14 Things You Didn’t Know Were Invented in Chicago

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Although Chicago is commonly known as the “Second City,” it’s equally known as a city of “firsts.”

Unfortunately, we’re not referring to the success of local sports franchises. The “firsts” that we’re talking about are things that were invented in Chicago or the metropolitan area. Many of these inventions are celebrated widely in the media — the Ferris Wheel (1893 World’s Fair), deep dish pizza (Pizzeria Uno in 1943), the brownie (Bertha Palmer and the Palmer House, 1893), the world’s first modern skyscraper (Home Insurance Building, 1888) and Playboy magazine (Hugh Hefner, 1953).

Many of Chicago’s other firsts, however, are not as well known. So, in our never-ending quest to shed a spotlight on all things Chicago, we’ve compiled a list of lesser-known Chicago inventions or “firsts.” Here they are in no particular order:

Blood Bank

After observing the difficulties experienced by World War I soldiers who needed a certain blood type for a transfusion, Bernard Fantus, a Chicago physician came up with a better idea. He developed a method of blood preservation and storage that allowed patients to access blood without waiting for a donor. The nation’s first blood bank opened at Cook County Hospital in 1937.

Spray Paint

Although aerosol cans had been around for years, no one ever thought to fill the can with paint. In 1947, suburban Chicago resident Edward Seymour, at the suggestion of his wife, Bonnie, filled an aerosol can with aluminum-colored paint and pressed the button. The result was not only a smooth, evenly-coated painted surface, Seymour realized that he had now made painting easier and portable. Spray paint was an instant commercial success. In 1992, the Chicago City Council banned the sale of spray paint in an effort to crack down on graffiti.

Sleeping Cars on Trains

After a long, restless night on a train in 1862, George Pullman, a Chicago mechanical engineer, had the idea to create a luxury sleeping car for trains. The “Pioneer,” as he called it, had rubberized springs that reduced shaking, its walls consisted of dark walnut and the seats were covered with plush velvet. Silk window shades, crystal chandeliers and brass fixtures added to the overall feeling of luxury. At night, the seats unfolded into lower sleeping berths and an upper berth dropped down from a cabinet in the ceiling. To mass produce the railcars, Pullman created the Pullman Palace Car Company (on Chicago’s far South Side), which was responsible for other rail innovations like the dining car, the lounge car and the covered vestibule between passenger rail cars.

Car Radio

The first commercially successful car radio was designed and built in 1930 by Chicago’s Galvin Manufacturing Company. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Paul Galvin noticed that radios sales were down but car sales remained steady— owning a vehicle was still important to consumers, even in a poor economy. Galvin found a way to mount a radio in his Studebaker and drove it 815 miles to Atlantic City where the 1930 Radio Manufacturers Association Convention was being held. Upon arrival, he parked the car at the base of the pier and turned up the volume. The radio was a big hit, so Galvin returned to Chicago to begin manufacturing his product. On the way home he decided to give his product and company a new name — Motorola — a combination of “motor car” and “Victrola.”

Automatic Dishwasher

Automatic Dishwasher

Josephine Garis Cochran did not like having to hand wash dishes after entertaining friends and relatives at her home. She is claimed to have said, “If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself.” She partnered with a mechanic, George Butters, and created a machine that she showed at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago (1893). In addition to winning an award for its mechanical prowess and durability, it attracted considerable interest from restaurants and hotels, both of which saw the machine as a great way to become more efficient. Cochran’s Crescent Washing Machine Company became part of KitchenAid in 1913 through an acquisition by Hobart Manufacturing Company.

Soap Opera

After working as a staff writer at WGN in Chicago, former teacher Irna Phillips created a serialized daily program geared toward women, “Painted Dreams,” which was about a widowed matriarch of a large Irish-American family. The year was 1930, the medium was radio and the program aired for two years on WGN. Because her show often was sponsored by soap manufacturers, it became known as a soap opera. Prolific in her writing, Phillips also created other soap operas that aired on radio and television, including “Guiding Light,” “As the World Turns,” “Another World” and “Love is a Many Splendored Thing.”

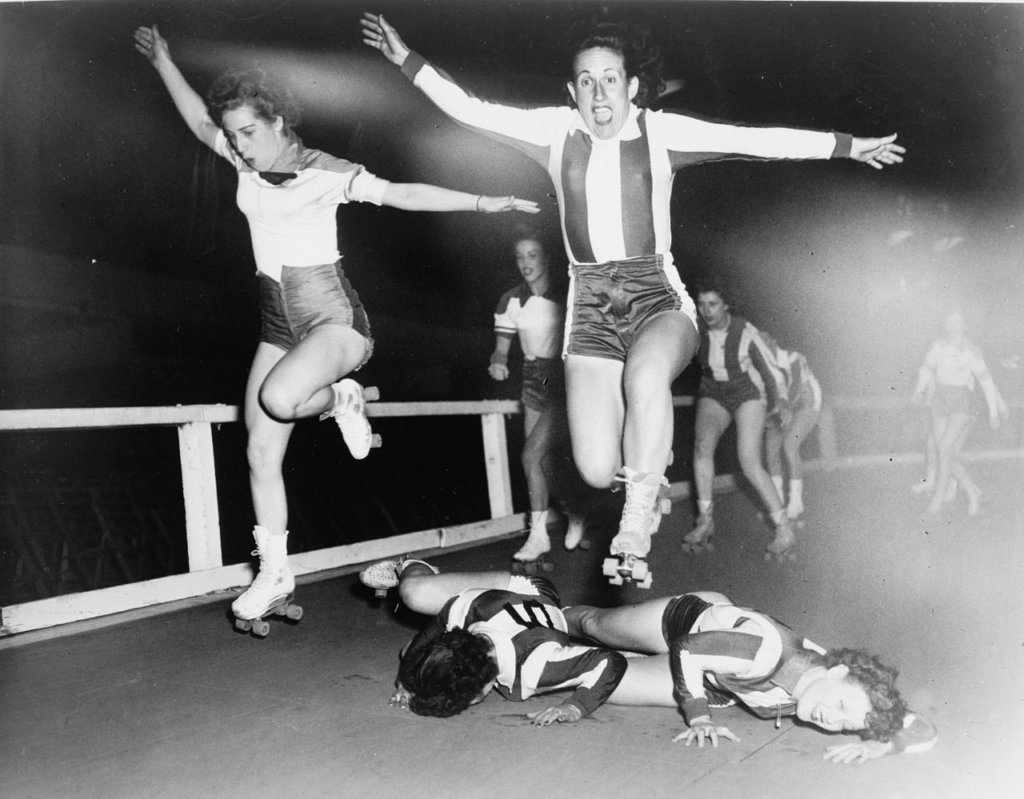

Roller Derby

Though roller skates were first introduced in London in 1735, the sport of Roller Derby was invented in 1935 by a Chicagoan, Leo Seltzer, an entrepreneur who was responsible for booking events at the old Chicago Coliseum just south of the Loop. For two years, the Coliseum hosted the “Transcontinental Roller Derby,” a multi-week event in which teams of skaters raced against one another on “trips” (miles that were tracked and plotted daily on maps) between large American cities, like Chicago to San Diego or New York to Salt Lake City. In 1937, Seltzer changed the rules to make the sport more exciting. Instead of long-distance races, teams scored points by breaking through and passing players on the opposing team. At 10 cents per ticket, Roller Derby was by far the cheapest sports ticket in town, an important consideration for those looking for an escape from the hardships of the Great Depression and a main driver of the sport’s rapid growth.

Vacuum Cleaner

Although a carpet-sweeping device was introduced a few years earlier, the first manually-powered vacuum cleaner was invented in 1869 by Chicago inventor Ives W. McGaffey. Though it required a certain amount of athleticism to operate (you had to turn a hand crank while pushing the device across the floor), the machines were commercially successful and sold for $25 apiece. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed McGaffey’s inventory, however, one of his original models currently resides at the Hoover Historical Center in North Canton, Ohio.

Farm Silo

In ancient Greece, farmers stored grain in huge pits in the ground. In fact, the word silo is derived from Greek meaning, “pit for holding grain.” In 1873, Fred Hatch of McHenry County, Illinois thought there had to be a better way. He built an above-ground “pit” with round walls made of wood — a structure that generally is acknowledged as the first modern silo. It was successful, too. The new silo on his farm was filled with green corn fodder, so much so that Hatch’s cows stayed fatter and gave more milk than they ever had before.

Chicken Vesuvio

No one is quite sure about the origin of this popular dish but many have suggested that it first appeared on the menu of Vesuvio Restaurant, 15 E. Wacker Drive, Chicago, in the early 1930s. Served with potato wedges, this dish features a half chicken that is sautéed with garlic, oregano, white wine, lemon juice and olive oil. Though the restaurant has long since faded into the darkness, the recipe lives on in a number of Italian restaurants throughout the Chicago area.

Mobile Phone

Building on his company’s earlier success with the car radio, color television and two-way walkie-talkies, Martin Cooper, an engineer at Motorola, produced the world’s first handheld mobile phone in April 1973 in Schaumburg, Illinois. In 1983, the company launched its first retail mobile phone — the DynaTAC 8,000X. The handset (a phone only, not a smartphone!) offered 30 minutes of talk time, six hours of standby and could store 30 phone numbers. Its price, $3,995, was a little prohibitive by today’s standards.

The Wienermobile

In 1936, when Oscar Mayer Company was headquartered in Chicago, Carl Mayer, nephew of company founder Oscar, had an idea — a 13-foot-long hotdog mounted on a car that would travel the streets of Chicago promoting the company’s iconic brand. General Body Company of Chicago designed the first Wienermobile, which featured open cockpits in the center and rear of the vehicle. Today, a number of vehicles comprise the Wienermobile “fleet,” all of which can serve fully prepared Oscar Mayer hotdogs on location. The fleet consists of the full-size Wienermobile, a Mini Wienermobile (a hotdog on the body of a Mini Cooper), a motorcycle with a hot dog sidecar, and the Wiener Rover and the Wiener Drone, two remote-controlled hotdog delivery vehicles.

Twinkies

Twinkies were invented in Schiller Park, Illinois on April 6, 1930 by James Dewar, a baker at Continental Baking Company. When Dewar saw machines used to make filling for strawberry shortcakes idled when strawberries were out of season, he came up with the idea to develop a snack cake filled with banana cream to increase the machines’ utilization. A co-worker called the product a “Twinkie” after having seen a nearby billboard advertising “Twinkle Toe Shoes.” When World War II caused bananas to be rationed, the company switched the filling to vanilla, which proved to be even more popular than the original.

Zipper

A Chicagoan, Whitcomb Judson, is generally credited with inventing the first clothing fastener in 1891. Used mainly on shoes and boots, the device utilized a chain-lock mechanism that held leather together without separating. In 1893, Judson exhibited his invention at the Chicago World’s Fair. The device enthralled fairgoers, leading him to launch the Universal Fastener Company in Chicago to manufacture his product. The chain-lock device never achieved commercial success, however, the clasping device was used by Judson and other inventors as a springboard to create new and improved fasteners that closely resemble the “zipper” that is commonly used today.

Interested in the World’s Fair of 1893? We recommend a classic Chicago tale, The Devil in the White City. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the history of Chicago and want to learn more about the city and its history, then consider signing up for our blog newsletter!

From “ghost” voters to dirty tricks, vote stealing to intimidation tactics, Chicago elections chicanery has, over the years, become nothing short of political sport. Messing with elections — in some way, shape or form — is what we do. It’s known as the “Chicago way.”

But not, apparently, during the 2020 presidential election. With voter turnout at an all-time high and extra attention focused on the integrity of the voting process at post offices, polling places and vote counting centers nationwide, officials proclaimed the 2020 election as one of the “cleanest” in decades; that “fraud” was virtually non-existent. In fact, turnout was so high, I didn’t even need to wear my “Two Ballots Please, I’m From Chicago” button like I did in the 1988 presidential election. I felt naked without it.

Such honesty and cleanliness is enough to make an old, died-in-the-wool Chicago election watcher (like myself) nostalgic for the days when Chicago elections featured daring fraudulent behavior and political hijinks. That said, here are some “Great Moments” in Chicago election history:

- Follies of 1856

- Deafening Support

- Election Insurrection

- Idenitfying Judas

- An Explosive Victory

- Beat the Press

- Don’t Mess with the Machine

- Quote for the Ages

- Stealing Home

- Simple Math

- Actually Seeing a Few “Ghosts”

- A Man of Conviction

Follies of 1856

Chicago Mayor Thomas Dyer is defeated in his re-election campaign by Democratic Congressman “Long” John Wentworth in a landslide. It became evident during the Chicago elections that voters never forgave Dyer for his misbehavior four years earlier when he decorated horse-drawn carts with hundreds of prostitutes and patronage workers and made them the centerpiece of his inauguration day parade.

Deafening Support

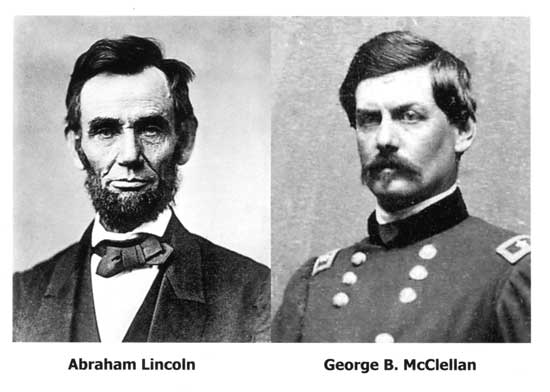

Joseph Medill, editor of the Chicago Tribune, devises a plan in 1860 to ensure that his candidate, Abraham Lincoln, wins the Republican nomination for president at the party’s upcoming convention in Chicago. Thousands of Lincoln “supporters” are brought to the city free of charge (by train) in an effort to stack the convention hall in favor of Lincoln. The supporters are told to report early to the convention hall, jam the doors, fill as many seats as possible and begin to shout in favor of their candidate. They are so effective that a newspaper reporter writes: “It was like all the hogs ever slaughtered in the Cincinnati stockyards giving their death squeals — all at the same time.”

Election Insurrection

Democrats in Chicago team up with Confederate sympathizers in an effort to derail Lincoln’s re-election in 1864. The plan is to release more than 8,000 Confederate prisoners of war that are held at Camp Douglas during the Chicago elections, have them stuff the ballot boxes in favor of the Democratic candidate, Gen. George McClellan, and then sack and loot the city, burning everything in their path that they could not carry. The “Chicago Conspiracy,” as it is called, is thwarted when informers tip the Camp Douglas commander in advance of the raid and the insurrectionists are arrested at their hotel.

Identifying Judas

During the Chicago elections in 1915, Oscar Depriest, a Black alderman, is reviewing the post-election votes in his all-Black ward. He sees 272 total votes cast — 271 of which are for his mayoral candidate, Republican “Big Bill” Thompson. “I know who double-crossed here!” Depriest exclaims in outrage. “Go out and find Mose Jackson and give him a raking over the coals.”

An Explosive Victory

To assure “Big Bill” Thompson’s re-election as mayor in 1927, Al Capone sends more than 1,000 goons and thugs into the city on the day of the primary. The goon squad breaks legs, arms, shoots Thompson’s political foes and throws hand grenades into polling places where Thompson was expected to do poorly. So many hand grenades are thrown that the event becomes known as the “Pineapple Primary.” Capone’s thugs repeat their activities on election day and Thompson is re-elected.

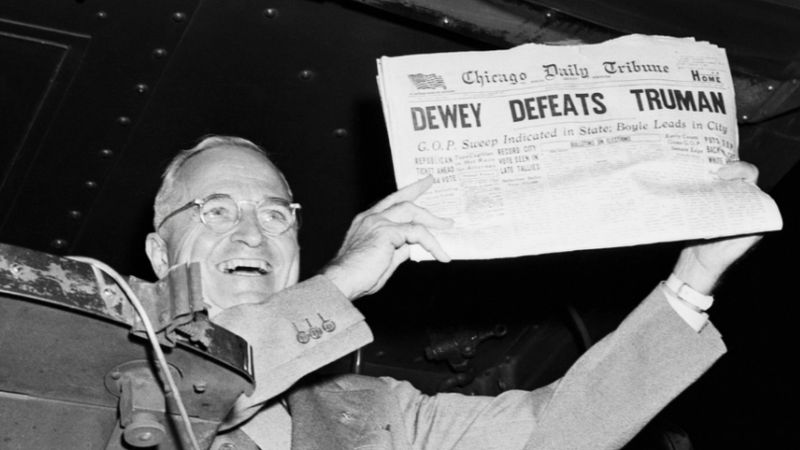

Beat the Press

Because of a printers’ strike, the Tribune’s 1948 Chicago elections edition goes to press hours earlier than usual, before the polls have even begun to report results. Based on a sampling of voters that has not failed the newspaper in its election coverage in more than 20 years, the Tribune projects the winner of the presidential election with the headline, “Dewey Defeats Truman.” The poll and the Tribune are wrong and the next morning, a grinning Harry Truman is photographed derisively waving the front page of the newspaper to a crowd of supporters.

Don’t Mess With the Machine

In 1955, Republican Mayoral Candidate Robert Merriam attempts to beat his opponents to the punch by mailing campaign literature to a purloined list of registered Democratic voters. But the Democrats intercept the literature and send it back to Merriam with “addressee unknown” and “deceased” stamp marks. In retaliation, the Democrats and their candidate, Richard J. Daley, play the religion card — they send thousands of unsigned letters highlighting Merriam’s recent divorce and the children he abandoned to Catholic neighborhoods throughout the city. After the election, a victorious Daley gets a new license plate for his car. It reads “708 220” — the number of votes he received in this, his first citywide election. He keeps the license plate on his car for the next two decades.

Quote for the Ages

Asked why the reform platform of Robert Merriam wasn’t enough to carry him past Machine politician Richard J. Daley in the mayoral race during the 1955 Chicago elections, 43rd Ward Alderman Mathias “Paddy” Bauler, a longtime city tavern owner, explained it simply: “Chicago ain’t ready for reform yet.”

Stealing Home

In 1960, Mayor Daley is credited with steering the presidential election in the direction of John F. Kennedy with dirty tricks that only a Machine magician could muster. Kennedy miraculously carried Chicago by more than 400,00 votes although he carried Illinois by only 8,000 votes. On election night, the president’s brother, Robert Kennedy, allegedly called Daley and asked, “How many votes do we have in Cook County?” Daley allegedly responded, “How many do you need?”

Simple Math

Asked why Democratic Nominee Hubert Humphrey didn’t carry Illinois in the 1968 presidential election, Mayor Daley replied, “He didn’t get enough votes.”

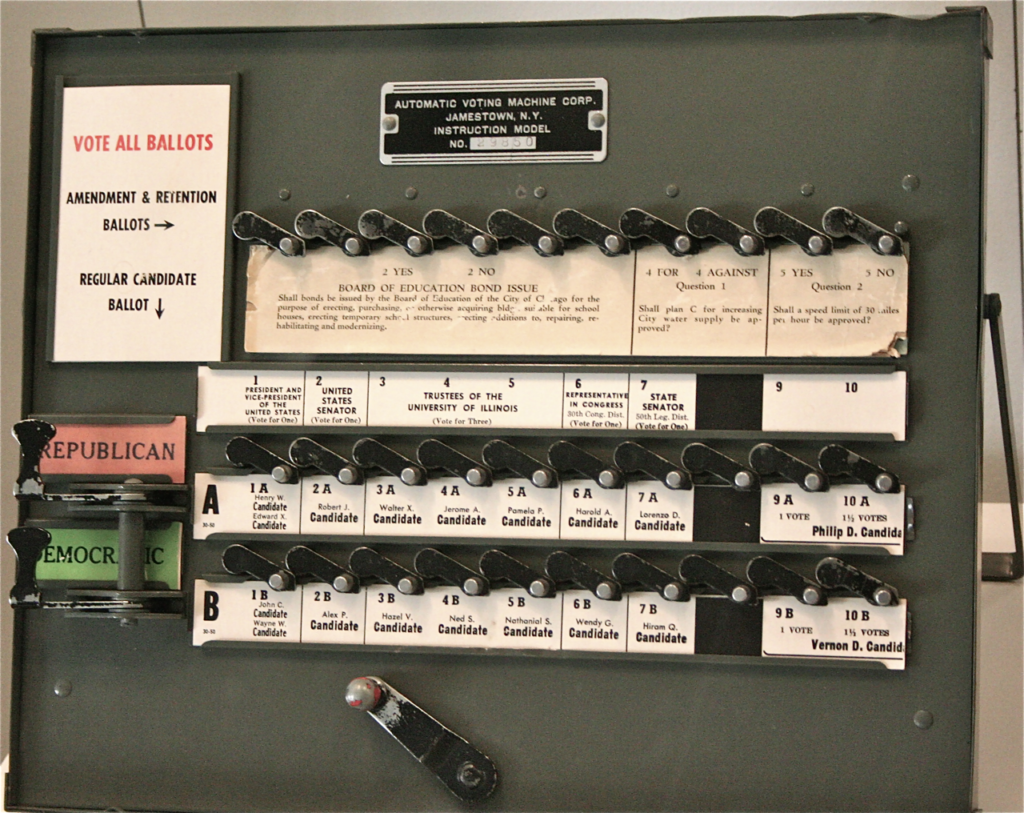

Actually Seeing a Few “Ghosts”

Two Democratic precinct workers and a Republican election judge are charged with 22 counts of “blatant” election fraud during the 1978 Illinois off-year elections. During the ’78 Chicago elections, a police patrolman reported that he heard bells ringing repeatedly at one voting machine in a North Side precinct. When he walked over to the machine, he saw one election official falsifying voters’ registrations and another using a voting machine to register multiple votes. The policeman asked what the men were doing. “We have six more to do,” one replied. “These are ghost voters.”

A Man of Conviction

In the 1987 mayoral election, political newcomer Sheneather Butler edges incumbent Alderman Wallace Davis, Jr. by the paper-thin margin of 100 votes. Incredibly, Davis has conducted his entire two-month campaign from a federal prison cell in the Metropolitan Correction Center where he was incarcerated and awaiting trial on federal bribery and extortion charges. He is believed to be the first alderman in the City Council’s 150-year history to seek re-election from a jail cell.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

According to the North American Vexillological Association, the world’s foremost organization dedicated to the study of the cultural, historical, political, and social significance of flags, there are five principles that lead to superior designs of a flag:

- Keep it simple

- Use meaningful symbolism

- Use two or three basic colors

- No lettering or organizational seals

- Be distinctive or be related to other flags

Chicago’s flag meets all of these criteria. In fact, a 2004 survey of the nation’s best city flags, conducted by the Vexillological Association, placed Chicago’s flag second in competition against hundreds of other municipal flags from cities across North America. (Washington D.C.’s municipal flag, which resembles George Washington’s coat of arms, finished first.) Not bad for a flag that was approved by the Chicago City Council more than 100 years ago and made its first public appearance a few days later (April 1917) at a car dealership in the Motor Row neighborhood on the city’s South Side.

Chicago’s official municipal flag is wildly popular. It is imprinted on virtually every city souvenir imaginable, is widely flown and displayed at buildings and residences across the city, imprinted on foods (cupcakes!) and, according to local artists, is one of the most popular designs at city tattoo parlors.

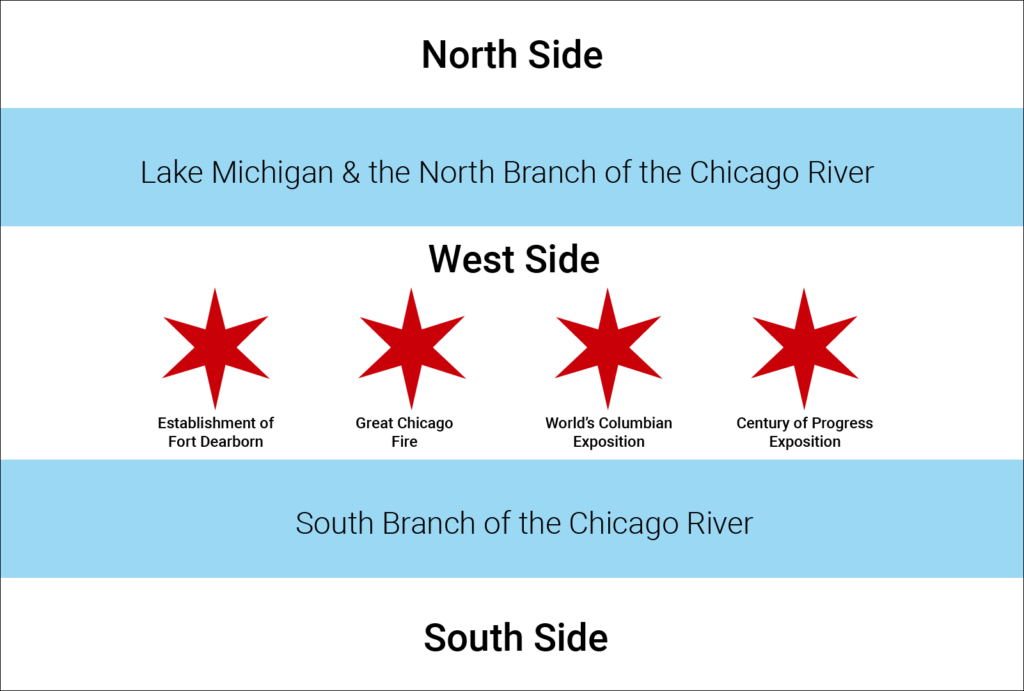

Who designed the flag? In 1915, Mayor William Hale Thompson established a municipal flag commission to review flag designs that would be entered in a contest. Poet, lecturer and author Wallace Rice was selected by the committee to develop rules that would govern the competition. Ultimately, the commission selected a design that was submitted by Rice himself. His design featured three main components — white stripes, blue stripes and six-pointed red stars — all of which symbolized key dates and facts about Chicago’s history and geographic location.

The three horizontal white stripes on the flag symbolize Chicago’s three regional sections — the top white stripe represents the North Side of Chicago, the middle white band the West Side and the lower stripe represents the South Side. Between the white stripes are two blue stripes which symbolize the water systems found within the area. The first blue stripe represents Lake Michigan and the North Branch of the Chicago River; the second blue stripe represents the South Branch of the Chicago River.

The last and perhaps most important design element of the flag are four six-pointed red stars that are centered within the widest horizontal white stripe (in the middle of the flag). The stars symbolize important dates in Chicago’s History — the establishment of Fort Dearborn at the mouth of the Chicago River (1803); the Great Chicago Fire (1871); the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893) and the Century of Progress Exposition (1933).

A commonly asked question about Chicago’s flag is why the stars have six points instead of the more popular five-pointed star. Asked why he selected six points instead of five, flag designer Rice said he hadn’t seen six points used on a flag before and thought their use would make Chicago’s flag unique.

The original flag designed by Rice in 1917 had only two red stars centered in the middle white stripe — one representing the Great Fire of 1871 and the one representing the 1893 Exposition. Rice said that he wanted to leave room for additional stars that might be added in the future. Years later, the city council approved adding the two additional stars to the flag’s design.

Will additional stars be added to Chicago’s flag in the years ahead? Stay tuned.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we’re currently running! L Stop Tours operates unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Its own city

For 106 years, the Chicago Union Stock Yards and adjacent meat packing plants were the most dominant businesses on Chicago’s South Side.

The Stock Yards complex was a veritable city unto itself — a 450-acre tract of land with 10,000 livestock pens with a capacity of tens of thousands of animals; hundreds of smoke-belching meat packing and rendering plants; a large post office dedicated primarily to Stock Yards workers; fully functional fire and police departments; an upscale hotel and world-renowned restaurant (the Stock Yard Inn); and a cavernous indoor stadium (the Chicago Amphitheatre), which hosted livestock shows, presidential nominating conventions and even the debut season of the Chicago Bulls (whose nickname was derived from the neighborhood’s most abundant commodity).

The Stock Yards District also was home to “Whiskey Row,” approximately 75 bars and taverns that were crammed into a one-mile stretch of South Ashland Ave.; more than 150 miles of railroad track that crisscrossed the neighborhood like steel mesh; and its own dedicated elevated transit line — the “Stock Yards Branch” — which featured stations that were named after meat industry names and businesses, such as Packers Ave., Exchange Ave., Swift and Armour.

While the Stock Yards withstood many challenges during its eleven-decade existence — several horrific fires, labor unrest, economic depressions, political pressure and ever-tightening food and safety regulations — the facility finally fell victim to a force it could not stop, the decentralization of the nation’s livestock and meat industries. Chicago’s meat packers simply closed shop and moved west to be closer to the supply of livestock. As a result, the Stock Yards no longer were needed as a marketing center. On July 31, 1971, the huge facility closed its famous front gate for the last time — it was the end of an era for one of Chicago’s largest and most important industries.

What’s there now?

Today, more than 50 years after its closing, there are very few remnants of the livestock or meat packing industries on Chicago’s South Side. The entire complex (livestock pens, packing plants, railroad shipping facilities) has been bulldozed — replaced by a massive development called “Stockyards Industrial Park,” an assortment of warehouses and manufacturing plants that are engaged in virtually every type of business other than meat packing. Nearby retailers no longer identify their shops with special neighborhood monikers (i.e. Stock Yards Hardware, the Yards Coffee Shop, etc.); and even that smell, that pungent, odoriferous, godawful smell that permeated every square inch of the South Side (and often the entire city), is gone.

Is anything left from Chicago’s glorious past as the livestock and meat packing capital of the world? Yes, but you have to know where to find it. That’s where we come in.

Welcome to L Stop Tours’ Self-Guided Tour of Chicago’s former Stock Yards and Meat Packing District.

Bubbly Creek

South Branch of the Chicago River near Ashland Ave. to W. 38th St.

This infamous one-mile stretch of waterway served as a dumping ground for waste materials from the city’s meat packers (blood, entrails, etc.) during the first 50 years of the Stocky Yards existence and was brought to everyone’s attention by Upton Sinclair in his novel, The Jungle. The Creek’s name is derived from small gas bubbles that regularly burst on the surface of the Creek — a byproduct of the, uh, byproducts in the water for all these years. Today, the waterway is much cleaner than it was in Sinclair’s day and the channel is suitable for boating or fishing. On a hot day, if you take a close look at the surface of the water from one of the area’s bridges, you can still see bubbles rising to the surface.

Live Stock National Bank

4150 S. Halsted

Built in 1925, this beautiful Colonial Revival-style building is a survivor. A replica of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, the bank outlasted the Great Depression, Chicago’s gangland wars of the Roaring ’20s and the horrific Stock Yards fire of 1934 (the bank opened for business the next day). The interior of the building was not what you would expect for a bank that mostly did business with blue collar meat plant workers, cattlemen and neighborhood residents — it was opulent, with chandeliers, plenty of marble, classical moldings, raised panels and fluted pilasters. The bank closed in 1965, six years before the Stock Yards would cease operation. Although many efforts have been initiated to redevelop the building over the years, none have made it the finish line. The building stands today on the northeast corner of Halsted and Exchange — empty and boarded up — waiting for someone to restore its former prominence.

Stock Yards Gate

Exchange Ave. at Peoria St.

Erected in 1875, this limestone gate, designed by renowned local architect John Welborn Root, stands today as one of the few visual reminders of Chicago’s past dominance in the livestock and meat packing industries. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1981, the gate marked the eastern entrance to the vast 475-acre Stock Yards, the largest facility of its kind in the world. Directly behind the gate is a memorial to Chicago Firefighters who died in the line of duty, especially those who perished in the Stock Yards Fire of 1934.

Stanley’s Tavern

4258 S. Ashland Ave.

The history of Chicago’s Stock Yards is interwoven with characters from the neighborhood who, like the Yards themselves, were long time survivors. Stanley’s Tavern is the last saloon still operating on Whiskey Row, the infamous stretch of Ashland Ave. between Pershing Rd. and W. 47th St, which housed dozens upon dozens of bars for thirsty Stock Yards employees, meat packing workers and neighborhood residents. Though Whiskey Row dates to the early days of the Stock Yards (1865), Stanley’s has an equally impressive history and has been serving loyal customers in the same location since 1935.

Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council

1823 W. 47th St.

Just southwest of the Stock Yards, Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood has long served as a beacon of light for immigrant workers seeking opportunity —jobs in livestock and meat packing industries and affordable nearby housing. Over the years the Back of the Yards neighborhood has been among the most ethnically diverse areas of the city — among the first arrivals were the Poles, Czechs and Lithuanians, then the Slovaks, African Americans and then Mexican Americans. Formed after the Great Depression, the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council is an organization whose mission is to “enhance the general welfare of all residents, organizations, businesses in our service areas.” It accomplishes this with social service and economic development programs that support the community. The Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council stands today as a reminder that neighborhoods and community organizations often outlive the businesses and industries that once were responsible for their birth and existence.

Swift Mansion

4500 S. Michigan Ave.

This ornate, Richardsonian Romanesque gray stone mansion was built in 1892 as a wedding gift to Helen Swift, the daughter of Gustavus F. Swift, the founder of Swift & Co. and also the inventor of the refrigerated rail car (for shipping meat carcasses long distances). Interestingly, Helen Swift married Edward Morris, the son of another large Chicago meat packer, Nelson Morris. The Morrises lived in the home until 1916 when they moved to another they built on nearby Drexel Ave. After serving as a residence for other families, the mansion was a funeral home and most recently was occupied by the Urban League and the Inner City Youth and Adult Foundation.

Stockyards Industrial Park

located in an area bounded by Pershing Road, Halsted Ave., W. 47th St. and Ashland Ave.

There is life after the Stock Yards, particularly in terms of the Stockyards Industrial Park, a collection of about 100 businesses (warehouses, manufacturing plants, offices) that have been built on the former Stock Yards property in the 50 years since the huge livestock facility closed. The Industrial Park is clearly marked — huge metal, gate-like structures with “Stockyards Industrial Council” inscribed on circular medallions arch over neighborhood streets, marking the boundaries and major arterials running through the park. Without these signs, it is virtually impossible to detect that the Stock Yards once stood here.

Railroad Tracks

3950 S. Morgan

The railroads played a leading role in the success of the Union Stock Yards over the years. Livestock-hauling freight trains brought hundreds of millions of animals Chicago annually from all parts of the country and refrigerated railroad cars (invented by meat packer Gustavus Swift in 1875) enabled meat carcasses to be shipped as fresh product back to those very same parts of the country that the livestock came from, and farther. Railroads were the transportation vehicle of choice until the 1950s when trucks made the process more efficient and economical. Though many of the railroad tracks that snake through the district are abandoned, some, including this set of tracks on Morgan St. are still active and in use.

Kent House

2944 South Michigan Ave.

Designed in 1883 by the prominent architectural firm of Burnham and Root, this lovely Queen Anne mansion was built for Sydney A. Kent, one of the founders of the Chicago Union Stock Yards and survives as one of the few remaining mansions on this former upscale stretch of South Michigan Ave. Recently converted into several condominium apartments, the building was designated a Chicago landmark in 1987.

Stock Yards L Branch

State Street and West 40th Street

In 1908, the South Side Elevated Railroad took over a little-used 2.8-mile railroad line running west from the Indiana Avenue Station (today’s Green Line) and extended it to the Stock Yards where it went around a big loop and headed back toward Indiana. The Stock Yard Branch, as it was called, was popular with the 50,000 area workers as well as tourists who would take the L from downtown to visit the huge Stock Yards complex. The Chicago Transit Authority, which assumed control of Chicago’s public transit system in 1947, discontinued operations on the line in 1957 due to declining ridership. This remnant of the elevated line (a “severed” overpass on State Street near West 40th Street) reveals where the former elevated line used to run.

Vienna Beef

1000 W. Pershing Road

One of Chicago’s most prolific and popular meat companies, Vienna Beef, which got its start when its founders sold hot dogs at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, never had a manufacturing facility located anywhere near the Stock Yards or Packingtown…until 2013. That’s when the Chicago-based company moved its manufacturing facility from its long-time North Side location to its present site on the northern edge of what is now Stockyards Industrial Park. While other meat packing plants and food manufacturing facilities have long-since vacated the South Side and Stock Yards District, Vienna Beef stands today as one of the few actual meat companies that still operate within the former Stock Yards district — even though it is a relative newcomer to the neighborhood.

Packers Avenue

1300 west for 6 blocks from 4000 south to 4600 south

Today, Packers Avenue is just another street sign that labels a non-descript roadway in an industrial park. Over 100 years ago, the largest meatpackers in the world lined this street, which got its name from the businesses that operated here. Another area street, Exchange Avenue (runs west at 4150 S. Halsted), is named after the Exchange Building of the Union Stock Yards, an office building where the paperwork for all live animal transactions was completed.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the history of controversial monuments in Chicago, visit our blog to learn more insightful facts and history about Chicago.

“In fourteen hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue, because the truth has now emerged, his Chicago statues have been purged.”

Updated version of the “Columbus Day” poem

Christopher Columbus Statues

When I was a youngster in elementary school, I was taught that Christopher Columbus was a pretty important historical figure. Not only did he discover the New World (the Americas), he did so on an expedition that included three tiny ships: the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria. On Columbus Day, our teachers had us recite a corny poem that commemorated the explorer’s accomplishments.

Today, however, it’s a completely different story. It seems that everything I was taught about Columbus was nothing more than propaganda, positive spin. Apparently, the true line on Columbus is that he was a murderer, an enslaver of indigenous people and, with the help of his crew and fellow travelers, the carrier of new diseases to the Americas. In other words, Columbus is not exactly someone we should be honoring with a national holiday or with one of our monuments in Chicago. He’s far too controversial a figure for today.

Somewhat reluctantly, Mayor Lori Lightfoot agreed with this sentiment and on July 25, 2020, under the cover of darkness, quietly ordered two monuments in Chicago that were statues of Christopher Columbus removed from their pedestals — one at the southern tip of Grant Park and the other at Arrigo Park (in the heart of the Little Italy neighborhood). According to Lightfoot, the statues were removed in order to protect public safety which had been threatened the week before when an angry mob of protesters tried to tear the statues down themselves. A number of protesters and policemen were injured in the disturbance.

This is not the first incidence of controversial monuments in Chicago causing angst and violence in the city, however.

Stephen A. Douglas Tomb

On the angst side of the equation is a 96-foot memorial statue at 636 E. 35th St. that rises over the tomb of Stephen A. Douglas, U.S. Senator from Illinois, who is best known for his debates with Abraham Lincoln over the issue of slavery and who lost to Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election. Once a popular figure throughout Illinois, Douglas’s name and reputation have taken a beating in recent times — his wife’s family were slaveholders in Mississippi and Douglas himself was politically soft on the issue, leaving it up to states to decide for themselves to legalize or abolish it. Today, he is perceived as being on the wrong side of the slavery issue. And as if to add gas to a long-smoldering fire, his statue overlooks the vibrant and diverse Bronzeville neighborhood, the center of African American life and culture in Chicago. Perhaps Mr. Douglas is not the most suitable historical figure for the residents of Bronzeville to look up to (literally and figuratively).

Haymarket Statues

One of the monuments in Chicago that caused violence was a statue erected in 1889 in Chicago’s Haymarket District (near West Side) that commemorated the Haymarket Square Riot of 1886, in which protesters fighting for workers’ rights became involved in a melee that killed seven policemen, four civilians and injured dozens. The ensuing riot was — and continues to be — one of the most significant and important events in the history of the global labor movement.

The statue erected three years after the incident turned out to be one of the most controversial statues in Chicago’s history. It was a nine-foot depiction of a Chicago police officer with his arm raised. That was it. Nothing about the fight for workers’ rights and no mention of the others killed and injured that day. Needless to say, many people were displeased with the one-sided nature of this commemoration — glorify the police and ignore the noble cause of the demonstrators. As a result, the statue became a “target” for individuals, groups and organizations.

The statue erected three years after the incident turned out to be one of the most controversial statues in Chicago’s history. It was a nine-foot depiction of a Chicago police officer with his arm raised. That was it. Nothing about the fight for workers’ rights and no mention of the others killed and injured that day. Needless to say, many people were displeased with the one-sided nature of this commemoration — glorify the police and ignore the noble cause of the demonstrators. As a result, the statue became a “target” for individuals, groups and organizations.

Unlike other monuments in Chicago, the Haymarket statue has a long history of being destroyed and built back up.

On May 4, 1927, a streetcar motorman deliberately sidetracked his vehicle and crashed it into the monument saying he was “sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised.” After several additional vandalizations, the statue was relocated to nearby Union Park for better public visibility. When nearby expressway construction caused the statue to be moved back to its original location in the 1950s, it once again became the target of vandals. In 1968, demonstrators protesting the Vietnam War covered the statue with black paint; in 1969, radicals from the Weather Underground blew the statue to bits by placing a bomb between the policeman’s legs; in 1970, the Weather Underground blew up a “rebuilt” Haymarket statue in the same location. Rebuilt yet again a year later, Mayor Richard J. Daley installed a 24-hour guard next to the statue which cost the city $67,000 per year. In 1972, the city finally got smart — the statue was relocated to a courtyard inside Chicago Police Headquarters on west 35th St. where it stands today.

However, a beautiful thing has happened at the original site of the Haymarket Memorial — and it serves as a guide for those who wish to commemorate historic figures and events throughout our city…today and in the future.

In 1992, the City of Chicago erected a new memorial statue (151 N. Des Plaines St.) to honor and draw attention to all of the people and the events of day. A plaque underneath a bronze statue of a speaker’s wagon reads:

A decade of strife between labor and industry culminated here in a confrontation that resulted in the tragic death of both workers and policemen. On May 4, 1886, spectators at a labor rally had gathered around the mouth of Crane’s Alley. A contingent of police approaching on Des Plaines Street were met by a bomb thrown from just south of the alley. The resultant trial of eight activists gained worldwide attention for the labor movement and initiated the tradition of ‘May Day’ labor rallies in many cities.

The lesson?

History, like art, is best understood — and becomes richer — when it is viewed from different perspectives and it educates in a clear and unbiased fashion. It is also important to remember that attitudes and values of people change over time — what may have been acceptable years ago may no longer be tolerable today.

Last week, Mayor Lightfoot unveiled a new committee that will review all of the monuments in Chicago and statues to determine which pieces “warrant attention or action,” will recommend new monuments or public art (with a nod toward underrepresented women, minorities or historical figures) and engage Chicagoans by creating a dialog about the city’s past.

It’s a monumental step in the right direction.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

If you enjoy reading about the most frequently asked questions about the L and want to learn more about the city and its history, then consider signing up for our blog newsletter!

Does anyone remember Riverview Park in Chicago?

Unless you’re over 60, have grandparents who like to reminisce, or are an avid student of local history, my guess is that you’ve never heard of the place. And that’s understandable. Riverview Park, an amusement park that was located at Belmont and Western Avenues on the North Side, closed in 1967, ending its 65-year run as one of the most popular leisure-time attractions in Chicago and also in the United States. While it was open for business, more than 200 million visitors passed through its castle-like front gate.

Although it began life in 1902 as a skeet shooting range for local residents, Riverview Park in Chicago quickly pivoted to amusements (rides and other attractions) in order to appeal to a wider range of customers. The strategy worked and within a few years, the park began to grow steadily, with new rides and attractions added annually. In the 1950s, Riverview Park in Chicago billed itself as the largest amusement park in the United States with 40 major rides and attractions and a staff of more than 1,000.

By the mid-1960s, however, it was a completely different story. Declining attendance and escalating real estate taxes were to Riverview what kryptonite was to Superman — fatal. In 1967 the 70-acre park shut down and was quickly sold to a LaSalle Street investment firm, which, in turn, sold it to a paper manufacturer for $6 million. Today, a shopping center, the DeVry Institute of Technology and the Chicago Area 6 Police headquarters occupy the amusement park’s former space.

What became of Riverview’s famous rides and attractions?

Unfortunately, most were smashed into oblivion shortly after Riverview Park in Chicago closed its doors for the final time. Although the park’s owners held an auction just after closing, none of the 50 bidders wanted such attractions as the Pair-O-Chute Jump, the Space Ride, the flash High Ride or even the world-famous Bobs roller coaster.

In its day, the Bobs was billed as the world’s faster roller coaster, attaining a top speed of more than 60 miles per hour. According to a 1953 article in the Chicago American, the Bobs was the most thrilling ride in America.

Not long ago, the Chicago Sun-Times recalled the Bobs in a feature article: “It was a mind-numbing, body-bruising, 120-second dash through twisted metal and rickety white wood; when it was over, you’d be battered and breathless.”

Nonetheless, it was unwanted at the auction, and shortly thereafter it was demolished and sold for scrap, along with Riverview’s five other roller coasters — the Fireball, the Wild Mouse, the Silver Streak, the Comet and the Greyhound. Chute the Chutes was also demolished, as was the giant genie’s head that grimaced above the entrance to Aladdin’s Castle.

What, if anything, was saved from Riverview?

Many of the smaller rides, like the Ferris wheel and miniature train, were sold to carnivals in different parts of the country. And a Chicagoan bought four children’s rides — The Whip, Kiddy Merry Go-Round, Kiddy Bug and Kiddy Boat — for $2,800.

Believe it or not, one famous ride from the storied amusement park is still in operation today, although you must travel to Georgia to ride it. Head to Atlanta’s Six Flags Over Georgia Amusement Center and you will see, in all its glory, the famous Riverview carousel, one of the three original rides at the Chicago amusement park.

In 1907, Riverview founders William and George Schmidt commissioned Swiss and Italian immigrant wood carvers to whittle 72 customized horses and four chariots for a merry-go-round that was to take center stage at Riverview Park in Chicago. They did, and the 96-passenger carousel, and hand-carved masterpiece, was the result.

In its Georgia location, the carousel looks much as it did at Riverview Park in Chicago when it opened in 1908. A wedding cake-shaped shelter — identical to the one that protected it at Belmont and Western — was constructed to protect the storied ride from the elements. Now in its 107th year of operation (59 years in Chicago, 48 in Atlanta), the Riverview Carousel has become a nostalgic fan favorite at the Georgia park and continues to rank as one of its most popular and treasured rides.

Laugh Your Troubles Away

For about half of its six-decade run in Chicago, Riverview was indeed the world’s largest amusement park, surpassing, for example, the four-park setup at Coney Island in New York and also local rivals, such as White City and Joyland on Chicago’s South Side.

For many years, the marketing slogan at Riverview Park in Chicago was “Laugh Your Troubles Away.” In these pandemic times, when life plods along at a snail’s pace, when entertainment options are extremely limited and our lives have literally been turned upside down, a place to laugh our troubles away sounds like a pretty good place to be.

For those of us who remember Riverview Park in Chicago, the memories of a truly great amusement park will have to get us through, instead.

To see more of Riverview Park, check out Images of America: Riverview Amusement Park.

To learn more about the history, check out Laugh Your Troubles Away: The Complete History of Riverview Park

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

To learn more about the history of Chicago and its famous establishments, book a neighborhood tour with L Stop Tours today!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

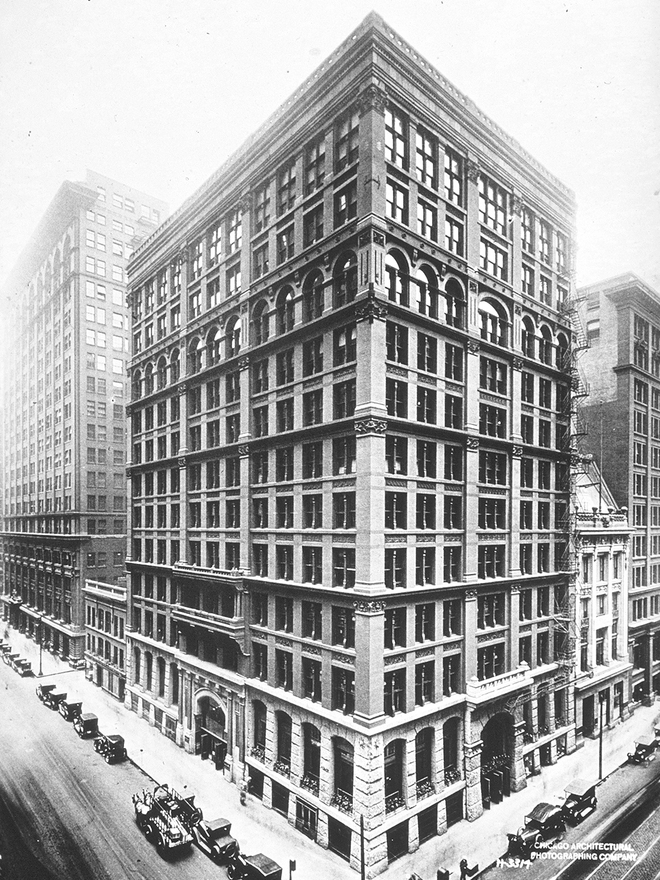

To learn the history of famous Chicago skyscrapers, you need to go back more than 100 years. Shortly after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, the City of Chicago passed new laws that outlawed the use of wood in new building construction. This preventative measure paved the way for heat resistant materials such as brick, limestone, marble, and Terracotta tile, all of which found new popularity among local architects and building designers.

These fireproof materials lead to a boom in new construction projects, especially high-density buildings in the Loop that housed a variety of tenants. These multi-story buildings featured massively thick load-bearing walls, walls that supported the weight of the entire building above it. Because brick or stone can only support so much weight, buildings built with load-bearing walls often topped out at around 10-12 stories.

In 1884, at the height of this building boom, architect and engineer William LeBaron Jenney was commissioned by the Home Insurance Company of New York to design its regional headquarters in Chicago at the corner of Adams and LaSalle Streets. Stepping out of the load-bearing wall architectural box, Jenney supported the building with a fireproof steel frame that resembled a skeleton around the entire construction. Because the frame dispersed the weight of the building, it was much lighter than its load-bearing cousins and, thus, was able to be built taller. This innovation, experts acclaimed, made the Home Insurance Building the world’s first modern skyscraper and Chicago home to the world’s first skyscraper.

Since then, the city has become world-renowned for its architectural achievements and, of course, its vast array of famous Chicago skyscrapers.

We’ve put together a list of our favorite famous Chicago skyscrapers:

- Fisher Building

- Marquette Building

- Monadnock Building

- Old Colony Building

- Rookery Building

- Lake Point Tower

- Chicago Hilton

- Merchandise Mart

- Old Chicago Main Post Office

- Willis Tower

- Aon Center

- 875 N. Michigan Ave.

- Marina City

- Tribune Tower

- Wrigley Building

We’ve divided our list of famous Chicago skyscrapers into three groups —Pioneers, Record Breakers and Icons.

Pioneers

Fisher Building

Completed in 1896 by D.H. Burnham and Company, the Fisher Building survives today as the oldest building in Chicago that is more than 18 stories high (it has 20 floors). Its neo-Gothic design, notable for the many carvings and sculptures that decorate its terra cotta facade, was worthy of national recognition — it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Built near the Loop’s Financial District, the building is one of the few in the area that is devoted entirely to residential apartments.

Marquette Building

Built in 1895, the Marquette Building is an early steel-frame skyscraper with masonry cladding. The building is named after explorer Father Jacques Marquette who, in 1674, was the first European settler in Chicago. What makes Marquette one of the most famous Chicago Skyscrapers is its ornate, two-story lobby which features four intricate Tiffany mosaics that depict events in Marquette’s life, including his exploration of Illinois, Native Americans he met along the way and a scene that depicts his burial. Designed by the architectural firm of Holabird & Roche, the building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1973.

Monadnock Building

Named after a mountain in New Hampshire, the Monadnock Building was built as two separate buildings that were later joined into a single building. When it was completed in 1891, the north half of the building was, at 16 stories, the tallest load-bearing brick building in the world —the walls at its base are 6 feet thick. When the south half of the building was completed in 1893, the Monadnock Building became the largest office building in the world, featuring more than 1,200 offices and occupancy of over 6,000 workers. Known for its decorative aluminum spiral staircases and bay windows, the Monadnock Building is both a famous Chicago skyscraper and National Landmark.

Old Colony Building

Built in 1893, the Old Colony Building, named in honor of the original Plymouth Colony founded by the Pilgrims, is a 17-story structure with beautiful curved bay windows on each of the four corners of the building. Originally built as an office building, the Old Colony was converted to an apartment building in 2015 and today mainly serves as housing for college students attending school in the South Loop neighborhood. It was placed on the National Register for Historic Places in 1976.

Rookery Building

One of the most historically significant buildings and most famous Chicago skyscrapers, the Rookery was designed by the architecture firm of Burnham & Root and features a combination of load-bearing walls and an interior steel frame. It was completed in 1888. The centerpiece of the building is a stunning two-story lobby, redesigned in 1905 by Frank Lloyd Wright, with a skylight and a mesmerizing oriel staircase that visibly climbs to the 12th floor from the second. Named a National Historic Landmark in 1975, the Rookery Building also has been used in several motion pictures including “Home Alone 2” and the “Untouchables.”

Record Breakers

Lake Point Tower

This sleek, graceful, 70-story Mies van der Rohe-influenced structure was completed in 1968 and was the tallest apartment building in the world when it opened. Located adjacent to Navy Pier, Lake Point Tower is the only skyscraper in Chicago that sits on the east side of Lake Shore Drive and, given the city’s reluctance to approve any shoreline construction for environmental reasons, it is likely to stay that way for the foreseeable future. According to the developers, the shamrock shape of the building ensures that every unit in the building has a view of Lake Michigan.

Chicago Hilton

When it opened in 1927, the Chicago Hilton (formerly the Stevens Hotel) offered 3,000 rooms for guests and was, unequivocally, the largest hotel in the world. The property offered a wide variety of services and features for guests, including a miniature golf course, a concert music library, a 1,200-seat theater, a 7-chair barbershop and a small hospital with an operating room. In the past couple of decades, the hotel has been used as a backdrop for several Hollywood movies, including “The Fugitive,” “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” “U.S. Marshalls” and “Road to Perdition.”

Merchandise Mart

Built by retailer Marshall Field so he could consolidate his warehouses into a single facility, the Merchandise Mart was the largest building in the world (4.2 million square feet) when it opened in 1930 on the north bank of the Chicago River. Spanning two city blocks, the Merchandise Mart is renowned worldwide for the vast number of furniture, fabric and decorator designers that operate showrooms throughout the building. In the last several years, the building also has come to be known for “Art on the Mart,” the largest digital art projection program in the world.

Old Chicago Main Post Office

Spanning 60 acres (2.5 million square feet), the 12-story Old Chicago Main Post Office — the one that straddles the Eisenhower Expressway with a huge hole for cars to drive through — was the largest post office in the world when it was expanded in 1932 to accommodate Chicago’s booming mail needs (primarily catalogs that were distributed by Montgomery Ward, Spiegel and Sears). When the city built a new, more efficient facility in 1997, the Old Main Post Office sat idle and unused for more than 20 years. Today, it has been redeveloped and is now home to such companies as Walgreens, Uber, Ferrara Candy and PepsiCo.

Willis Tower

When the 110-story Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) was completed in 1973, it became the tallest building in the world, a title it would hold for 25 years. Today, one of the most famous Chicago skyscrapers is the third tallest building in the United States and 23rd tallest building in the world. Although Sears vacated the tower in 1995, it retained the naming rights until it sold the building in 2003. When London-based insurance broker Willis Group Holdings leased more than 140,000 square feet of office space from the new owners, they obtained the naming rights and on July 16, 2009 renamed the tower.

Icons

Aon Center

The 83-story Aon Center is the fourth tallest building in Chicago, standing in line behind Willis Tower, Trump Tower and the all-new Vista Tower. A sleek, minimalist tower clad entirely in white granite, the Aon Center takes its name from the Aon Corporation (insurance) which became the building’s primary tenant in September 2001. Completed in 1973, the building was built by the Standard Oil Company of Indiana and for many years was affectionately known as “Big Stan.”

875 N. Michigan Ave.

Formerly known as the John Hancock Center), 875 N. Michigan Ave. is one of the best known — and most photographed — famous Chicago skyscrapers. A gradual taper of the building’s frame from its base to the top floor along with its distinctive X-bracing on the exterior walls of the building make it easy to identify when viewing the city’s skyline from a distance. When the building topped out on May 6, 1968, it was the second tallest building in the world; today it is the fifth tallest building in Chicago.

Marina City

In 1963, when the two towers of Marina City opened on the north bank of the Chicago River, Chicagoans thought that architect Bertrand Goldgerg’s futuristic skyscrapers were something right out of the “Jetsons.” The complex was designed to be a “city within a city” — it included a movie theater, gym, swimming pool, ice rink, bowling alley, stores, restaurants, a small adjacent office building and a marina. With 450 apartments in each tower, Marina City was the first post-war high-rise complex built in the United States and it is widely credited with beginning the residential renaissance of inner city America.

Tribune Tower

In 1922, the Chicago Tribune hosted an international design competition for its new headquarters to mark the newspaper’s 75th anniversary. The newspaper challenged architects worldwide to design “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world.” The winning entry was a neo-Gothic design by New York architects John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood that featured flying buttresses near the top. Construction on the Tribune Tower was completed in 1925 when the building topped out at 463 feet. The Tribune sold the building in 2018 to developers who plan to convert it into condominiums,

Wrigley Building

Built by the William Wrigley Jr. Company (chewing gum) from 1921-24, the Wrigley Building was the first Chicago skyscraper to be constructed north of the Chicago River (made possible by the 1920 construction of the DuSable Bridge that spanned the river at its doorstep). The building is actually two separate towers — the 30-story South Tower and the 21-story North Tower — that are connected with walkways at ground level and the third and fourteenth floors. Clad with more than 250,000 pieces of terra cotta, the Wrigley Building looks stunning when the building is bathed in floodlights at night. The spire and clocktower of the Wrigley Building take their inspiration from the Giralda tower of Seville Cathedral in Spain.

Most of these skyscrapers and more beautiful buildings and structures can be seen on a variety of our Chicago city tours. If you’d like to learn more about what tour is right for you, please contact us!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Singin’ the Blues of the City at Chess Records in Chicago

Several decades ago, in a small terra cotta structure located at 2120 S. Michigan Ave., a recording studio helped propel a Chicago record label into one of the most famous in the music business. But what happened to Chess Records in Chicago, the city’s most prolific record company in the 20th century?

In 1968, Leonard and Phil Chess, founders of the firm, sold it to a company called GRT, which promptly turned around and sold it to Sugar Hill Records in the mid-1970s. MCA Records, part of the entertainment conglomerate that counts among its holdings Universal Pictures, now owns the 10,000 hours of Chess recordings and is presently reissuing the Chess artists to newer, younger audiences.

More than anywhere else in the world, Chess Records in Chicago was famous for popularizing the blues and helping introduce it to the mass market — both domestically and overseas. And this introduction, according to many in the music industry, literally changed the course of music history.

Listen to The Best of Chess Records on Amazon Music as you read! As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

The Story of Chess Records in Chicago

It began in 1946 when the Chess brothers were operating a dingy bar at 3905 S. Cottage Grove called the Macamba, which was a dark, smoky lounge where musicians often hung out. Lionel Hampton, Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker and Ella Fitzgerald sat in the house band.

Leonard Chess, acting on a hunch, left the club to establish his own record company, recording people who played at the Macamba. Leonard’s first artist, on a label he called Aristocrat, was Andre Tibbs, who sang the “Union Man Blues.”

Before the end of the decade, the Chess label was established and the firm had moved into its two-story headquarters on South Michigan Ave., about 20 blocks south of the Loop.

The sound the Chess brothers were after was a kind of electrified-Southern, or Mississippi Delta blues. It was a distinctive sound, featuring a hard-driving beat that, depending on the artist, might include a little gospel, some jazz or what later would become known as “soul.” And the brothers searched throughout the South to find exactly the right type of artists to record.

The Success

Among the legendary musicians who climbed the long flight of stairs to Chess’ second floor recording studios on Michigan Avenue were Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Sonny Boy Williamson, Ramsey Lewis, Etta James, Frontella Bass, Willie Dixon, the Rev. C.L. Franklin and his daughter Aretha and Chicago’s legendary Muddy Waters.

By the late 1950s, business at Chess Records in Chicago was booming and the company began to add other labels, including Argo, Checker, Cadet and Cadet Concept. Chess was becoming known as the international headquarters for the blues.

The Impact

And the sounds coming out of the Michigan Avenue studios were extremely influential, particularly in Britain. In Liverpool, rhythm and blues records were in great demand among local youth and particularly among two young rock band members named Lennon and McCartney.

In London, another rock-star-to-be, Keith Richards, met a young musician by the name of Mick Jagger in a record shop because he noticed Jagger had a Chess records album under his arm. Later, when Richards and Jagger put together a rhythm and blues-based rock band, they called themselves the Rolling Stones after a Chess-recorded Muddy Waters cut called “Rolling Stone.”

A few years later, when the Rolling Stones were on their first tour of America, they stopped in to record tracks for the “12 x 5” album at Chess Records in Chicago. One of the cuts earned the title “2120 S. Michigan Ave.,” a kind of dedication to the place that produced the music that influenced them the most.

“I recorded some of my biggest hits at that address,” said rock pioneer Chuck Berry in the Chicago Sun-Times. “I have a lot of memories of it. They were great days of great music.”

The Legacy

Although Chess Records in Chicago vanished from the local scene when the company was purchased by GRT in 1968, the building where it all took place on south Michigan Avenue still stands today. It achieved landmark status from the City of Chicago in 1990.

Today the building is owned by the estate of legendary blues artist Willie “Wang Dang Doodle” Dixon and it has become a museum. The organization that operates it is called the Blues Heaven Foundation, which raises funds for music scholarships, helps supplement the income of blues musicians and helps promote the blues legacy.

Chess Records, 2120 S. Michigan Ave. can be seen on our “Prairie District: Street of the Elite” tour.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

When it gets dark on April Fools Day, you can see them gathering at various points along the lakefront.

They’re well-prepared for a long evening — Coleman lanterns, barbecue grills, charcoal, portable televisions, lawn chairs and ice chests full of beer. Rain gear is vogue if the sky shows even the slightest hint of foul weather; playing cards and poker chips are on hand in case there isn’t much action during the evening.

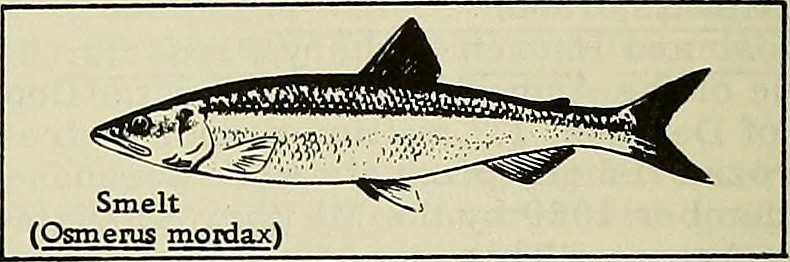

These are Chicago’s hardy smelt fishermen, a group of enthusiastic anglers who brave frigid weather, ungodly fishing hours and boredom in order to capture a much-prized seasonal favorite — the elusive smelt — a short, 4-6 inch fish that spawns along the shoreline of Lake Michigan for six weeks every spring.

The Chicago File, April 1991

When I wrote the above article 29 years ago in The Chicago File, fishing for smelt along Chicago’s lakefront during the month of April was an extremely popular activity. It was highly promoted by the Chicago Park District as a unique seasonal outdoor activity and, as a result, fishermen from all over the Midwest came to Chicago to spend an evening or two on the lakefront capturing the much sought-after fish.

Why was smelt fishing so popular?

Much of the appeal of smelt fishing stemmed from the fact that it was a highly unique fishing experience, it was radically different than other forms of the sport. Smelt fishing, for example, had always been a nighttime activity — in Chicago it was (and still is) permitted only during the month of April between the hours of 7 p.m. and 1 a.m. In other words, it’s the perfect sport for night owls and insomniacs.

Smelt fishing required special equipment in order to be successful. To catch smelt you used seine, dip or gill nets of a certain size – they could not exceed 12 feet in length or six feet in depth. The mesh size of the net could be no larger than one and a half inches. The netting restrictions were crafted and enforced by the Chicago Park District and were designed to ensure that no fishermen took more than their fair share of smelt from the water during any given net hoist.

Another aspect of smelt fishing that made the sport unique was the somewhat odd local tradition in which fishermen felt it necessary to prepare, cook and consume the fish within minutes of it being caught. This is where the grill, charcoal, ice chests of beer and cooking oil they dragged to the beach came in. All of these items were necessary in order to have a proper “smelt fry” on an otherwise deserted Chicago beach in the middle of the night.

So, yes, for more than a century, the unique sport of smelt fishing has been a popular Chicago outdoor sports activity. And to this day, there are plenty of smelt fishermen who eagerly await the arrival of April 1 so they can head out to the lakefront and net themselves some smelt. The only problem is that now, Chicago has more smelt fishermen than there are likely smelt in Lake Michigan.

What happened to the smelt?

Ecologists point to several changes in Lake Michigan that have caused the smelt population to dwindle over the years. Coho Salmon, for example, have now become predators of smelt because other fish they used to consume (like lake herring) have vanished completely from the lake. Another reason there are so few smelt in the lake is because of the rapidly multiplying population of invasive zebra mussels in the lake. Because zebra mussels are relatively new to Lake Michigan and because they compete with fish for lake plankton (food), there is less food available for consumption. As a result, the smelt get less plankton and many do not survive.

Ecologists point to several changes in Lake Michigan that have caused the smelt population to dwindle over the years. Coho Salmon, for example, have now become predators of smelt because other fish they used to consume (like lake herring) have vanished completely from the lake. Another reason there are so few smelt in the lake is because of the rapidly multiplying population of invasive zebra mussels in the lake. Because zebra mussels are relatively new to Lake Michigan and because they compete with fish for lake plankton (food), there is less food available for consumption. As a result, the smelt get less plankton and many do not survive.

The decline of smelt in Lake Michigan has also caused many smelt fishing festivals and lakeside cookouts to be canceled, as well. North suburban Lake Forest recently canceled Smelt-O-Rama, a long-standing event on the lakefront that taught youngsters how to catch, clean and cook the tasty little delicacies. Similarly, the Park District of Highland Park canceled its long-running Smelt Fest because there simply weren’t enough fish being caught to make it viable.

According to the Chicago Park District, smelt season will again open on April 1 and will run through the end of the month — with the same fishing hours, the same net restrictions and the same rules about netting too many fish, although this really hasn’t been an issue for the several years.

So, what do you do if you crave smelt and want to down a few this evening?

The best advice? Let someone else find it and net it.

One of my favorite seafood joints on the South Side, Calumet Fisheries, still has smelt on their a la carte menu in half- and full-order portions. I suspect, however, that the fish come from Lake Erie or somewhere else where they are in greater supply.

Sound fishy?

Enjoy.

If you want to learn more about Chicago’s history, and the events and people that made the city what it is today, consider going on a Chicago tour with L Stop Tours. Book a unique neighborhood tour today!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Looking for something interesting to do on a dreary afternoon?

Take the CTA Red Line to the Sheridan stop and walk a few blocks west to the Clark St. entrance of Graceland Cemetery — one of the most historic sites in the City of Chicago.

Graceland Cemetery is the final resting spot for some of Chicago’s best known citizens and also serves as home to some of the most spectacular grave sites and monuments in the entire city. Getty Tomb, designed by well-known architect Louis Sullivan (who is also buried at Graceland), is an official Chicago landmark and is perhaps one of the most photographed tombs in the United States. It is the final resting spot for Carrie Eliza Getty, wife of wealthy Chicago lumber baron Henry Harrison Getty.

Graceland Cemetery

Two important and often photographed sculptures by Lorado Taft are also found at Graceland — Eternal Silence (or the Statue of Death) and The Crusader. Additionally, a granite baseball two-feet in diameter, with stitching, marks the grave of William Hulbert, founder of Major League Baseball’s National League.

One of Chicago’s most famous businessmen, hotelier Potter Palmer, is buried at Graceland with his wife, Bertha, underneath a majestic columned monument. Nothing less would have been fitting for the Palmers. Mr. Palmer was the founder of one of the grandest hotels in the city, the Palmer House; Mrs. Potter Palmer was a revered socialite who devoted herself to many philanthropic causes throughout her life.

Not far away is the majestic monument and tomb of George Pullman, best known for his Pullman Palace railroad cars and the unique, self-contained industrial town he established on the city’s South Side.

The list of famous names goes on. Also buried here are newspapermen Joseph Medill (editor of the Chicago Tribune) and Victor Lawson (founder of the Chicago Daily News); meatpacker and industrialist Philip Armour; inventor of the reaper Cyrus McCormick; retailer Marshall Field; Chicago’s first detective and founder of the Secret Service, Allan Pinkerton; one of Chicago’s first settlers, John Kinzie, Jack Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion, father and son mayors of Chicago, Carter Harrison, Sr. and Carter Harrison Jr., “Mr. Cub” Ernie Banks and world renowned architect Luwig Mies van der Rohe.

Other people buried here are known by the streets that have since been named after them, such as Charles H. Wacker, John Peter Altgeld and Alexander N. Fullerton.

The most beautiful grave site is located in the middle of the cemetery on a small island overlooking a tranquil pond. A simple plaque on a rock commemorates the final resting spot of Daniel H. Burnham and his wife.

It is appropriate that Mr. Burnham occupies such a beautiful location for it was his Plan for the City of Chicago that laid out the future growth and objectives for Chicago, always emphasizing its beauty. Completed in 1909, Burnham’s Plan is still the benchmark against which new plans for the city are measured.

Writing about the cemetery, Crain’s Chicago Business editor Dan Miller pinpoints the unique draw of Graceland: “It offers something every generation of American seeks — tangible evidence of an honorable history, and veneration of our ancestors.”

It also offers visitors a unique sense of Chicago, people who were primarily responsible for building the City into the great metropolis it is today.

Perhaps it is fitting, then, that the only sound that penetrates the eternal silence of Graceland is another iconic piece of Chicago’s history — a rickety, rumbling, above-ground railroad that clatters its way down the cemetery’s eastern border. Like rolling thunder, it arrives with a crash…and then slowly rumbles into the distance.

You can visit Graceland Cemetery by going on the Red Line. L Stop Tours also hosts a Chicago city tour via the Red Line that shows visitors the city’s Chinatown, Stretterville, and so much more!

Read more about Graceland Cementary: Chicago Stories, Symbols and Secrets. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.