The Great Department Stores of State Street

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Before Amazon, before smart phones and before the internet, Chicago residents shopped at Loop department stores — retail emporiums that offered a wide range of products and services to customers and patrons. Urban department stores at the time were cavernous, trendy, fashionable, service-oriented and, most of all, convenient. Everything you could ever want or need was contained within a massive, multi-story building that sprawled like a behemoth over a large city lot in the central business district.

Department stores, however, weren’t always kings of the retail hill. Before department stores became fixtures in the Loop and outlying neighborhoods, several Chicago-area retail merchandisers created thick, paper-bound catalogs that were distributed to customers across the nation. Using the U.S. Postal Service and the extensive network of railroads that converged in Chicago to ship orders, retailers with catalogs were able to create a virtual department store. They provided products and services to customers throughout the country, to shoppers who never even set foot in Chicago. Catalogs were a huge success.

Catalogs, however, did little for retail customers who wanted an in-person shopping experience — people who wanted to discuss product attributes with knowledgeable sales associates, view colorful store decorations and display windows or enjoy a gourmet lunch in one of the store’s dining rooms. This is where department stores shined and in the years following the Great Fire (1871 to 1910), department stores began to sprout in Chicago like dandelions, especially on State Street in the Loop.

The following is a list of department stores that, over the years, operated on or near State Street:

Marshall Field & Company/Macy’s

One of the most admired department stores in the world, Marshall Field & Company’s roots in Chicago go back to 1852 when Mr. Field and partner (and future hotelier) Potter Palmer opened a dry goods store on Lake St. in the central business district. Between 1892 and 1906, several buildings within the city block bounded by Randolph St. (north), Wabash Ave. (east), Washington St. (south) and State St. (west) were built over a period of time that resulted in a huge, 13-story department colossus, the new flagship store of Marshall Field & Company. The building, which stands today is the third largest store in the world, was declared a national historic landmark in 1978 and in 2005, both the company and the store were purchased by Macy’s, Inc. Macy’s continues to operate the store today but has recently reduced the store’s sales space by leasing floors 8 through 13 to a private real estate developer.

Macy’s has an entire candy section located on the lower level that sells an assortment of goodies but most notably Frango Mints – a store staple since 1918. Nowadays these delicious chocolate mints can be purchased online.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Schlesinger & Mayer/Carson Pirie Scott & Co.

In 1899, the dry goods store Schlesinger & Mayer commissioned architect Louis Sullivan to redesign its large downtown department store at 1 S. State Street where it employed over 2,500 people. When the work was completed in 1904, Schlesinger & Mayer was no longer financially able to operate the store. Rival Carson Pirie Scott & Co. moved in and occupied it for more than a century, until 2006. Today the building has been renamed the Sullivan Center — the primary retail space on the first two floors contains a Target store and the upper floors are leased to a variety of smaller businesses and not-for-profit institutions, like the School of the Art Institute. The building was designated a Chicago landmark in 1975.

Henry C. Lytton & Sons

In 1887, men’s clothing retailer Henry Lytton opened a store he called “The Hub” at the northeast corner of State Street and Jackson Boulevard. In 1913, the store moved across the street into a new, 18-story skyscraper known as the Lytton Building. After 99 years of business in the Chicago area, Lytton’s went out of business in 1986. The store building is now owned and used by DePaul University and is part of the Loop Retail Historic District.

Fair Store/S.S. Kresge/Montgomery Ward

In 1875, retailer Ernst J. Lehmann opened a department store on the corner of State and Adams Streets and called it the Fair Store. In 1897, the original edifice was torn down and a modern, 12-story department store occupied the site. In 1925, the Fair business was sold to retailer S.S. Kresge (predecessor firm of Kmart) which occupied the space until 1956. In 1957, Montgomery Ward purchased the store and occupied it until 1984, when it closed. The building was demolished the following year (1985).

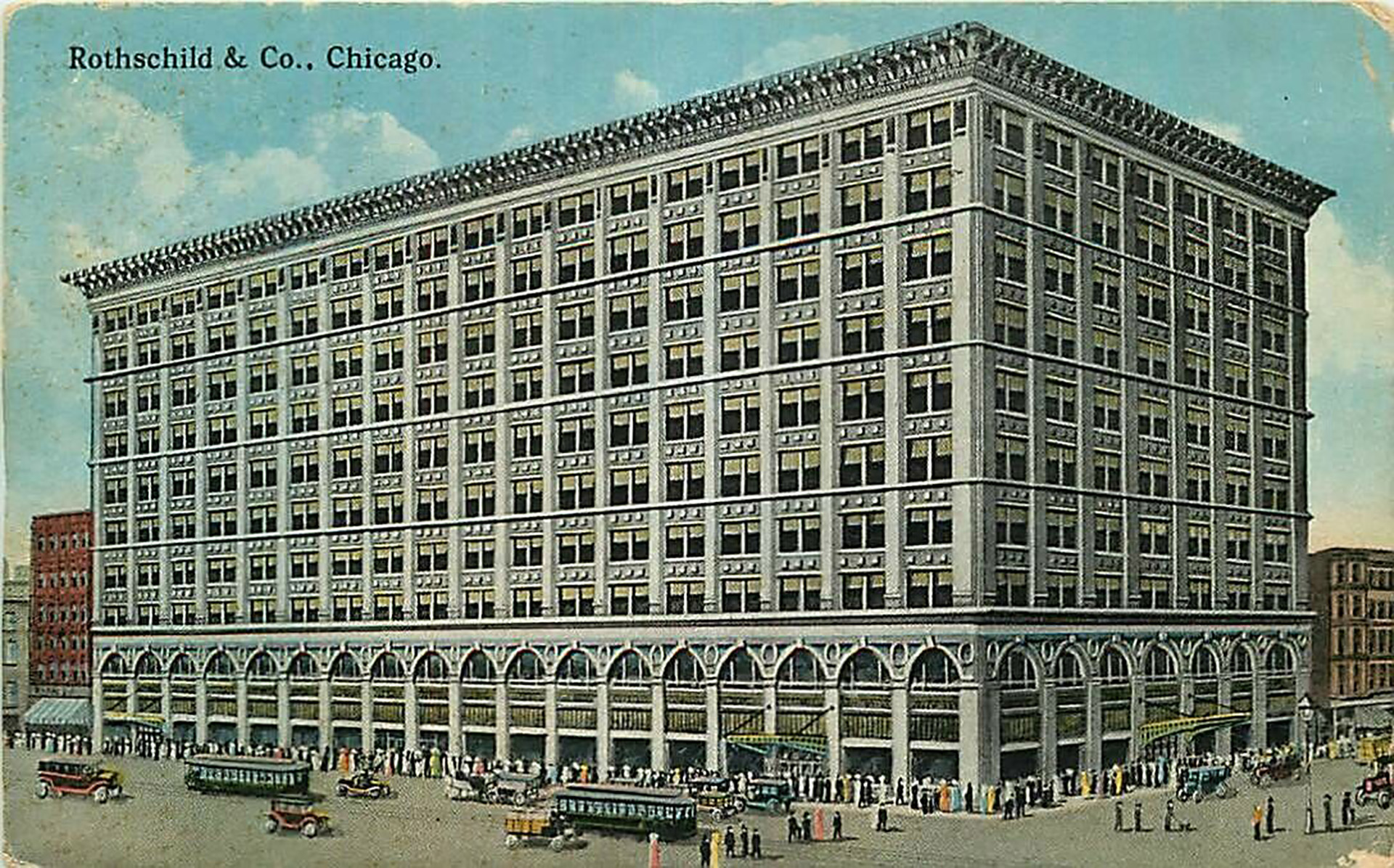

A.M. Rothschild & Co. /Goldblatt’s

Rothchild’s was a clothing-oriented department store that operated out of a constantly growing building (eventually it grew to a full city block and 8 stories) at the corner of State St. and Jackson Blvd. In 1935, discount retailer Goldblatt’s purchased the building from the Rothschilds and brought their style of mass merchandising to State St. In the 1960s, Goldblatt’s saw fierce competition from new discount retailers like Kmart, Woolco and Zayre and by 1981, the company filed for bankruptcy. It stayed in business until 2003 when the stores were closed and all inventory was liquidated. The State St. store was sold to DePaul University, which uses the building today for classrooms and offices for its South Loop campus. The building has been designated a national landmark.

Siegel-Cooper Co./Sears Roebuck

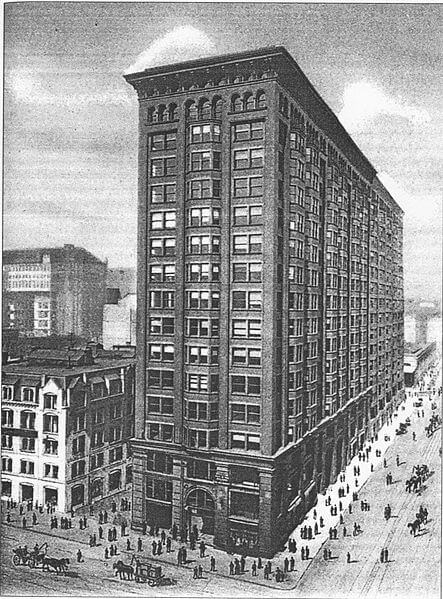

In 1891, discount retailers Siegel-Cooper moved into an eight-story building at the corner of State and Congress (now known as Ida B. Wells) Streets where they remained until 1930. Sears Roebuck and Co. occupied the building from 1931 until 1986. During that time, it was the only downtown store operated by the company — all other Sears stores in Chicago were located in distant neighborhoods, suburbs or nearby states. Designed by pioneering architect William LeBaron Jenny (he built the first modern skyscraper in Chicago in 1884), the building still stands in its original location and is occupied by Robert Morris University, which uses it for classrooms and offices for its South Loop campus.

The Boston Store

Despite its New England-sounding name, Boston Store was founded in Chicago in 1873 and eventually grew to become a 17-story department store that occupied half a city block at State and Madison Streets (2 N. State St.). With more than 20 acres of floor space, Boston Store included in its facilities a post office, a Western Union office, a savings bank, a barber shop, a first aid station, several soda fountains, restaurants, an observation tower and a cigar factory on the 17th floor. Although the company vacated the store in 1948, the building still stands today.

Mandel Bros./Wieboldt’s

After two earlier Loop stores burned down, dry goods retailer Mandel Bros. constructed a 15-story department store in 1911 on the northeast corner of State and Madison Streets (1 N. State St.). Mandel’s was the first Chicago store to have special shops for foreign goods, the first to open a children’s barber shop and the first in Chicago to display apparel on mannequin models. Budget-focused retailer Wieboldt’s acquired the Mandel store in 1960 and continued to conduct business there until 1987, which is when the then-bankrupt chain of department stores vacated the State St. property. The building stands today with mixed retail on the first floor and offices above.

Charles A. Stevens

Founded in 1886 initially as a catalog house, Charles A. Stevens & Co. grew into a retail department store with 29 locations throughout the Chicago metropolitan area. In 1912, the company decided to build its flagship store at 17-25 N. State Street, a 19-story building that cost approximately $3 million to build. An upscale fashion retailer, the store specialized in fine women’s clothing, the company closed for good in 1989. The building still stands today — the ground floor retail space continues to host a variety of women’s clothing stores while the upper floors have given way to offices and non-retail-focused tenants.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

To learn the history of famous Chicago skyscrapers, you need to go back more than 100 years. Shortly after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, the City of Chicago passed new laws that outlawed the use of wood in new building construction. This preventative measure paved the way for heat resistant materials such as brick, limestone, marble, and Terracotta tile, all of which found new popularity among local architects and building designers.

These fireproof materials lead to a boom in new construction projects, especially high-density buildings in the Loop that housed a variety of tenants. These multi-story buildings featured massively thick load-bearing walls, walls that supported the weight of the entire building above it. Because brick or stone can only support so much weight, buildings built with load-bearing walls often topped out at around 10-12 stories.

In 1884, at the height of this building boom, architect and engineer William LeBaron Jenney was commissioned by the Home Insurance Company of New York to design its regional headquarters in Chicago at the corner of Adams and LaSalle Streets. Stepping out of the load-bearing wall architectural box, Jenney supported the building with a fireproof steel frame that resembled a skeleton around the entire construction. Because the frame dispersed the weight of the building, it was much lighter than its load-bearing cousins and, thus, was able to be built taller. This innovation, experts acclaimed, made the Home Insurance Building the world’s first modern skyscraper and Chicago home to the world’s first skyscraper.

Since then, the city has become world-renowned for its architectural achievements and, of course, its vast array of famous Chicago skyscrapers.

We’ve put together a list of our favorite famous Chicago skyscrapers:

- Fisher Building

- Marquette Building

- Monadnock Building

- Old Colony Building

- Rookery Building

- Lake Point Tower

- Chicago Hilton

- Merchandise Mart

- Old Chicago Main Post Office

- Willis Tower

- Aon Center

- 875 N. Michigan Ave.

- Marina City

- Tribune Tower

- Wrigley Building

We’ve divided our list of famous Chicago skyscrapers into three groups —Pioneers, Record Breakers and Icons.

Pioneers

Fisher Building

Completed in 1896 by D.H. Burnham and Company, the Fisher Building survives today as the oldest building in Chicago that is more than 18 stories high (it has 20 floors). Its neo-Gothic design, notable for the many carvings and sculptures that decorate its terra cotta facade, was worthy of national recognition — it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. Built near the Loop’s Financial District, the building is one of the few in the area that is devoted entirely to residential apartments.

Marquette Building

Built in 1895, the Marquette Building is an early steel-frame skyscraper with masonry cladding. The building is named after explorer Father Jacques Marquette who, in 1674, was the first European settler in Chicago. What makes Marquette one of the most famous Chicago Skyscrapers is its ornate, two-story lobby which features four intricate Tiffany mosaics that depict events in Marquette’s life, including his exploration of Illinois, Native Americans he met along the way and a scene that depicts his burial. Designed by the architectural firm of Holabird & Roche, the building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1973.

Monadnock Building

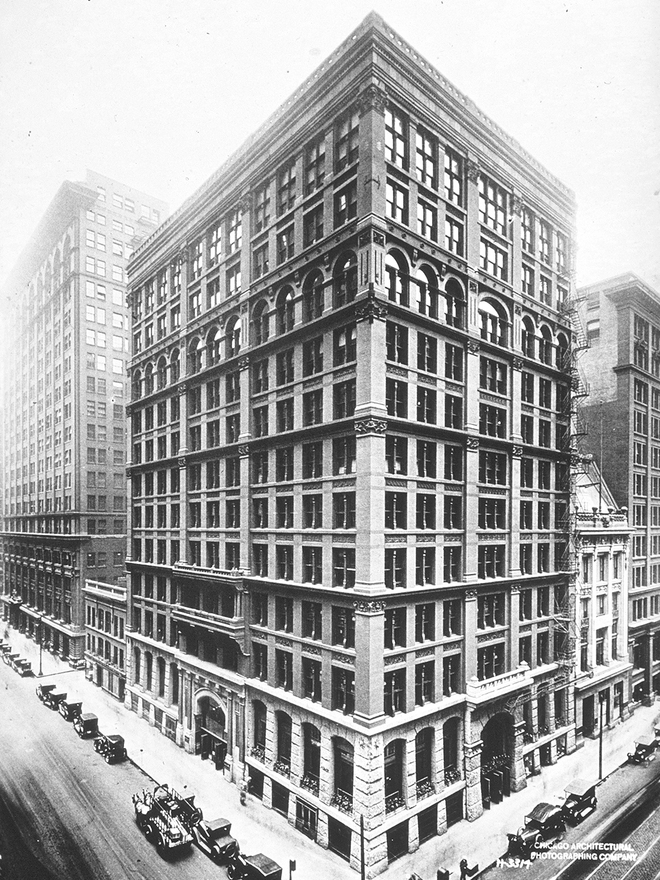

Named after a mountain in New Hampshire, the Monadnock Building was built as two separate buildings that were later joined into a single building. When it was completed in 1891, the north half of the building was, at 16 stories, the tallest load-bearing brick building in the world —the walls at its base are 6 feet thick. When the south half of the building was completed in 1893, the Monadnock Building became the largest office building in the world, featuring more than 1,200 offices and occupancy of over 6,000 workers. Known for its decorative aluminum spiral staircases and bay windows, the Monadnock Building is both a famous Chicago skyscraper and National Landmark.

Old Colony Building

Built in 1893, the Old Colony Building, named in honor of the original Plymouth Colony founded by the Pilgrims, is a 17-story structure with beautiful curved bay windows on each of the four corners of the building. Originally built as an office building, the Old Colony was converted to an apartment building in 2015 and today mainly serves as housing for college students attending school in the South Loop neighborhood. It was placed on the National Register for Historic Places in 1976.

Rookery Building

One of the most historically significant buildings and most famous Chicago skyscrapers, the Rookery was designed by the architecture firm of Burnham & Root and features a combination of load-bearing walls and an interior steel frame. It was completed in 1888. The centerpiece of the building is a stunning two-story lobby, redesigned in 1905 by Frank Lloyd Wright, with a skylight and a mesmerizing oriel staircase that visibly climbs to the 12th floor from the second. Named a National Historic Landmark in 1975, the Rookery Building also has been used in several motion pictures including “Home Alone 2” and the “Untouchables.”

Record Breakers

Lake Point Tower

This sleek, graceful, 70-story Mies van der Rohe-influenced structure was completed in 1968 and was the tallest apartment building in the world when it opened. Located adjacent to Navy Pier, Lake Point Tower is the only skyscraper in Chicago that sits on the east side of Lake Shore Drive and, given the city’s reluctance to approve any shoreline construction for environmental reasons, it is likely to stay that way for the foreseeable future. According to the developers, the shamrock shape of the building ensures that every unit in the building has a view of Lake Michigan.

Chicago Hilton

When it opened in 1927, the Chicago Hilton (formerly the Stevens Hotel) offered 3,000 rooms for guests and was, unequivocally, the largest hotel in the world. The property offered a wide variety of services and features for guests, including a miniature golf course, a concert music library, a 1,200-seat theater, a 7-chair barbershop and a small hospital with an operating room. In the past couple of decades, the hotel has been used as a backdrop for several Hollywood movies, including “The Fugitive,” “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” “U.S. Marshalls” and “Road to Perdition.”

Merchandise Mart

Built by retailer Marshall Field so he could consolidate his warehouses into a single facility, the Merchandise Mart was the largest building in the world (4.2 million square feet) when it opened in 1930 on the north bank of the Chicago River. Spanning two city blocks, the Merchandise Mart is renowned worldwide for the vast number of furniture, fabric and decorator designers that operate showrooms throughout the building. In the last several years, the building also has come to be known for “Art on the Mart,” the largest digital art projection program in the world.

Old Chicago Main Post Office

Spanning 60 acres (2.5 million square feet), the 12-story Old Chicago Main Post Office — the one that straddles the Eisenhower Expressway with a huge hole for cars to drive through — was the largest post office in the world when it was expanded in 1932 to accommodate Chicago’s booming mail needs (primarily catalogs that were distributed by Montgomery Ward, Spiegel and Sears). When the city built a new, more efficient facility in 1997, the Old Main Post Office sat idle and unused for more than 20 years. Today, it has been redeveloped and is now home to such companies as Walgreens, Uber, Ferrara Candy and PepsiCo.

Willis Tower

When the 110-story Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) was completed in 1973, it became the tallest building in the world, a title it would hold for 25 years. Today, one of the most famous Chicago skyscrapers is the third tallest building in the United States and 23rd tallest building in the world. Although Sears vacated the tower in 1995, it retained the naming rights until it sold the building in 2003. When London-based insurance broker Willis Group Holdings leased more than 140,000 square feet of office space from the new owners, they obtained the naming rights and on July 16, 2009 renamed the tower.

Icons

Aon Center

The 83-story Aon Center is the fourth tallest building in Chicago, standing in line behind Willis Tower, Trump Tower and the all-new Vista Tower. A sleek, minimalist tower clad entirely in white granite, the Aon Center takes its name from the Aon Corporation (insurance) which became the building’s primary tenant in September 2001. Completed in 1973, the building was built by the Standard Oil Company of Indiana and for many years was affectionately known as “Big Stan.”

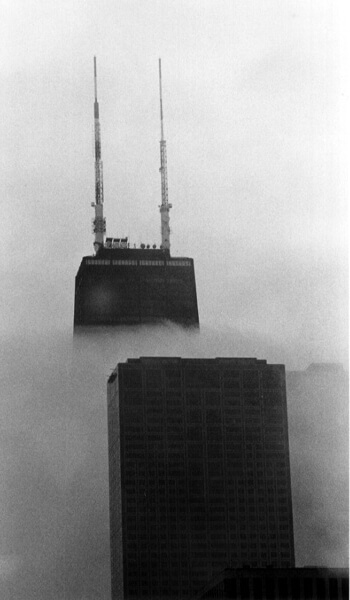

875 N. Michigan Ave.

Formerly known as the John Hancock Center), 875 N. Michigan Ave. is one of the best known — and most photographed — famous Chicago skyscrapers. A gradual taper of the building’s frame from its base to the top floor along with its distinctive X-bracing on the exterior walls of the building make it easy to identify when viewing the city’s skyline from a distance. When the building topped out on May 6, 1968, it was the second tallest building in the world; today it is the fifth tallest building in Chicago.

Marina City

In 1963, when the two towers of Marina City opened on the north bank of the Chicago River, Chicagoans thought that architect Bertrand Goldgerg’s futuristic skyscrapers were something right out of the “Jetsons.” The complex was designed to be a “city within a city” — it included a movie theater, gym, swimming pool, ice rink, bowling alley, stores, restaurants, a small adjacent office building and a marina. With 450 apartments in each tower, Marina City was the first post-war high-rise complex built in the United States and it is widely credited with beginning the residential renaissance of inner city America.

Tribune Tower

In 1922, the Chicago Tribune hosted an international design competition for its new headquarters to mark the newspaper’s 75th anniversary. The newspaper challenged architects worldwide to design “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world.” The winning entry was a neo-Gothic design by New York architects John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood that featured flying buttresses near the top. Construction on the Tribune Tower was completed in 1925 when the building topped out at 463 feet. The Tribune sold the building in 2018 to developers who plan to convert it into condominiums,

Wrigley Building

Built by the William Wrigley Jr. Company (chewing gum) from 1921-24, the Wrigley Building was the first Chicago skyscraper to be constructed north of the Chicago River (made possible by the 1920 construction of the DuSable Bridge that spanned the river at its doorstep). The building is actually two separate towers — the 30-story South Tower and the 21-story North Tower — that are connected with walkways at ground level and the third and fourteenth floors. Clad with more than 250,000 pieces of terra cotta, the Wrigley Building looks stunning when the building is bathed in floodlights at night. The spire and clocktower of the Wrigley Building take their inspiration from the Giralda tower of Seville Cathedral in Spain.

Most of these skyscrapers and more beautiful buildings and structures can be seen on a variety of our Chicago city tours. If you’d like to learn more about what tour is right for you, please contact us!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

The Cutler mail chute was not invented or manufactured in Chicago. But because it made Chicago skyscrapers more efficient and economical — and because Chicago is considered the “home” of the modern skyscraper — the Cutler mail chute, by extension, was a significant contributor to the growth of Chicago, particularly in the city’s formative years after the fire (1871).

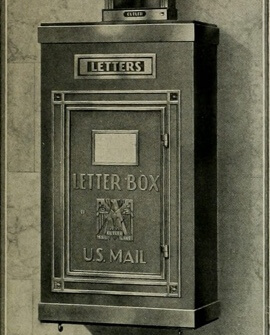

How it worked

In 1883, James G. Cutler received a patent for his letter collection system that was designed to be used exclusively in multi-story office buildings, hotels, apartment buildings and other high rise structures. In 1884 the very first mail chute and letterbox system was installed in the Elwood Building in Rochester, N.Y. Instead of traversing all the way to the building’s lobby in order to mail a letter, building occupants simply dropped mail into a glass-enclosed chute and gravity would take over. The mail would “swoosh” its way down to a box in the lobby where it was collected by postal service employees.

Why was this important? Consider an early Chicago skyscraper, the historic Monadnock Building. When it was completed in 1893, the 16-story Monadnock was the largest office building in the world, the tallest load-bearing brick building ever constructed and was one of the first buildings in the City to be wired for electricity. It featured 1,200 rooms and had an occupancy of over 6,000.

Because of its sheer size, the Monadnock Building was a postal district unto itself. It employed four full-time carriers to deliver mail to building occupants six times a day, six days per week. While this might seem excessive by today’s standards, consider that without modern and reliable communications systems (telephone systems were still in their infancy), occupants in the early Chicago skyscrapers were relatively isolated from other activities that were happening at street level and throughout the city. Timely, regular mail service was a necessity for businesses of that era — but it was also costly for the building to maintain.

Enter Cutler and his mail chute/letter collection system — the perfect solution for a huge skyscraper like the Monadnock. Not only did the system make the mailing process more convenient for tenants, it enabled the building to save time and money. Postal carriers to the building’s offices were no longer needed. Outgoing mail was now collected in a single location by a common carrier.

What about now?

Thanks to email, texting and modern mail rooms with tenant mailboxes, the mail chute has largely become a defunct letter collection device in high rises across the nation. Tenants often folded their mail so it would fit into the chute, but that only made matters worse because it would often unravel and clog the chute. Often it took days — sometimes weeks — for someone to notice that chute was clogged with old mail.

Monadnock Building

Though they have been removed from many office buildings in the last several years, it is estimated that approximately 360 mail chutes remain in use in Chicago skyscrapers nd high rise buildings. You can view two of these that are still in use on L Stop Tours’ Blue Line Tour— at the Monadnock Building and at the Fine Arts Building.

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Still a Big Hotel With a Lot of History

In the late 1920s, Chicago was known as the City of Big Shoulders, but more to the point it was simply the “City of Big.” Within its boundaries were the world’s largest office building (the Merchandise Mart), the world’s largest store (Sears Roebuck and Co.), the world’s largest livestock marketing facility (Union Stock Yards) and the world’s largest hotel (The Stevens).

In those days, apparently, everything was not bigger in Texas.

Although all of these businesses enjoyed long reigns as “the world’s largest,” all four have since given up their titles — the Merchandise Mart was supplanted in size by the Pentagon; Sears has shrunk to less than 400 stores and is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy; the Union Stock Yards have been closed 1971; and, as of this writing, the Hilton Chicago (formerly the Stevens) is only the 93rd largest hotel in the world.

Though the superlative of “World’s Largest” is no longer attached, the Hilton Chicago is still a spectacular and magnificent hotel. It oozes with history, is lavishly styled and is blessed with one of the most desirable and well-situated land parcels in the entire city of Chicago. It is across the street from beautiful Grant Park, only a couple of blocks from Lake Michigan and is an anchor property on South Michigan Avenue.

Still an Enormous Hotel

The hotel occupies a full city block with 1,544 rooms spread over 30 floors (down from 3,000 when the hotel opened in 1927). It has 1,000 employees, and an incredible 234,000 square feet of meeting and event space. It offers 36 regular suites and 13 specialty suites for guests who want a more than just a room. The suites range in size from 1,000- to 2,500 square feet and every one of them has a magnificent view of Lake Michigan.

One of the suites at the hotel, the Conrad Suite, has earned a reputation as one of the most spacious and opulent hotel suites in the world. When the hotel underwent a major renovation in 1985, two former ballrooms on the top two floors of the hotel were combined and redesigned into a single suite at a cost of $1.6 million. It has all the comforts of home and then some. The amenities include a grand salon with fireplace (1,900 square feet), a dining area for fourteen, a classic library, private kitchen, three bedrooms with full baths, two powder rooms, and four private elevators. The décor features gold and crystal Strauss chandeliers, large floral oriental rugs, mahogany parquet floors, period antique furnishing and artwork. If you can afford $10,000 per night, you can stay there as long as you wish.

The 8th Wonder: Large and Lavish

Built at a cost of $30 million, the Stevens Hotel was considered by many to be the eighth wonder of the world because of its sheer size. It was, essentially, a city unto itself. In addition to the hotel’s own private areas (heating and cooling systems, laundry, kitchens, electrical, carpentry and plumbing shops, etc.) the property featured a wide variety of services and features for guests. These included a rooftop miniature golf course, a drug store, cleaners, a children’s clothing and toy store, a beauty shop, a jewelry store, haberdashery, and flower shop. There was also a concert music library, a recreation room, a children’s playroom, several restaurants, and even a small hospital with an operating room. To top it off, the hotel had a 1,200-seat theater with “talking motion picture equipment, a seven-chair barbershop, and its own ice cream and candy manufacturing facilities.

The hotel was the brainchild of James W. Stevens, his son, Ernest, and their family. They ran the Illinois Life Insurance Company and owned the nearby La Salle Hotel. James Stevens was the grandfather and Ernest was the father of former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

From Opening Day on, the hotel was the place to be — and be seen — in Chicago. The first guest booked into the hotel was the Vice President of the United States, Charles G. Dawes; the second guest was President Machado of Cuba. Galas and special events filled the ballrooms night after night — a dinner honoring Charles A. Lindbergh; the Motion Picture Association Ball, attended by movie mogul Cecil B. de Mille and actor Victor McLagan; and many more.

But the good times didn’t last…

In the weeks and months following the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, the large hotel fell on hard times. Fewer and fewer guests booked rooms and the dining areas and ballrooms were barely used. During the Depression it is estimated that some eighty-one percent of hotels in the United States went bankrupt. In June of 1934 the seven-year-old Stevens fell victim to this trend and was declared insolvent. In 1937, the hotel was appraised for $7 million, a whopping 78 percent decrease in its value in only a decade.

Perhaps one of the most interesting eras in the illustrious history of the Stevens was launched in 1942 when it was purchased for $6 million by the U.S. Army and became the Army Air Force Technical Training School for more than 10,000 air cadets who used the hotel’s 3,000 rooms as barracks.

In February 1945, hotel magnate Conrad Hilton purchased the large hotel from a local businessman, Stephen Healy, who earlier had bought it from the Army and converted it back to a hotel. Shortly after buying the property, Hilton made improvements, which included the installation of an ice stage in the Boulevard Room that hosted elaborate ice shows nightly. Hilton also initiated extensive training sessions with his employees in an effort to become the “friendliest” hotel in Chicago.

Over the years, Conrad Hilton enticed many stars of stage, screen, sports and politics to entertain at or visit the hotel — Eddie Duchin, Guy Lombardo, John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Babe Ruth, Grace Kelly, Tony Bennett and Dean Martin, Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower, were a few of the guests he welcomed to the hotel. Hilton’s crowning achievement, however, was in 1959 when Queen Elizabeth II became a guest at the hotel.

Today’s Hilton: Still huge

In the past two decades, the Hilton Chicago has gained a reputation as a great place to film movies. Among popular Hollywood movies filmed at the hotel were “U.S. Marshalls,” “My Best Friend’s Wedding,” “Home Alone II” and “Road to Perdition.” The most memorable, however, was probably 1993’s “The Fugitive,” starring Harrison Ford and Tommie Lee Jones. In the final memorable chase scene, virtually the entire hotel is showcased. Look closely and you’ll see the Grand Ballroom, the Great Hall, the International Ballroom, a suite’s library, the roof promenade, and the hotel’s laundry.

Today, the hotel is as hip and in touch with the times as ever. It has many received several awards and recognition for sustainability programs. A large portion of the roof on the eighth floor is actually an urban garden that is cultivated in partnership with Windy City Harvest. This organization trains students how to grow organic, sustainable fruits and vegetables in an urban environment. Much of the produce is consumed at the hotel. Find the hotel when exploring the South Loop. (Accessible via the Blue Line, Green Line and Pink Line, Purple Line and Orange Line).

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Now It’s Called…

Earlier this year, the new owners of the John Hancock Building announced that the 100-story building on North Michigan Avenue will no longer be called the “John Hancock Center.” For the time being, the building will simply be known by its address — 875 N. Michigan Ave.

Nevertheless, people will still call it the Hancock Building, just as they still say “Sears Tower,” even though the building was officially changed to Willis Tower in 2009. Old habits are hard to break.

News of the name change for the Hancock Building got us thinking — what other iconic Chicago buildings have undergone name changes to the point that it’s difficult to remember its most current moniker? Here are a few we came up with:

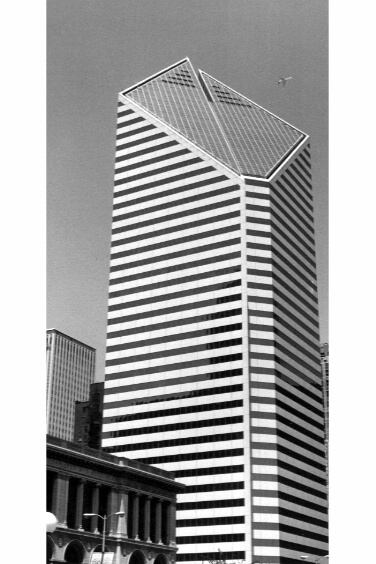

Crain Communications Building (150 N. Michigan Ave)— You’ve seen this building, it’s the one that looks like it was sliced off at the top into a diamond shape. It was built in 1984 by Associates Commercial Group and was named Associates Center, until the firm moved out in 1989. New building tenants renamed it the Smurfit-Stone Building and, later, the Stone Container Building, until 2012. That’s when Crain Communications (publishers of Crain’s Chicago Business, Advertising Age, Auto Week) relocated their Chicago headquarters into the building.

Guaranteed Rate Field (35th and Shields) — We’ve only had to live with this horrible moniker for a baseball stadium for two years (so far), but prior to that it possessed an equally horrible moniker, U. S. Cellular Field (nicknamed “The Cell” by fans). That name lasted from 2003 until 2016. In the era before “naming rights” were sold to the highest bidder, the stadiums located at this intersection (the original was across the street from the current one) were known, alternatively, as Comiskey Park (1912-1962 and 1975-2003) and White Sox Park (1910-1912 and 1962-1975).

Richard B. Ogilvie Transportation Center (500 W. Madison) — The original structure on this site was built by the Chicago & North Western Railway in 1911 and was called the Chicago & Northwestern Terminal until the station’s head house was demolished in 1997 and replaced by a 42-story office building called Citicorp Center. Later that same year, the building, which rises above the below-street-level tracks, was renamed after Richard B. Ogilvie, a former Board member of the Milwaukee Road Railroad, a governor of Illinois and the creator of the Regional Transportation Authority.

Palmolive Building (919 N. Michigan Ave.) — This beautiful Art Deco building, the one with the beacon on top, was built in 1929 by the Colgate-Palmolive-Peet Company and, for the next 36 years was known as the Palmolive Building. In 1965, Playboy Enterprises moved its editorial and business offices into the building and it became the Playboy Building, as evidenced by the huge PLAYBOY letters across the outside of the top floor. Playboy vacated the building in 1989 and for the next 12 years it was known by its street address, 919 N. Michigan Ave. In 2001, the new owners of the building decided to restore the Palmolive name, which remains in place today.

680 N. Lakeshore Drive (680 N. Lake Shore Drive) — From 1926 until 1984, this full-square-block building was known as the American Furniture Mart and it had a different address — 666 N. Lake Shore Drive. After the Mart went through some difficult financial times, Chemical Bank of New York purchased the building and immediately decided to change the building’s address. The bank said it was to distance the building from its troubled financial past; others claimed the number 666 was “cursed” and was a veiled reference to the number of the Beast from the book of Revelation. In the early 1990s, the building was converted into condominiums and has been identified by its new street address ever since.

Book one of our L Stop Tours to see these iconic Chicago buildings up close and personal.

Learn more about Chicago in the L Stop Blog

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.