tolerate a subway system).

When and why did the Chicago Transit Authority come into existence?

In 1924, all of Chicago’s original L companies were combined into a new private entity, the Chicago Rapid Transit Company, in order to facilitate better cooperation among the lines. Following World War II, Chicago and Illinois officials decided that all bus, streetcar and rapid transit lines should become publicly-owned. In 1947, the newly established Chicago Transit Authority assumed control of all transportation systems within the City of Chicago.

Chicago built two subways, not elevated lines, many years after the elevated system was well established. Why?

The State Street subway, a 5-mile segment in the middle of today’s Red Line, went into operation in 1943 and the Dearborn Street subway, serving the Blue Line downtown, was completed in 1951 Both of these service expansions were built as subways in order to minimize train traffic on the Loop tracks and to speed passenger travel through the downtown area. To this day, trains on the Red and Blue lines descend from elevated tracks just outside the Loop into the subways in the downtown area (35 feet below ground), make several stops, and ascend to elevated tracks after emerging from the downtown subway.

Why are there no public restrooms at CTA stations?

The CTA used to have public restrooms at most stations but closed them in the 1970s. (These restrooms are now locked and available only to CTA employees and/or passengers with an emergency medical condition.) The reason? According to the CTA, public restrooms require significant resources to maintain and keep secure — and the CTA does not have the resources to maintain these facilities or keep them secure at a high enough level for the general public.

Does the CTA ever use old rail cars for regular service?

Not for daily or regular service, however, the CTA maintains a small fleet of vintage rail cars, the Heritage Fleet, that is used for charters or special events in which the public is invited. Additionally, Chicago L car number one — the very first car used on the L tracks (1892) — is on permanent display at the Chicago History Museum. Visitors to the museum are invited to step aboard the car and look around.

Is it the “L” or “el?”

Both the CTA and the four original privately-owned transit companies always referred to their trains as the “L,” meaning that the nickname (short for elevated railway) dates back nearly 130 years. It is thought that rapid transit operators in Chicago preferred “L” because it was different from elevated service in New York City. which went by the nickname “the el.”

Why are Chicago’s rapid transit cars shorter than those in other cities?

Chicago’s transit vehicles are shorter in order to better navigate the sharp turns in the Loop, such as Adams and Wabash and Wells and Van Buren. And while Chicago’s rapid transit system is the second busiest in the United States, its shorter cars (48 feet versus New York’s 51 feet) comfortably handle its ridership loads on a daily basis. In short, there is not a need for longer cars.

How much is a single ride on the L?

A single-ride train ticket — three rides within two hours of purchase — costs $3 (or $5 if purchased at O’Hare Airport). Riders can also utilize the CTA’s electronic fare program, Ventra, which offers a number of different fare and pass options that can be loaded onto the reusable card, as well as a cash balance or electronic payment options.

Are there any express trains on the CTA system?

The only scheduled express train service on today’s CTA system is the Purple Line, which skips a few stops on its way to and from Howard Street and the Merchandise Mart, cutting about 15 minutes off the normal 45-minute all-stop service one would encounter by taking Red and Brown Lines to either of these destinations. Years ago, the CTA utilized a skip-stop service on all of its routes (“A” and “B” trains that stopped at alternate “A” and “B” stops in order to speed transit times), but that service was eliminated in 1995.

Any expansion of the system planned for the future?

The Chicago Transit Authority is proposing to extend the Red Line from the existing terminal at 95th/Dan Ryan to 130th Street, subject to the availability of funding. The proposed 5.6-mile extension would include four new stations near 103rd Street, 111th Street, Michigan Avenue, and 130th Street.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

POPULAR TRIPS

Duration: 3.5 hours

Price: Adult $65

- Tour price includes transit fees. Food/beverages purchased by guests.

- Tour begins and ends in the Loop.

- Walking distance: 1.5 miles

Duration: 3.5 hours

Price: Adult $65

- Price includes transit fees. Food/beverages purchased by guests.

- Tour begins and ends in the Loop.

- Walking distance: 1.1 miles

Duration: 3 hours

Price: Adult $65

- Tour price includes professional tour guide, train ride. Food/beverages purchased by guests.

- Tour begins and ends in the Loop.

- Walking distance: 1.5 miles

NEWSLETTER

Stay in the LOOP and subscribe to our monthly newsletter today!