Interesting Facts About Chicago’s Official Flag

According to the North American Vexillological Association, the world’s foremost organization dedicated to the study of the cultural, historical, political, and social significance of flags, there are five principles that lead to superior designs of a flag:

- Keep it simple

- Use meaningful symbolism

- Use two or three basic colors

- No lettering or organizational seals

- Be distinctive or be related to other flags

Chicago’s flag meets all of these criteria. In fact, a 2004 survey of the nation’s best city flags, conducted by the Vexillological Association, placed Chicago’s flag second in competition against hundreds of other municipal flags from cities across North America. (Washington D.C.’s municipal flag, which resembles George Washington’s coat of arms, finished first.) Not bad for a flag that was approved by the Chicago City Council more than 100 years ago and made its first public appearance a few days later (April 1917) at a car dealership in the Motor Row neighborhood on the city’s South Side.

Chicago’s official municipal flag is wildly popular. It is imprinted on virtually every city souvenir imaginable, is widely flown and displayed at buildings and residences across the city, imprinted on foods (cupcakes!) and, according to local artists, is one of the most popular designs at city tattoo parlors.

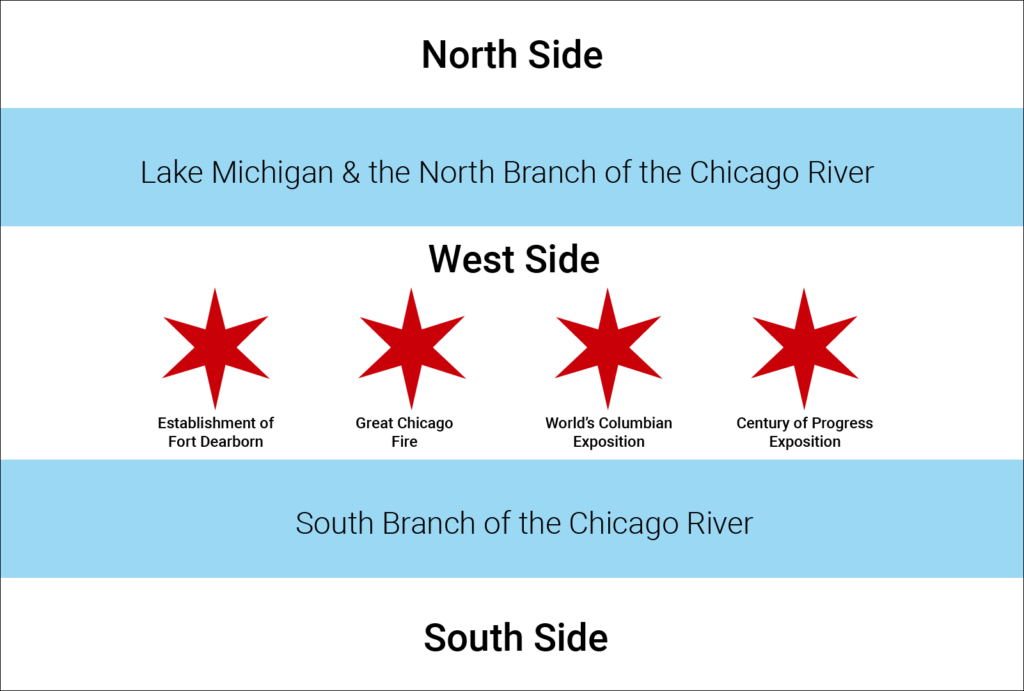

Who designed the flag? In 1915, Mayor William Hale Thompson established a municipal flag commission to review flag designs that would be entered in a contest. Poet, lecturer and author Wallace Rice was selected by the committee to develop rules that would govern the competition. Ultimately, the commission selected a design that was submitted by Rice himself. His design featured three main components — white stripes, blue stripes and six-pointed red stars — all of which symbolized key dates and facts about Chicago’s history and geographic location.

The three horizontal white stripes on the flag symbolize Chicago’s three regional sections — the top white stripe represents the North Side of Chicago, the middle white band the West Side and the lower stripe represents the South Side. Between the white stripes are two blue stripes which symbolize the water systems found within the area. The first blue stripe represents Lake Michigan and the North Branch of the Chicago River; the second blue stripe represents the South Branch of the Chicago River.

The last and perhaps most important design element of the flag are four six-pointed red stars that are centered within the widest horizontal white stripe (in the middle of the flag). The stars symbolize important dates in Chicago’s History — the establishment of Fort Dearborn at the mouth of the Chicago River (1803); the Great Chicago Fire (1871); the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893) and the Century of Progress Exposition (1933).

A commonly asked question about Chicago’s flag is why the stars have six points instead of the more popular five-pointed star. Asked why he selected six points instead of five, flag designer Rice said he hadn’t seen six points used on a flag before and thought their use would make Chicago’s flag unique.

The original flag designed by Rice in 1917 had only two red stars centered in the middle white stripe — one representing the Great Fire of 1871 and the one representing the 1893 Exposition. Rice said that he wanted to leave room for additional stars that might be added in the future. Years later, the city council approved adding the two additional stars to the flag’s design.

Will additional stars be added to Chicago’s flag in the years ahead? Stay tuned.

Chicago is a great walking city — even if you’re walking underground.

With Chicago’s Pedestrian Walkway system (Pedway), a six-mile system of underground tunnels, pathways and connected corridors, it’s possible to walk from one side of the Loop to the other without encountering traffic, nasty weather, special events or other obstacles. The uncrowded, roof-protected, climate-controlled Pedway is the way to go. It is one of Chicago’s unique “hidden” gems.

And it takes you to a lot of interesting places. The following is a list of highlights encountered on our company’s Pedway tour throughout downtown Chicago:

Small Retail Shops

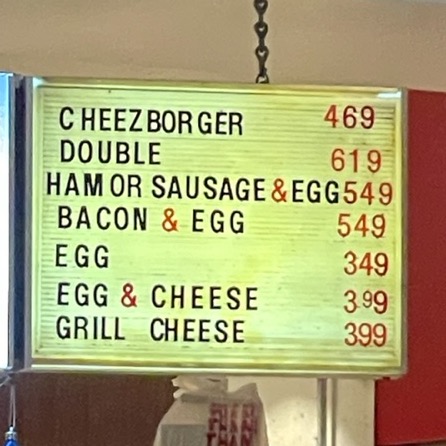

One of the delights of the Pedway is that some corridors feature a wide array of small retailers — a grilled cheese sandwich stop, a small tavern, doughnut shops, shoe repair, convenience stores, barber shops, and beauty salons. If you enjoy the look and feel of small-town America, these sections of the Pedway are for you.

Fitness Centers

A handful of fitness centers/clubs are accessible via the Pedway. At Randolph and Wabash is an LA Fitness with an indoor swimming pool that is accessible from the Pedway. In the Lakeshore East neighborhood (east of Michigan Ave. and north of Randolph St.) is the Lakeshore Sports and Fitness Club.

Macy’s Chicago

Macy’s Loop store, the second largest department store in the U.S., embraces the Pedway with four separate entrances at the sub-basement level, as well as a collection of 22 stained-glass windows that face the entrances on the opposite wall. In addition to shopping, Macy’s offers the iconic Walnut Room (the nation’s oldest continuously operating department store restaurant) and a Tiffany-designed tile ceiling with 1.6 million pieces of iridescent glass that is not to be missed.

City Hall/Cook County Building

If you have official business to take care of, the Pedway also goes to the City Hall/Cook County Building (Clark and Randolph Sts). While you’re there you can get a lot of things done (especially if you don’t have to carry your heavy winter coat around). You can visit Chicago’s mayor (if you’ve got enough clout to get past the guards in the lobby), pay your property taxes, apply for a liquor license, marvel at the fancy decor of the building, or get married. That’s right, get married. They’ve been marrying couples at City Hall for more than 100 years at Marriage Court, located on the Pedway at the north end of the building. If you time your visit just right, you may be asked to serve as a witness by some lovestruck couple.

Millennium Station

The Pedway enters Millennium Station (formerly Randolph St. Station) in different spots, including lower Michigan Ave., the Prudential Building and the Cultural Center. If you need to catch a commuter train to Chicago’s southern suburbs or the South Shore Line to Gary or South Bend, Indiana, Millennium Station is your destination. A wide variety of food and beverages are available here for hungry, thirsty travelers.

AMC Dine-In Movies

If you’d like to watch a movie and get a bite to eat at the same time, take the Pedway to the Block 37 building (Washington and State Sts.) and head toward AMC Dine-in Movies, one of several entertainment options connected to the Pedway.

Cultural Center

The easiest way to enter the Cultural Center from the Pedway is to find the “golden elevator,” and take it up one floor to the lobby of the building. In addition to art exhibits, concerts, lectures and special events, the Cultural Center (Randolph St. and Michigan Ave.) is home to the world’s largest Tiffany Dome, as well as a second dome commissioned by the Grand Army of the Republic when the building was built (1895).

Red Line/Blue Line

Chicago’s two busiest L lines — the Red Line and the Blue Line — are not elevated when they pass through the Loop. They are subways that run parallel to one another one block apart (on State St. and Dearborn St. respectively). In 1951, two tunnels were dug between the two lines to enable passengers to cross from one line to the other. These tunnels became the first sections of Chicago’s Pedway and also served as inspiration for the construction of the entire system. To this day, these original Pedway tunnels are still in use, serving CTA passengers and Pedway walkers alike.

Chance the Rapper

Don’t miss a Pedway mural painted by student artists from the School of the Art Institute on lower Randolph St. (near Wabash). The artists were asked to select a contemporary who was up and coming in the performing arts and include him/her in the mural. They selected a then little-known artist — Chance the Rapper — now a global superstar who calls Chicago “home.”

Daley Plaza

If you exit the Randolph St. Pedway at Dearborn St. by ascending the adjoining greystone stairs, you’ll find yourself in the middle of Richard J. Daley Plaza, home to several Chicago landmarks. Note the iconic, untitled sculpture by Pablo Picasso, a statue on Washington St. by Joan Miró, the Richard J. Daley Civic Center (offices and courtrooms) and the First United Methodist Church at Chicago Temple, a 23-story Gothic-style building which houses “Chapel in the Sky,” the world’s highest place of worship.

Lakeshore East Hotels

East of Michigan Ave. and north of Randolph St. is a newer city neighborhood known as Lakeshore East. If you’re interested in staying in a hotel that’s connected to the Pedway, this neighborhood has a wide array from which to choose — Swissôtel, Hyatt Regency, Fairmont, Radisson Blu Aqua and the St. Regis.

Amazon Go

Located in the Pedway beneath the Prudential Building, Amazon Go allows you to purchase items without having to wait in line to check out. All you need is your phone and the company’s app — you select your items and then simply walk out of the store. It’s hassle free and convenient — just like the Pedway.

Harris Theatre

If you want to see a show and don’t want to travel outside to get there, take the Pedway east to Randolph St. and visit the Harris Theatre, Chicago’s home for music and dance productions of all types. The Harris Theatre is located at the north end of Millennium Park.

Nicknames for large American cities are a mixed lot. Some are treasured and well known (The Big Apple for New York), some are functional (The Motor City for Detroit), some are descriptive (The Big Easy for New Orleans) and some are reviled by their own residents (Frisco for San Francisco).

Chicago has had a number of nicknames since its early days as a trading post along the shores of the big lake. Like the nicknames for other cities listed above, some of Chicago’s nicknames are well-known, some are descriptive, some are clever, and some are not well-liked or even used by locals.

Let’s take a closer look at the origins of some of Chicago’s better-known nicknames:

The Windy City

In terms of actual average daily wind speed, Chicago doesn’t even rank among the top 20 windiest cities in America. So why does it own the nickname “The Windy City?” The answer has to do with politics and not meteorology. Because Chicago rebuilt itself so quickly after the Great Fire of 1871, city fathers were eager to show off the new city to the rest of the world so they decided to enter the competition to serve as host for the 1893 World’s Fair. New York, which also wanted to host the Fair, said Chicago’s boasts about their new city were nothing more than hot air coming from a bunch of political windbags. The name stuck and the rest is history. By the way, Chicago bested New York and went on to host one of the most successful World’s Fairs on record.

Second City

Again the Chicago Fire plays a key role in the development of one of the city’s best-known nicknames. In 1871, with the city in ruins, local residents remained firm in their resolve to rebuild the city a second time — thereby creating a Second City. Eight years later the nickname was co-opted by an East Coast newspaper columnist who used the nickname to describe what he felt was Chicago’s second-class status to New York. In 1959, Chicago’s newest improvisational theatre group adopted the nickname for their comedy troupe and theatrical productions, calling themselves “Second City.”

City of Big Shoulders

In 1914, Carl Sandburg wrote a poem entitled “Chicago” in which he describes it as the “City of the Big Shoulders.” Sandburg is referring to working class people — tradesmen and physical laborers — who built Chicago into the great city that it is. He also is referring to Chicago’s importance to the nation as a provider of meat and food products, transportation, inventions, and so on. His nickname resonated with Chicagoans and non-Chicagoans alike and today is often used in speeches by politicians and civic boosters.

Chi-Town

Though it has been around for a long time (its first recorded use is in a local newspaper circa 1900), many locals dismiss the nickname as something lame that is uttered only by suburbanites and tourists. They say the nickname isn’t edgy, is similar to other cities’ nicknames that use “town” to describe themselves, and it doesn’t even align with the correct pronunciation of the city’s name (a long “i” sound instead of a short “i”).

Chi-Beria

Richard Castro, a meteorologist working for CBS television in Chicago in 2014, became famous overnight when he combined the words “Chicago” and “Siberia” to describe some of the coldest temperatures encountered by Chicagoans in decades, hence Chi-beria. Today, Castro’s term is used to describe much colder-than-normal weather conditions in and around the city.

City in a Garden

Chicago’s motto, adopted in 1837 when it was incorporated as a city, is Urbs in Horto or “City in a Garden.” The motto, which appears on the official seal of the City of Chicago, was meant to commemorate the many green spaces, parks and beaches that preceded Chicago’s founding as a city. Over the years, thanks to such visionaries as Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmstead and Jens Jensen, Chicago’s park system and public green space areas have become the envy of other municipalities around the world.

That Toddlin’ Town

First published in 1922, “Chicago (That Toddlin’ Town)” was a song that was performed and recorded many times but didn’t hit the charts until Frank Sinatra recorded it in 1957. It has been one of the city’s unofficial nicknames ever since. What does “toddlin'” mean? There was a popular dance in the 1920s called the Toddle and Chicago was well known at that time as a “dancin’ sort of town.” The nickname was a good fit.

My Kind of Town

In 1964, Frank Sinatra and his fellow rat packers starred in a feature film entitled “Robin and the 7 Hoods.” In the film, Sinatra’s character is let out of jail and he gratefully sings his tune of thanks to a gathered group of Chicagoans, stating emphatically that the city is his “kind of town.” Over the years, the nickname has scored big with Chicago’s tourism agencies who have relied on the phrase several times to promote the city in marketing campaigns.

The Third Coast

The Third Coast is a term that refers to coastal areas in the United States that are distinctly not the East Coast or the West Coast. While the Gulf Coast of the United States most often receives the moniker “Third Coast,” the Great Lakes region — and more specifically Chicago — sometimes get the honor. In 2013, author Thomas Dyja wrote a book, The Third Coast: When Chicago Built the American Dream, which also helped popularize the nickname.

The White City

For the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, pavilions and exhibition halls were purposely constructed as temporary facilities and then painted white with pressurized sprayers. The net result was a collection of glistening white buildings fronted by reflection pools and lagoons — a veritable “White City,” which is how the nickname originated. It is rare, however, that you hear one refer to today’s Chicago as the White City because it was so long ago that the White City existed. One nickname that did stick from the Fair, however, was “Monsters of the Midway.” The Midway refers to the Midway Plaisance, a separate area for fair amusements, rides and sideshows that captured the hearts and minds of fairgoers. Because the event was held on land that would later become the University of Chicago campus, the University’s powerful football team, the Chicago Maroons, became known as the Monsters of the Midway.

The City that Works

Mayor Richard J. Daley bestowed this nickname on the city in a speech when he described Chicago as a blue collar, hard-working city which ran relatively smoothly. Recently, many have added a question to the phrase: “…Works for Whom?”

The Great American City

In his book about the presidential nominating conventions of 1968, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Normal Mailer wrote, “Chicago is the great American city … perhaps [the last] of the great American cities.” In 2012, Robert Sampson wrote Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood. Both authors felt that Chicago was a classic city in the American sense — much more so than others, like New York, which they argued had outgrown its greatness.

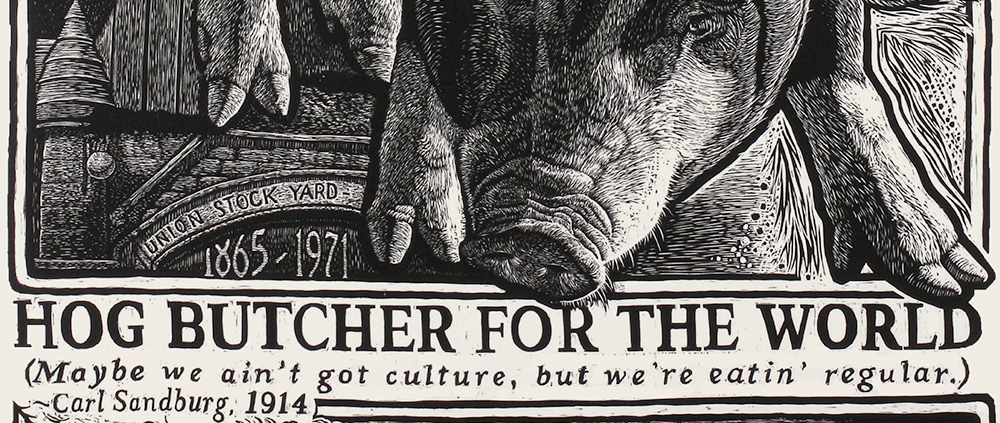

Hog Butcher to the World

Widely used for more than 100 years, the nickname has fallen out of favor since the Union Stock Yards closed in 1971. When it is invoked, it is generally by people who use it in a nostalgic sense — an era when meat packing was the city’s largest industry and had achieved world-wide recognition for its size, efficiency and contributions to Chicago’s growth and prosperity. The nickname first appears in Carl Sandburg’s 1914 poem, “Chicago.”

Beirut by the Lake

When Harold Washington was elected mayor in 1983, his block of aldermanic supporters in the City Council numbered 21, but his opposition, led by the “Two Eddies” (Aldermen Edward Vrdolyak and Edward Burke) thwarted Washington’s agenda at virtually every turn. Dubbed “Council Wars” by the local media, the legislative gridlock became known as “Beirut by the Lake,” a reference to the Lebanese Civil War of the 1980s.

Chicagoland

Though the actual first use of this nickname is a bit murky, Col. Robert McCormick, editor and publisher of the Chicago Tribune, generally is given credit for first use of the coined phrase on page one of his newspaper on July 26, 1926. The term Chicagoland refers to the entire Chicago metropolitan area, including 14 counties in Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

A Brief Timeline

Billy Goat Tavern, one of Chicago’s most unique and best-known bars, has had a number of famous “moments” in its long and illustrious history. Many are legendary

- A goat falls off a passing livestock truck in 1934 and is adopted by near West Side tavern owner Bill Sianis, who decides to grow a goatee and change the name of his bar. Billy Goat Tavern is born.

- Sianis and his goat are denied admission to the 1945 World Series at Wrigley Field against the Detroit Tigers because the goat “smells.” Sianis casts a curse on the Cubs and, when they promptly lose the series to the Tigers, sends a note to Cubs Owner P.K. Wrigley saying, “Who smells now?”

- In 1964, Sianis moves his tavern to its present location, 430 N. Michigan Avenue, Lower Level.

- A short sketch about a Greek diner resembling Billy Goat Tavern appears on NBC-TV’s Saturday Night Live on January 28, 1978. Overnight, the tavern becomes a “must-see” destination for locals and tourists.

- On April 29, 1997, Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper columnist and number one Billy Goat Tavern booster Mike Royko dies at age 64.

I didn’t happen to be at the bar when any of these illustrious moments occurred, however, I’ve frequented the pub enough over the years to be deemed a regular and, as such, have experienced a number of great moments of my own in that wonderful den of iniquity.

Why am I a regular? The primary reason is because I have worked in the Streeterville neighborhood since 1974 and Billy Goat Tavern has always been a convenient but off-the-beaten-track bar where one could enjoy a couple of beers without being pestered (at least in the early years) by tourists. The other reason I hung out at Billy Goat was because I was a journalist and we all know that journalists like to hang out with other journalists at bars and listen to each other’s stories about what it’s like to be an ink-stained wretch. I was no exception.

Another Perspective

What are my greatest moments in Billy Goat’s over the years? I’m glad you asked — I’ve listed them in reverse order below:

10) The “Back” Room

A group of us — “young Turks,” as our boss labeled us — worked in a skyscraper that towered over Billy Goat’s like Wilt Chamberlain standing next to Mini Me. A quick elevator ride down to street level and few steps (maybe thirty?) put us in front of the famous “Butt in Any Time” sign at the entrance of the pub. It was easily the closest bar to our office. And because our office closed earlier than most, we were generally the first after-work revelers to descend on Billy Goat’s on Fridays for cocktails (4:01 p.m.). Being early allowed us to commandeer the back room (now called the VIP Room) and have it mostly to ourselves for an hour or two. Between 1980 and 1986, we solved all the world’s problems over cocktails in that location.

9) My Farewell Party

In 1986, I announced that I was leaving my job as director of communications for a Michigan Ave. firm and starting my own consulting business. Fellow employees put together a farewell party, replete with gag gifts and other paraphernalia. I remember one of the gag gifts distinctly — an actual cow’s tongue that was wrapped in cellophane. (The gag worked because a lot of us worked in the meat business at the time.) I momentarily put the gift on top of the Billy Goat’s serving counter to remove another item from my briefcase. At Billy Goat’s, the sight of a real cow’s tongue on a serving counter didn’t even register a blip among nearby patrons or employees. As a matter of fact, I think one of the employees asked me, “You want cheeps with that?”

8) Drinking With the Pressmen

Back in the day, Billy Goat’s was not just for journalists, it attracted second and third-shift newspaper employees who worked late into the night printing Chicago’s daily newspapers. One night, a friend and I found ourselves downtown after midnight and we decided to go into the Goat for a quick one (or two). Seated next to us at the bar were two pressmen from the Chicago Sun-Times who regaled us with printing stories and offered to give us a tour of the presses at some point in the future. I don’t think I could have ever had that experience at any other Chicago bar. Thank you, Billy Goat.

7) Nanny & Billy

The Womens’ and Mens’ toilets at Billy Goat have always been labeled “Nanny” and “Billy.” For some reason, this confuses tourists and other first-timers who don’t know which was the correct one to go in — so they’d ask us (when we were sitting nearby) and we’d tell them. “Nanny is a young male goat and Billy is grown one.” That was wrong, of course, but it was fun to look at the expressions on people’s faces as they sheepishly came out of the incorrect bathroom and scooted over to the correct one.

6) My First Legal Beer in Illinois

Like many other states at the time, Illinois lowered the legal age to purchase beer and wine to 19 in 1973. I turned 19 in September of 1974 and when I returned home for Christmas break from college, I started an internship at a Streetervillle public relations firm (on Erie St.) that was only a short walk to the Goat. Fortunately, my boss and several co-workers sensed the magnitude of my personal milestone and treated me to lunch where I washed down a double cheeseburger with a mug of Schlitz. It was December 20, 1974 — I was legally an adult and a Goat “virgin” no more.

5) My Colleague Gets a Beer Dumped on Him

One of the guys I worked with at the Michigan Ave. firm had a penchant for saying wrong things to women he tried to flirt with. One evening a group of us were in the back room when suddenly a woman from our group stood up, called this guy a “disgusting pig” and, with the flourish of a symphony conductor, dumped a full mug of Schlitz on the offender’s head. Funny? Yes. A waste of a good beer? You be the judge.

4) Consecutive Cheeseburgers Streak Comes to A Halt

It was about noon on a Wednesday in 1983 and I was feeling a little peckish, so I decided to pop down to the Goat for a beer and something to eat. I don’t know what got into me. I decided on the fly that for the first time in more than 10 years I was going to order something different to eat — no double cheeseburger for me today. When the grill cook (who knew me) looked at me and asked, knowingly, “Dobla Cheez?”, I surprised him and said, No. Give me a Grilled Ham and Cheese.” He looked at me strangely for a second and then said, “OK.” I enjoyed the sandwich but started a new cheeseburger streak two days later.

3) The Crack of Dawn

Her name wasn’t Dawn and I don’t even know what his name was — but neither of these tidbits matter. What’s important (at least to this blurb) is that my companion and I were enjoying a cocktail when suddenly I notice her edging her cell phone camera into position for a photo. I asked her what’s going on and she “shushes” me to be quiet with her index finger over her lips. I look over my shoulder to see what is so picture-worthy and I see a man and woman sitting at the bar with their backs to us. He is attempting to put his arm around her waist and she has a pair of shorts on with a plumber’s crack that is revealing a colorful tattoo and at least half a moon. I consider telling the couple about the “Butt In Any Time” sign at the entrance to the tavern but decide it’s probably best to keep that information to myself.

2) The French Chef Visits Billy Goat

In 1979, a group of my colleagues convinced Julia Child to become a judge at the National Beef Cook-Off in Omaha. While there, our group told Julia about the Billy Goat and how it was the closest bar (and grill) to our office. She said that she would like to visit and would let us know when she planned to go there. On June 1, 1981, she called our office and said she was going to visit Billy Goats the following day and did we want to join her? Of course we did — it was kind of like the Queen of England slumming with a visit to White Castle. It’s something you just have to witness in person. Like everyone else, Julia loved Billy Goat’s and especially the cheeseburger. “I could live on this forever,” she said.

1) Royko Gets His Comeuppance

A friend and I were enjoying beers at one of the front tables. Sitting no more than two feet away (at the next table) was Mike Royko and a colleague. My friend decides he must say something and interrupts Royko’s private conversation. He tells Royko how much he loves his column, praises him for being great writer and for being a Billy Goat’s booster. Royko, hearing my friend’s accent, says “You must be from New York. I can hear it in your words.” My friend denied being a New Yorker and threw him more flattery. Royko asked again, “Aren’t you from New York? Where are you from?” My friend looks him right in the eye and says, “I’m not from New York. I’m from Brooklyn.” Knowing he’d been roped into a trap, Royko ceased all conversation, motioned to his friend and the two of them got up and left. Even though he was a celebrated Pulitzer Prize winner, he should have known — a Brooklynite will never admit to being a New Yorker.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

As a civilization, the Roman Empire lasted for 1,000 years. In 2022, Chicago will celebrate the 185th anniversary of its founding.

Like Rome, Chicago has created a number of important structures and monuments that not only have enjoyed tremendous success over the years but have survived and withstood the test of time. They are stable and popular structures and institutions…none are likely to disappear any time soon. Wrigley Field, the L, the Art Institute, O’Hare Field and McCormick Place are a few examples that come to mind.

On the other hand, Chicago also is home to a great number of municipal “dinosaurs” — well-known buildings, institutions and other local treasures that, thanks to a rapidly changing world, have suddenly become outdated, irrelevant and, possibly, unneeded in the future. Like the dinosaurs of era past, these local treasures are endangered species and may soon become extinct.

L Stop Tours has put together a list of Chicago “dinosaurs” for your consideration:

U.S. Post Office Loop Station

211 S. Clark

In a day and age when wireless communication is omnipresent, do we really need an over-large U.S. Postal Service building to handle an ever-dwindling amount of U.S. mail? The Old Chicago Main Post Office, a 2.5 million-foot behemoth on West Harrison Street, built in 1921 and decommissioned in the 1980s, was recently remodeled into new executive offices for such companies as Walgreens, Ferrara Candy Co., Pepsico, Cisco and Uber. A few blocks to the east, the Loop Station Post Office, a beautiful structure designed by famed architect Mies van der Rohe and built in 1974, seems destined for a similar fate. How long will this oversized postal snail mail facility occupy valuable Loop real estate that may be better suited for something else? Stay tuned.

Chicago Board of Trade

141 W. Jackson Blvd.

Established in 1848, the Chicago Board of Trade is one of the world’s oldest, largest and most successful futures and options exchanges, dealing in a wide range of futures contracts for livestock, agricultural commodities, world currencies, energy products and much more. For the first 150 years of its existence, the Board of Trade and its parent company, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME Group), traded futures and options via the “open outcry” system. This methodology featured traders who stood in amphitheater-style “pits” and yelled their orders to others, thereby creating a “live” market for futures contracts. This method required the Board to maintain huge trading floors with plenty of space for the pits, traders, runners, brokers, huge electronic “scoreboards” on the walls surrounding the trading floor, and much more. In 1994, the Board of Trade began to convert its trading platforms from open outcry to electronic trading. By 2015, the Board of Trade had closed most of its trading pits and ushered in the era of online trading. With no need for huge trading floors or adjoining office space, the CME Group sold the building to a consortium of real estate companies and leased only a fraction of the building’s office space that it needed for operations. With the pandemic slowing the return of office workers to the Loop, the building is emptier than ever before, an abandoned tower in the midst of Chicago’s busy financial district. It begs the question — what is the future of futures trading at the Board of Trade?

Harold Washington Library Center

400 S. State Street

Chicago needed a new main library and in 1991 it got one, the Harold Washington Library Center, a 10-story 750,000 square foot library facility with beautiful marble walls and floors, wood paneling throughout and a state-of-the-art lighting system. In less than 10 years, however, the new, massive library already was beginning to look like a dinosaur. Why go to the library when research could be conducted on a computer at home? Why go to the bother of checking out a book and returning it at a preordained time when you can purchase it cheaply on a computer or smartphone and read it wherever you go on your favorite reading device? Chicago has an excellent system of branch libraries serving neighborhoods throughout the city. Do we still need a huge central library serving a downtown business district that, because of lingering effects from the pandemic, is still bereft of workers, tourists and residents?

Macy’s

111 N. State Street

For well over 100 years, Marshall Field and Company and, later, Macy’s, operated a 14-story department store that occupies a full city block in the heart of the Loop. A throwback to the big department stores of the 1930s and 40s that catered to every possible need of urbanites, Macy’s State Street Store is no longer the retail powerhouse that it once was. In fact, the store is shrinking — in 2018 Macy’s sold the upper half of the building (floors 8-14) to an asset management company which, in turn, is leasing the space to corporate tenants. The parent company of Macy’s also is downsizing and reducing the company’s presence in Chicago. In 2021, Macy’s permanently closed its Water Tower Place store on the Magnificent Mile, a location it had occupied for 45 years. The last of its kind — a massive, expensive-to-operate, downtown-anchored department store — Macy’s State Street store appears to be living on borrowed time.

Soldier Field

part of the Museum Campus

Opened in 1924, Soldier Field has hosted a wide variety of sports teams and events over the years, including the Chicago Bears of the National Football League, the Chicago Fire of Major League Soccer, major college football games, heavyweight boxing matches and a variety of concerts and stage shows. Soldier Field has a football capacity of 61,500 and is the oldest and smallest stadium in the National Football League. This small size is one of the reasons its future is tenuous — the Bears recently announced that they might leave Soldier Field for a stadium they would build on a parcel of land that presently houses the former Arlington Park Race Course in Arlington Heights. Such a departure would leave Soldier Field without its marquee tenant — and its future very much in doubt.

Manually-Operated Elevators

Fine Arts Building, 410 S. Michigan Ave.

The elevator was invented in 1853 by Elisha Graves Otis and introduced at the Crystal Palace Convention in New York City. For the next 90 years, most elevators in the U.S. had operators who opened the doors, guided the speed of the car between floors, leveled the car at each stop and announced destinations at each floor for riders. By the mid-1960s, most elevators in the U.S. became automatic, riders pushed buttons to ascend or descend to their destinations, operators were no longer needed. Today, there are approximately 22,000 elevators in the city of Chicago and only one set of manually-operated elevators — they are located in the 138-year-old Fine Arts Building on South Michigan Ave. If you miss the human touch that once came with a simple elevator ride, or if you’ve never ridden a manually-operated elevator, head over to the Fine Arts Building — before something “automatic” takes its place.

South Shore Line

Millennium Station, 151 N. Michigan Ave.

In 1915, interurban railroads were an extremely popular mode of city-to-city transportation with more than 15,000 miles of track connecting urban areas across the country. Essentially beefed-up streetcars that ran long-haul routes through suburbs and rural areas on their way to other urban areas, interurbans were so popular that they had grown to become the fifth largest industry in the United States. But interurbans didn’t last. Paved roads and interstate highways made cars and trucks more popular than trains and the interurbans began to fold and go out of business. By 1930 most of the interurban railroads had vanished; by 1960 only four remained in the entire country. Today there is only one remaining interurban railroad operating in the United States, the South Shore Line, which has been operating electric trains between downtown Chicago (Millennium Station) and South Bend, Ind. (86 miles) since 1905. The only Chicago area commuter railroad not a part of Metra (the Chicago area’s commuter rail agency), the South Shore Line continues to go it alone and, at least for now, continues to survive as the last of its kind.

Greektown

Halsted and Jackson

There was a time when Chicago had two separate Greektowns, the original in the West Loop (Halsted St. and Jackson Blvd.) which dates to the late 1940s and “New Greektown” on the North Side (Lawrence Ave. and Western Ave.) which was popular from 1975 to 2000. New Greektown didn’t stand the test of time. Greeks who moved there to start businesses, night clubs and restaurants decided to move to the suburbs when rents in the neighborhood no longer were affordable. That left the original Greektown as the sole surviving Hellenic community in Chicago. But Chicago’s original Greektown also has steadily shrunk in size over the past two decades. Explosive growth of Fulton Market and West Randolph Street restaurant and entertainment district has led to urban renewal and gentrification of the entire West Loop. Huge apartment and condominium towers now stand where Santorini, Rodity’s, Parthenon, Pegasus and other stalwart Greek restaurants once plied their trade. Greek grocery stores and retail businesses have vanished as have many Greek residents, most of whom have long since moved to other neighborhoods in the city and suburbs. While a speck of the old neighborhood remains — the Greek Islands restaurant still is in business and the National Hellenic Museum continues to celebrate the history and culture of the neighborhood — most of Chicago’s original Greek neighborhood has fizzled out faster than the flames on an order of saganaki. Why is the neighborhood disappearing? It’s Greek to us.

16-inch Softball

Softball was invented in Chicago at the Farragut Boat Club in 1874 when a wadded-up boxing glove was hurled at a “batter” who swung at it with a stick. The result was a new sport — 16-inch softball, a game played without a fielder’s glove. Over the years, 16-inch softball grew to be the summertime recreational sport of choice for adults throughout the Chicago area. Every city and suburban park or park district sponsored leagues that had waiting lists of teams waiting to play. Today, the popularity of 16-inch softball has faded considerably. Millennials view it as an old man’s sport, women prefer 12-inch softball (with gloves) and softball is no longer the only summertime league in town (today there are many other sports and recreational activities that compete with softball). Yes, you can still watch or play 16-inch softball in Chicagoland, but with each passing year, it is getting more difficult to do so.

Chicago Beaches

Because the water level of Lake Michigan has been increasing for a number of years, Chicago’s beaches have been getting noticeably smaller, thanks to erosion and sediment displacement. In fact, some of Chicago’s beaches have disappeared completely. Juneway and Fargo beaches on the North Side (in Rogers Park) are submerged underwater and a steady drumbeat of crashing waves have collapsed revetment projects that were designed to protect the shoreline. Other popular beaches — Oak Street, 12th Street, 57th Street, North Avenue — are only a fraction of the size they used to be —thin strips of sand with barely enough space for a row or two of beachgoers. A crashing meteor may have brought an end to dinosaurs on earth; climate change may be doing the same thing to today’s Chicago’s beaches.

Non-Multiplex Movie Theaters

There’s only a handful of historic, non-multiplex movie theaters remaining in Chicago — Logan Theatre (2646 N. Milwaukee Ave.), Music Box (3733 N. Southport Ave.), Davis Theater (4614 N. Lincoln Ave.) and a few others. These old-time movie palaces generally have only one or two screens (unlike the multiplexes) and often book old, seldom-screened movies or smaller concerts or live staged events. With the rise of streaming services and other at-home entertainment options, the lingering effect of the pandemic on social activities (like seeing a movie) and the high cost of maintaining older, historic facilities, the continued survival of these institutions appears as though it will be a limited engagement.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

For more stories about Chicago’s fascinating history, take a look at what Chicago city tours we are currently running! L Stop Tours runs unique tours all across Chicago’s neighborhoods that are guided by lifelong Chicago residents. Discover the amazing architecture, tasty food, and interesting tidbits about the city in one of our Chicago walking tours!

Although Chicago is commonly known as the “Second City,” it’s equally known as a city of “firsts.”

Unfortunately, we’re not referring to the success of local sports franchises. The “firsts” that we’re talking about are things that were invented in Chicago or the metropolitan area. Many of these inventions are celebrated widely in the media — the Ferris Wheel (1893 World’s Fair), deep dish pizza (Pizzeria Uno in 1943), the brownie (Bertha Palmer and the Palmer House, 1893), the world’s first modern skyscraper (Home Insurance Building, 1888) and Playboy magazine (Hugh Hefner, 1953).

Many of Chicago’s other firsts, however, are not as well known. So, in our never-ending quest to shed a spotlight on all things Chicago, we’ve compiled a list of lesser-known Chicago inventions or “firsts.” Here they are in no particular order:

Blood Bank

After observing the difficulties experienced by World War I soldiers who needed a certain blood type for a transfusion, Bernard Fantus, a Chicago physician came up with a better idea. He developed a method of blood preservation and storage that allowed patients to access blood without waiting for a donor. The nation’s first blood bank opened at Cook County Hospital in 1937.

Spray Paint

Although aerosol cans had been around for years, no one ever thought to fill the can with paint. In 1947, suburban Chicago resident Edward Seymour, at the suggestion of his wife, Bonnie, filled an aerosol can with aluminum-colored paint and pressed the button. The result was not only a smooth, evenly-coated painted surface, Seymour realized that he had now made painting easier and portable. Spray paint was an instant commercial success. In 1992, the Chicago City Council banned the sale of spray paint in an effort to crack down on graffiti.

Sleeping Cars on Trains

After a long, restless night on a train in 1862, George Pullman, a Chicago mechanical engineer, had the idea to create a luxury sleeping car for trains. The “Pioneer,” as he called it, had rubberized springs that reduced shaking, its walls consisted of dark walnut and the seats were covered with plush velvet. Silk window shades, crystal chandeliers and brass fixtures added to the overall feeling of luxury. At night, the seats unfolded into lower sleeping berths and an upper berth dropped down from a cabinet in the ceiling. To mass produce the railcars, Pullman created the Pullman Palace Car Company (on Chicago’s far South Side), which was responsible for other rail innovations like the dining car, the lounge car and the covered vestibule between passenger rail cars.

Car Radio

The first commercially successful car radio was designed and built in 1930 by Chicago’s Galvin Manufacturing Company. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Paul Galvin noticed that radios sales were down but car sales remained steady— owning a vehicle was still important to consumers, even in a poor economy. Galvin found a way to mount a radio in his Studebaker and drove it 815 miles to Atlantic City where the 1930 Radio Manufacturers Association Convention was being held. Upon arrival, he parked the car at the base of the pier and turned up the volume. The radio was a big hit, so Galvin returned to Chicago to begin manufacturing his product. On the way home he decided to give his product and company a new name — Motorola — a combination of “motor car” and “Victrola.”

Automatic Dishwasher

Automatic Dishwasher

Josephine Garis Cochran did not like having to hand wash dishes after entertaining friends and relatives at her home. She is claimed to have said, “If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself.” She partnered with a mechanic, George Butters, and created a machine that she showed at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago (1893). In addition to winning an award for its mechanical prowess and durability, it attracted considerable interest from restaurants and hotels, both of which saw the machine as a great way to become more efficient. Cochran’s Crescent Washing Machine Company became part of KitchenAid in 1913 through an acquisition by Hobart Manufacturing Company.

Soap Opera

After working as a staff writer at WGN in Chicago, former teacher Irna Phillips created a serialized daily program geared toward women, “Painted Dreams,” which was about a widowed matriarch of a large Irish-American family. The year was 1930, the medium was radio and the program aired for two years on WGN. Because her show often was sponsored by soap manufacturers, it became known as a soap opera. Prolific in her writing, Phillips also created other soap operas that aired on radio and television, including “Guiding Light,” “As the World Turns,” “Another World” and “Love is a Many Splendored Thing.”

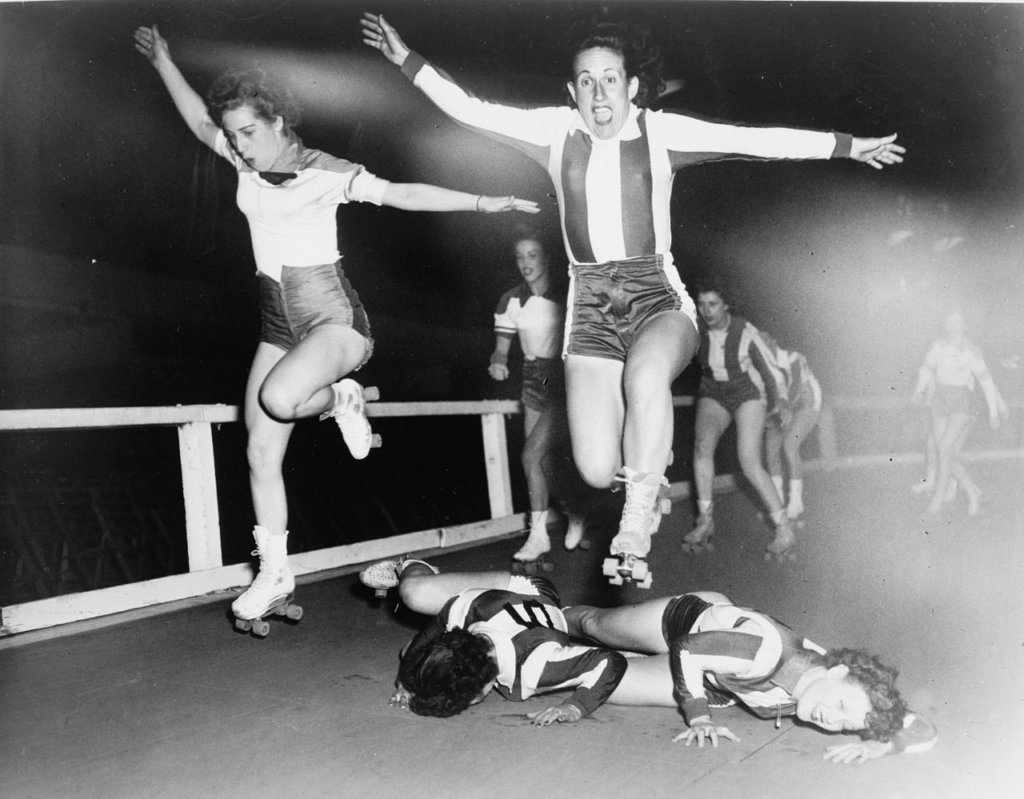

Roller Derby

Though roller skates were first introduced in London in 1735, the sport of Roller Derby was invented in 1935 by a Chicagoan, Leo Seltzer, an entrepreneur who was responsible for booking events at the old Chicago Coliseum just south of the Loop. For two years, the Coliseum hosted the “Transcontinental Roller Derby,” a multi-week event in which teams of skaters raced against one another on “trips” (miles that were tracked and plotted daily on maps) between large American cities, like Chicago to San Diego or New York to Salt Lake City. In 1937, Seltzer changed the rules to make the sport more exciting. Instead of long-distance races, teams scored points by breaking through and passing players on the opposing team. At 10 cents per ticket, Roller Derby was by far the cheapest sports ticket in town, an important consideration for those looking for an escape from the hardships of the Great Depression and a main driver of the sport’s rapid growth.

Vacuum Cleaner

Although a carpet-sweeping device was introduced a few years earlier, the first manually-powered vacuum cleaner was invented in 1869 by Chicago inventor Ives W. McGaffey. Though it required a certain amount of athleticism to operate (you had to turn a hand crank while pushing the device across the floor), the machines were commercially successful and sold for $25 apiece. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed McGaffey’s inventory, however, one of his original models currently resides at the Hoover Historical Center in North Canton, Ohio.

Farm Silo

In ancient Greece, farmers stored grain in huge pits in the ground. In fact, the word silo is derived from Greek meaning, “pit for holding grain.” In 1873, Fred Hatch of McHenry County, Illinois thought there had to be a better way. He built an above-ground “pit” with round walls made of wood — a structure that generally is acknowledged as the first modern silo. It was successful, too. The new silo on his farm was filled with green corn fodder, so much so that Hatch’s cows stayed fatter and gave more milk than they ever had before.

Chicken Vesuvio

No one is quite sure about the origin of this popular dish but many have suggested that it first appeared on the menu of Vesuvio Restaurant, 15 E. Wacker Drive, Chicago, in the early 1930s. Served with potato wedges, this dish features a half chicken that is sautéed with garlic, oregano, white wine, lemon juice and olive oil. Though the restaurant has long since faded into the darkness, the recipe lives on in a number of Italian restaurants throughout the Chicago area.

Mobile Phone

Building on his company’s earlier success with the car radio, color television and two-way walkie-talkies, Martin Cooper, an engineer at Motorola, produced the world’s first handheld mobile phone in April 1973 in Schaumburg, Illinois. In 1983, the company launched its first retail mobile phone — the DynaTAC 8,000X. The handset (a phone only, not a smartphone!) offered 30 minutes of talk time, six hours of standby and could store 30 phone numbers. Its price, $3,995, was a little prohibitive by today’s standards.

The Wienermobile

In 1936, when Oscar Mayer Company was headquartered in Chicago, Carl Mayer, nephew of company founder Oscar, had an idea — a 13-foot-long hotdog mounted on a car that would travel the streets of Chicago promoting the company’s iconic brand. General Body Company of Chicago designed the first Wienermobile, which featured open cockpits in the center and rear of the vehicle. Today, a number of vehicles comprise the Wienermobile “fleet,” all of which can serve fully prepared Oscar Mayer hotdogs on location. The fleet consists of the full-size Wienermobile, a Mini Wienermobile (a hotdog on the body of a Mini Cooper), a motorcycle with a hot dog sidecar, and the Wiener Rover and the Wiener Drone, two remote-controlled hotdog delivery vehicles.

Twinkies

Twinkies were invented in Schiller Park, Illinois on April 6, 1930 by James Dewar, a baker at Continental Baking Company. When Dewar saw machines used to make filling for strawberry shortcakes idled when strawberries were out of season, he came up with the idea to develop a snack cake filled with banana cream to increase the machines’ utilization. A co-worker called the product a “Twinkie” after having seen a nearby billboard advertising “Twinkle Toe Shoes.” When World War II caused bananas to be rationed, the company switched the filling to vanilla, which proved to be even more popular than the original.

Zipper

A Chicagoan, Whitcomb Judson, is generally credited with inventing the first clothing fastener in 1891. Used mainly on shoes and boots, the device utilized a chain-lock mechanism that held leather together without separating. In 1893, Judson exhibited his invention at the Chicago World’s Fair. The device enthralled fairgoers, leading him to launch the Universal Fastener Company in Chicago to manufacture his product. The chain-lock device never achieved commercial success, however, the clasping device was used by Judson and other inventors as a springboard to create new and improved fasteners that closely resemble the “zipper” that is commonly used today.

Interested in the World’s Fair of 1893? We recommend a classic Chicago tale, The Devil in the White City. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Seven Weird Chicago Laws That Are Truly Unique

If you Google “weird Chicago laws,” you’ll get a number of hits that list blue laws that were enacted in another era — laws that were designed to restrict certain activities on Sundays for religious reasons, such as gambling or the sale or consumption of alcohol.

Some of the weird Chicago laws that are still on the books border on the bizarre: it is illegal for a Chicagoan to dine in a restaurant that is on fire; it’s illegal for dogs to drink whiskey; it’s illegal for your pet to have poor hygiene; you might be picked up as a vagrant if you have less than $1 on you.

While strange laws aren’t unique to Chicago — many U.S. cities still have them on the books — our Town has always taken a certain amount of pride in doing things differently than other U.S. cities. From innovative legislation to bold new ideas, Chicago has always done things its own way — right or wrong.

Check out our list of weird Chicago laws:

- Can’t buy a car on a Sunday

- The movies you used to watch were censored

- Later Saturday night tavern hours

- No meat after 6 p.m. or on weekends

- Lack of food trucks

- The evils of Foie Gras

- No pick-up trucks on Lake Shore Drive

Can’t Buy a Car on a Sunday

In 1984, at the behest of the Chicago Automobile Trade Association, the Illinois legislature passed a weird Chicago law that forbade auto dealers in the state from opening for business on Sundays. Why? The dealers say they wanted a day for their employees to be with families and not have to worry about stolen sales from other dealers that decided to stay open on that day. The ban on car sales on Sundays is still in effect throughout Illinois. Because many other retailers are now open seven days a week, one can only wonder why auto dealers need to be singularly protected.

The Movies You Watched Were Censored

From 1907-1984, every movie that played in a Chicago movie theatre had to receive an “OK” from the Chicago Film Review Board. The Film Review Board was operated by the Chicago Police Department and its board members generally consisted of widows and orphans of Chicago police officers. Sometimes the Board recommended edits to films, sometimes films were banned entirely, like the original version of “Scarface.” It opened in theaters nationwide in early 1932 but didn’t play in a Chicago theatre until late in 1942. It seems the film Board didn’t like the way Chicago was portrayed. The Board was disbanded in 1984 because it had become irrelevant in the face of rigorous film industry self-regulation (a rating system).

Small movie theater

Later Saturday Night Tavern Hours

Except for gambling towns like Las Vegas and Atlantic City where casinos serve alcohol 24 hours a day, Chicago has the latest Saturday night closing time for a tavern — 5 a.m. — than any other city in the nation. (Many cities match Chicago’s 4 a.m. closing time during the week, however.) Approximately 150 taverns in Chicago have 4 a.m./5 a.m. liquor licenses, a number that has held steady for the past few decades.

No Meat After 6 p.m. or on Weekends

Between 1952 and 1977, the sale of meat was banned at supermarkets throughout the Chicago metropolitan area after 6 p.m. on weekdays and all day on Saturdays and Sundays. To ensure that customers didn’t try to purchase product, retailers threw a tarp over the meat case; customers who wanted to enjoy a barbecue over the weekend had to remember to “stock up” during the week or go without. Why the weird Chicago law? The local Meat Cutters union wielded enormous power over the local retailers with their labor contracts — and the Meat Cutters didn’t want their butchers working late hours or on weekends when they could (in theory) be home with their families. Eventually, the ban was lifted when the union realized that its members’ jobs were in jeopardy if the store couldn’t sell meat products during the store’s business hours.

Lack of Food Trucks

The City of Chicago has long had a love/hate relationship with street food vendors — both of the Daley mayoral administrations (1955-1976 and 1989-2011) made it difficult for operators of food carts to peddle their wares on street corners or at public events. When food trucks became all the rage in New York and Los Angeles in 2010, Chicago again took a cautious approach toward licensing them. Initially, the city didn’t allow any food preparation on board the trucks, only products that had been prepared and packed in a commercial kitchen were allowed. Two years later, the city relented on the preparation rule but then issued an edict that no truck could locate within 200 feet of an existing brick and mortar restaurant and when they did park it was for a limited time. Why? The city wanted to protect the turf of existing restaurants, not wanting upstart food trucks to steal their business. Today there has been an accommodation of sorts — the city limits the number of food truck licenses but lets them park in pre-established zones throughout the city.

The Evils of Foie Gras

In April, 2006, the Chicago City Council barred restaurants from serving foie gras — fatty duck or goose liver — because the animals were mistreated and abused while they were being raised. The City became a laughing stock worldwide and a displeased Mayor Richard M. Daley called it ‘the silliest law they’ve (the Council) ever passed.” Thanks to intense lobbying by the restaurant industry, the ban was overturned two years later and customers were once again allowed to consume the gastronomic delight. Interestingly, New York City recently approved legislation that will ban foie gras in restaurants beginning in 2022. Who’s the laughing stock now?

No Pick-Up Trucks on Lake Shore Drive

Before automobiles, the city had a number of ordinances prohibiting certain activities near the lakefront. One of them banned commercial vehicles (anything that carried freight) from using streets adjacent to the lake, such as Lake Shore Drive. In 2020, the ban on trucks is still in effect for Lake Shore Drive and, yes, that includes pick-up trucks — even those that are not carrying freight or those that are not even considered to be commercial. Although this weird Chicago law isn’t closely monitored, Chicago Police still issue citations whenever they see pickups headed down the Drive and unknowing drivers are shocked to learn that they have broken a weird Chicago law that no one knows exists.

If you want to learn some more interesting facts and stories about Chicago, consider taking a Chicago city tour with L Stop Tours!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

Speak Like a Local — 17 Street Names Pronounced the Chicago Way

Long before the existence of cell phones, the Internet or even an on-board public address system, Chicago’s suburban commuter railroads used a decidedly low-tech way of announcing each train’s next stop. Conductors walked through every car and, in their own inimitable style, bellowed out towns and Chicago street names that didn’t sound like any that I knew. “Next stop…BROOT’-feel. BROOT’-feel is next” (instead of Brookfield). Or “We’re coming up on LAV’-earn Avenue” instead of the correct pronunciation — Luh-VERN’ (accent on the second syllable). And that was just on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Line.

Other locations throughout the metropolitan area were often mispronounced by folks, as well. Soldier Field often became Soldiers Field, Comiskey Park became Cominskey Park and the name of our state often became ILLI’-noise instead of Ill-ANNOY’.”

Does it matter if a person mispronounces the Chicago street names and other locations throughout the area? Usually, no. Most people understand what you’re referring to and nod accordingly for clarity. Occasionally, however, mispronouncing some Chicago street names can be downright embarrassing — it clearly marks you as a rube from out of town, perhaps someone that can be taken advantage of.

A much better solution is to learn to pronounce Chicago street names and other important locations the way Chicagoans pronounce them — and sound like a local. That way you’ll look and sound like you fit in. To help you in this noble quest, we have prepared a Chicago street name pronunciation guide to assist you in your travels throughout the metropolitan area.

For those of you that are more verbal learners over readers, consider taking one of our Chicago city tours, and we’ll teach how to pronounce dozen of Chicago street names.

1. Armitage Ave.

The Chicago pronunciation of this North Side thoroughfare is AR’-mi-tidge, not AR’-mi-taj’. This slight mispronunciation not only gives the street a “Chicago” sound, it makes the French cringe, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

2. Berenice Ave.

If you don’t look carefully at the spelling of this North Side Chicago street name, you’re likely to say Burr-NIECE’. But that’s wrong, the correct pronunciation is BARE’-uh-niece.

3. Bryn Mawr Ave.

This North Side Chicago street name that cuts through the Edgewater neighborhood is named after a railroad stop near Philadelphia. To pronounce it correctly, ignore the “y” and the “w” and say BRIN’-mar.

4. Clybourn Ave.

Archibald Clybourn built the city’s first slaughtering plant in the early 1800s and out of towners have been butchering the pronunciation of his last name ever since. It’s CLY’-born, not CLEE’-burn.

5. Cuyler Ave.

Edward Cuyler built a railroad between Chicago and Janesville, Wis. and for this accomplishment had a street named after him. In Chicago, we pronounce it KAI’-ler.

6. Desplaines St.

The name is derived from plane trees in the area that French explorers thought resembled a similar species in Europe. Like most French-origin words that have found their way into the local vernacular, Chicagoans prefer to pronounce it without any silent letters and say it exactly the way it is spelled, Des-PLANES’. The same is true for the suburb, Des Plaines, which is just north of O’Hare and which also has a lot of planes.

7. Devon Ave.

Originally known as Church Road, it was changed to Devon in the 1880s by a developer who named it after Devon Station on the Main Line north of Philadelphia. Never say DEV’-in, the correct pronunciation is De-VAUGHN’.

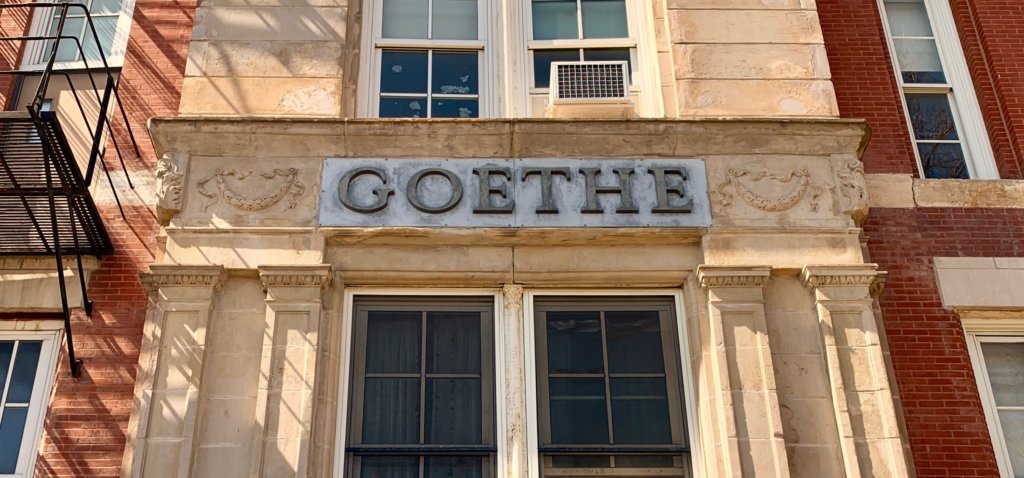

8. Goethe St.

German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s last name is pronounced GUR’-tuh, but not in Chicago. We defiantly say GO’-thee and, are proud of it.

9. Honore St.

Henry Hamilton Honore was a real estate magnate successful enough to have this West Side street named after him. It’s not Hoe-NORE’, locals pronounce it HONOR’-ray.

10. Leavitt St.

A north-south Chicago street name on the West Side of the city, Leavitt looks as though it should be pronounced LEAVE’-it, but it isn’t. The correct local pronunciation is LEV’-it. Take it or leave it.

11. Melvina Ave.

Named after a Wisconsin summer resort, the Chicago street name is pronounced with a long “i” sound, as in Mel-VINE’-uh, where nothing could be fine-uh.

12. Nina Ave.

The history books say this street was named after one of Christopher Columbus’ boats, but Chicagoans pronounce it differently than Columbus did. For some odd reason, we say NINE’-uh, not NEEN’-uh.

13. Paulina Ave.

The wife of an early Chicago real estate developer, locals pronounce this Chicago street name Paw-LINE’-uh, not Paw-LEEN’-uh. Take that, Ms. Porizkova!

14. Racine Ave.

This one is not definitive — it’s split about 50/50. South Siders tend to say RAY’-seen and North Siders say Ruh-SEEN’. In France (Racine is a French name), they say RAH’-seen. Go figure.

15. Throop St.

Amos G. Throop, a Chicago real estate developer, pronounced his surname TROOP, totally ignoring the “h.” Chicagoans believe that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery and do the same.

16. Vincennes Ave.

Named after an explorer, the French pronounce it Vaugh-SEN’. In Chicago, no one knows what you’re talking about when you say it this way. Butcher it like the rest of us and say Vin-SENZ’.

17. Wabansia Ave.

There are many ways to say it wrong, only one way to say it like a local. It’s Wuh-BAHN’-see-uh.

If you want to learn more facts about Chicago that will make you seem like a local, consider going on one of our Chicago city tours. All of our guides are native to Chicago and love to answer any and all questions you have about the city! We hope to see you soon.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

When it gets dark on April Fools Day, you can see them gathering at various points along the lakefront.

They’re well-prepared for a long evening — Coleman lanterns, barbecue grills, charcoal, portable televisions, lawn chairs and ice chests full of beer. Rain gear is vogue if the sky shows even the slightest hint of foul weather; playing cards and poker chips are on hand in case there isn’t much action during the evening.

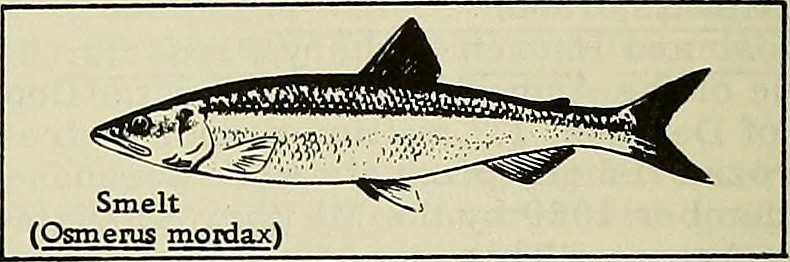

These are Chicago’s hardy smelt fishermen, a group of enthusiastic anglers who brave frigid weather, ungodly fishing hours and boredom in order to capture a much-prized seasonal favorite — the elusive smelt — a short, 4-6 inch fish that spawns along the shoreline of Lake Michigan for six weeks every spring.

The Chicago File, April 1991

When I wrote the above article 29 years ago in The Chicago File, fishing for smelt along Chicago’s lakefront during the month of April was an extremely popular activity. It was highly promoted by the Chicago Park District as a unique seasonal outdoor activity and, as a result, fishermen from all over the Midwest came to Chicago to spend an evening or two on the lakefront capturing the much sought-after fish.

Why was smelt fishing so popular?

Much of the appeal of smelt fishing stemmed from the fact that it was a highly unique fishing experience, it was radically different than other forms of the sport. Smelt fishing, for example, had always been a nighttime activity — in Chicago it was (and still is) permitted only during the month of April between the hours of 7 p.m. and 1 a.m. In other words, it’s the perfect sport for night owls and insomniacs.

Smelt fishing required special equipment in order to be successful. To catch smelt you used seine, dip or gill nets of a certain size – they could not exceed 12 feet in length or six feet in depth. The mesh size of the net could be no larger than one and a half inches. The netting restrictions were crafted and enforced by the Chicago Park District and were designed to ensure that no fishermen took more than their fair share of smelt from the water during any given net hoist.

Another aspect of smelt fishing that made the sport unique was the somewhat odd local tradition in which fishermen felt it necessary to prepare, cook and consume the fish within minutes of it being caught. This is where the grill, charcoal, ice chests of beer and cooking oil they dragged to the beach came in. All of these items were necessary in order to have a proper “smelt fry” on an otherwise deserted Chicago beach in the middle of the night.

So, yes, for more than a century, the unique sport of smelt fishing has been a popular Chicago outdoor sports activity. And to this day, there are plenty of smelt fishermen who eagerly await the arrival of April 1 so they can head out to the lakefront and net themselves some smelt. The only problem is that now, Chicago has more smelt fishermen than there are likely smelt in Lake Michigan.

What happened to the smelt?

Ecologists point to several changes in Lake Michigan that have caused the smelt population to dwindle over the years. Coho Salmon, for example, have now become predators of smelt because other fish they used to consume (like lake herring) have vanished completely from the lake. Another reason there are so few smelt in the lake is because of the rapidly multiplying population of invasive zebra mussels in the lake. Because zebra mussels are relatively new to Lake Michigan and because they compete with fish for lake plankton (food), there is less food available for consumption. As a result, the smelt get less plankton and many do not survive.

Ecologists point to several changes in Lake Michigan that have caused the smelt population to dwindle over the years. Coho Salmon, for example, have now become predators of smelt because other fish they used to consume (like lake herring) have vanished completely from the lake. Another reason there are so few smelt in the lake is because of the rapidly multiplying population of invasive zebra mussels in the lake. Because zebra mussels are relatively new to Lake Michigan and because they compete with fish for lake plankton (food), there is less food available for consumption. As a result, the smelt get less plankton and many do not survive.

The decline of smelt in Lake Michigan has also caused many smelt fishing festivals and lakeside cookouts to be canceled, as well. North suburban Lake Forest recently canceled Smelt-O-Rama, a long-standing event on the lakefront that taught youngsters how to catch, clean and cook the tasty little delicacies. Similarly, the Park District of Highland Park canceled its long-running Smelt Fest because there simply weren’t enough fish being caught to make it viable.

According to the Chicago Park District, smelt season will again open on April 1 and will run through the end of the month — with the same fishing hours, the same net restrictions and the same rules about netting too many fish, although this really hasn’t been an issue for the several years.

So, what do you do if you crave smelt and want to down a few this evening?

The best advice? Let someone else find it and net it.

One of my favorite seafood joints on the South Side, Calumet Fisheries, still has smelt on their a la carte menu in half- and full-order portions. I suspect, however, that the fish come from Lake Erie or somewhere else where they are in greater supply.

Sound fishy?

Enjoy.

If you want to learn more about Chicago’s history, and the events and people that made the city what it is today, consider going on a Chicago tour with L Stop Tours. Book a unique neighborhood tour today!

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.

– By Tom Schaffner

The invention of baseball is murky. Was it created by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, New York, or, was it Alexander Cartwright, a volunteer firefighter and bank clerk in New York City who codified a set of rules that would form the basis for modern baseball? Adding to the controversy is evidence that early forms of baseball were played in the years just following the American Revolution, several decades before Doubleday or Cartwright were even on the scene.

But Who Invented Softball?

There is no debate about who invented softball, however. The game was invented in 1887 on Thanksgiving Day in Chicago.

How it all Started

The story of its invention is compelling. A group of men gathered at Chicago’s Farragut Boat Club to learn the result of that day’s Harvard versus Yale college football game. When Yale was announced as the winner, a Yale alumnus wadded up a boxing glove with the string ties and playfully threw it at a Harvard supporter. The Harvard supporter swung at the glove with a broom handle and the rest of the group looked on with interest. George Hancock, a reporter for the Chicago Board of Trade jokingly called out, “Play ball,” and the first game of “softball” began in earnest. According to reports, 80 runs were scored during that initial match and the final score was 41-40.

Yellow softball on pitchers mound

By 1895, the game had moved outdoors, a complete rulebook had been issued and players had developed new names for the sport — “kitten ball,” “diamond ball,” “mush ball,” and “pumpkin ball.” It wasn’t until 1926 that the term softball was first used. Prior to this date, the size of the ball had varied considerably, depending mainly on where the game was played. Most of the world adopted a 12-inch ball and played the game with gloves. In Chicago, where the sport was born, the game moved forward with a 16-inch ball — and no gloves were allowed. The reason for the popularity of the sport in Chicago was because a bigger, softer ball meant that it could be played on smaller city “fields,” such as a cramped playground, someone’s back yard and even inside a gymnasium, if necessary.

The 16-inch game became incredibly popular nationwide when the first-ever national amateur softball tournament was held in conjunction with Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933.

The Strategy of Softball

In addition to no playing with gloves, the 16-inch game is different from other versions of softball in several respects. As the game progresses, the 16-inch ball gets softer, making it more difficult to hit great distances. Teams and batters must alter their offensive strategies as the game moves into the late innings. Throwing and catching the ball also requires players to utilize different techniques. Fielders will often bounce the ball to their throwing target to make it easier to complete the play. Others who are looking to catch the ball will often let the ball hit their chest first before trapping the ball with their hands and fingers.

Like golf, the sport of softball has seen a precipitous decline in participation during the last several decades. Youth have gravitated to other sports and Baby Boomers — one-time stalwarts of the sport — are aging and playing less. And while it is rare indeed to see a pick-up softball game being played in fields or open spaces around the city (as there used to be), there are still a number of city and suburban leagues where those who are interested can get involved.

So whether you play 12-inch, 16-inch or women’s fast pitch, remember that the game was invented here by a group of football fans who improvised a “ball” with a boxing glove.

Only in Chicago.

If you thought Chicago’s history with softball is interesting, then considering booking one of L Stop’s Chicago tours. Our tours are filled with interesting Chicago history facts that you won’t get from other tours.

Holder of two journalism degrees, including a masters from Northwestern University, Tom Schaffner is a native of the Chicago area and has spent nearly 50 years as a writer, editor, publisher and professional communications consultant. He was also the founder, editor, and publisher of the Chicago File, a newsletter for former Chicagoans. Tom is also the co-owner of L Stop Tours.